05/01/2017

The main purpose of a score on any type of assessment is to convey information about students’ performance. Educators, parents, and students all want to know whether a student’s score represents a strong performance or is cause for concern.

But, in order to evaluate a score, we need a frame of reference. Where do educators find this basis for comparison? This is where test norms come in.

In this blog, we’ll review how test norms are developed and—more importantly—how they can assist teachers with instructional decision making.

What are test norms?

Test norms—also known as normative scores—are scores collected from a large number of students with diverse backgrounds. The purpose of test norms is to identify what “normal” performance might look like on a specific assessment.

As a society, we have a tendency to characterize all measurable traits normatively, which is why normative scores can be so useful for describing academic performance.

So, how is a “normal” performance determined?

Normal performance refers to what scores are typically observed on an assessment by students in different grades. For example, students in grade 1 are not expected to know as much as students in grade 6. If students in all grade levels completed the same test, the younger grade students would be expected to obtain a lower score than the older grade students. In other words, the score distribution would be considered “normal” in relation to student grade levels.

Test scores don’t just vary from grade to grade, however. Typically, test scores will also vary among students in the same grade because of differences in their prior learning and general abilities.

Unlike benchmarks, test norms provide information related to all students’ current skills, whereas benchmarks determine which students have met a single specific goal.

How are test norms developed?

Test norms can only be developed for standardized tests—that is, tests that have specific directions for administration that are used in the same way every time the test is given. Educators can only compare scores when the test is identical for all students who take it, including both the items and the instructions.

Comparing scores from tests with different items and directions is not helpful for determining test norms, because students did not complete the same tasks. This means that score differences could vary due to the different questions on the tests.

To create standardized tests and to understand the differences in students’ scores within and between grade levels, test developers must create and try out items many times before they come up with a final test.

Once the test is complete, the test developers give the test to a “normative sample” that includes a selection of students from all grades and locations where the final test will be used. This sample is designed to allow a collection of scores from a smaller number of students than the entire group who will eventually take the test.

The normative sample group must be picked carefully, however. It needs to be diverse and representative of all the grade levels and students who will take the test later on. To ensure a representative normative sample, a certain number of students from each grade and from applicable geographic regions should be selected, as well as students with different background features.

For example, when choosing a normative sample for a state assessment, the test developer should include:

- A set number of students from each grade level

- Students from each county or school district in the state

- Students with disabilities

- Students who are learning English

- Students from different socioeconomic backgrounds

To determine how many students should be chosen for a normative sample, test publishers typically use data from the US Census Bureau. Using the information that the government collects about people in the country, publishers assess students of various backgrounds who attend schools in different states and regions.

Once the normative sample is selected, the students complete the assessment according to the standardized rules. The scores are then organized by grade level and rank ordered—that is, they’re listed from lowest to highest. These are then converted to percentile rankings and analyzed.

Using percentiles to represent test norms

The measurement of student performance begins as a raw score, such as the total number of correct responses. This score then needs to be translated into a scale that indexes what is typical. Using a percentile rank for this scale is both convenient and readily understood.

How does this work?

A percentile represents the score’s rank as a percentage of the group or population at or below that score. For example, if we say that a score of 100 is at the 70th national percentile, that means 70% of the national population scored at or below 100.

Percentiles generally range from 1–99, with the average or typical performance extending from about the 25th to the 75th percentile. Scores below the 25th percentile are below average, while scores above the 75th percentile are considered above average.

Insights to move learning forward

Discover valid and reliable assessments from Renaissance for pre-K–grade 12 learners.

How do test norms assist teachers in education?

As mentioned earlier, scores collected as part of a normative sample offer a way for educators to know which scores are typical and which ones are not. To determine if a particular student’s score is typical, the teacher must compare the score to the available test norms.

For example, if a teacher wants to know if a score of 52 is within the average range on a standardized test, she can consult the norms for that test. If the test has a range of scores from 0 through 100 and the average score is 50, then 52 would be considered normal. But if the test has a range of scores from 0 through 200 and the average score is 100, then 52 would be considered a lower-than-average score.

With this example, the teacher could then look and see the percentile ranking for a score of 52, which would indicate what percentage of students in the normative sample scored below and above 52.

This information would help the teacher to know how far below average the student’s score is and to then identify how many points the student would need to gain to reach the average range of scores.

Once this information is collected and analyzed for all of the teacher’s students, she can develop instruction that matches each student’s learning needs.

It’s important to mention that test norms can be used to identify both lower-achieving and higher-achieving students, and that teachers should develop lessons that help both groups of students to achieve learning goals.

Test norms and benchmarks: Frequently asked questions

Now let’s dive into some frequently asked educator questions about test norms and benchmarks, specifically as they relate to assessments and reports in FastBridge. These questions include:

- Are norms and benchmarks truly different? How so?

- Why do they tell me different things?

- Which one is recommended by Renaissance?

#1: What is the difference between a test norm and a benchmark?

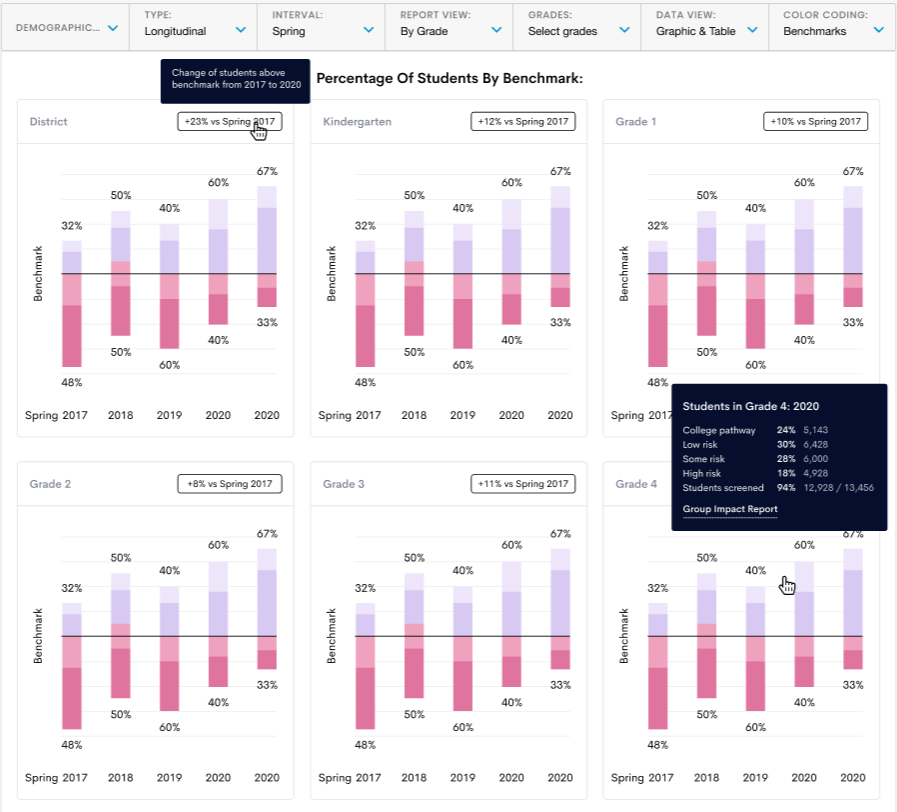

Although many FastBridge screening reports display both test norms and benchmarks to support decision making, they are fundamentally different.

A normative comparison allows you to compare a student’s score to their peers. For example, when driving, the flow of traffic is a normative comparison. Depending on the location and time of day, the flow of traffic can change, given the other drivers on the road.

FastBridge has both local and nationally representative norms, which allows you to compare students’ scores to both local peers and to students nationwide.

Benchmarks, however, support the comparison of norms to a predetermined criterion. Using the driving example above, the speed limit would be an example of a benchmark. It doesn’t change based on who is driving on a given road. Instead, it provides a constant comparison to determine if your speed is safe in the given setting.

#2: Why do test norms and benchmarks tell me different things?

To answer this question, let’s stick with the driving example from above:

If we compare my speed of 60 mph to a speed limit of 55 mph, we might determine that I am driving too fast. However, if we compare it to the fact that all other drivers on the road are passing me and driving faster than 60 mph, we might decide that I’m driving too slowly.

The comparison we make might lead to different decisions. A police officer may be more attuned to the criterion—in this case, the speed limit of 55 mph—while a passenger in the car may pay more attention to the flow of traffic, or norm.

Similarly, when comparing screening data to norms or benchmarks, you might see some different patterns. For instance, if your school has many high-performing students, you may have students whose scores are low when compared to local test norms.

Those same students’ scores may meet low-risk benchmarks, though, and be within the average normative range nationally.

#3: Does Renaissance recommend using test norms or benchmarks?

This depends on the question you’re asking and the decision you’re trying to make.

Test norms are best used when decisions are being made that require you to compare students’ scores to that of other students. In other words, how is this student performing in relation to peers? At Renaissance, we recommend using test norms to decide whether additional support needs to be supplemental (i.e., provided to a few students) or provided to all students through Tier 1 core instruction.

On the other hand, when you want to determine if a student is at risk of not meeting standards, benchmarks should be used. At Renaissance, we recommend using benchmarks to determine which students need additional support, given that they’re not currently meeting grade-level expectations.

#4: How were normative ranges set?

The normative ranges were set to show where most students’ scores fall, and the ranges align with typical resource allocation in schools. Most schools do not have the resources to provide supplemental intervention to more than 20–30% of students.

FastBridge norms make it clear which students fall in these ranges. Additionally, if a student’s score falls between the 30th and 85th percentile ranks, the score is consistent with where the majority of students are scoring. That range also includes students who are likely receiving core instruction alone.

Remember, norms are not able to be used to indicate the risk of poor reading or math outcomes. So, students whose FastBridge CBMreading score is at the 35th percentile may be at-risk in reading, even though they likely will not receive additional support outside of core instruction.

This is why Renaissance recommends using benchmarks in conjunction with test norms so that the best decisions can be made about how to meet each student’s needs.

For example, a core intervention might be appropriate if a large number of students score below the benchmark but are within the average range compared to local norms.

#5: Can we set custom benchmarks in FastBridge?

District Managers can set custom benchmarks in FastBridge. If your school has done an analysis to identify the scores associated with specific outcomes on your state tests, those custom benchmarks can be entered into the system.

You can utilize this FastBridge Help Article to learn how to set custom benchmarks.

#6: Why are local test norms missing from some of my reports?

Because test norms compare students’ scores to those of other students, those comparisons could be misleading if only a portion of a school or district is assessed.

For example, if we only screen students whom we have concerns about, a student’s score may look like it’s in the middle of the group when, in reality, the student is at risk of not meeting expectations in reading or math.

Because of this, FastBridge will only calculate and display local test norms when at least 70% of students in a group have taken the screening assessment. If you have fewer than 70% of students screened with a specific assessment, we recommend using national test norms or benchmarks to identify student risk levels.

#7: How are growth rates for goals and the Group Growth Report set?

The growth rates used in the FastBridge Progress Monitoring groups are based on research documenting typical improvement by students who participate in progress monitoring.

The growth rates in the Group Growth Report are based on the scores corresponding to the FastBridge benchmarks. However, they can be customized when accessing that report.

#8: How are rates of improvement (ROI) related to norms and benchmarks?

The rates of improvement (ROI), or growth rates, you’ll find in various parts of FastBridge are derived from our product’s normative data. The growth rates are developed based on the typical performance of students in the national test norms at every fifth percentile ranking.

You can find these growth rates in the normative tables in the Training and Resources tab within FastBridge. This section of the system also contains information about interpreting FastBridge norms and benchmarks.

Ultimately, while the two ideas have different applications, we know schools use test norms and benchmarks both together and separately to aid in decision making. Because of this, you can see both on many of our reports.

Utilize FastBridge’s valid and reliable assessments to determine test norms and provide intervention for students

Without an accurate way to determine whether scores are typical or average for students in a given grade, it’d be difficult for educators to provide the right intervention or instruction to students.

Test norms are scores from standardized tests given to a representative sample of students who will later take the same test to determine the range of all possible scores on that test for each grade level. The scores are then matched to percentile ranks.

With FastBridge, Renaissance provides a reliable and valid assessment tool using curriculum-based measures (CBMs) and computer-adaptive tests (CATs) to help determine students’ needs, align the right interventions, and monitor progress—all in one platform.

Learn more

Connect with an expert today to learn more about bringing FastBridge or other Renaissance solutions for reading, math, and social-emotional behavior (SEB) to your district.