February 8, 2018

This is the fourth entry in the Education Leader’s Guide to Reading Growth, a 7-part series examining the growth factors and growth predictors for boosting reading achievement.

You’ve set your students up for the reading success they need to be college- and career-ready graduates. At least 15 minutes of every school day are reserved for reading practice. Teachers have the tools needed to identify a student’s reading level and ZPD. Students have easy access to diverse fiction and nonfiction books. You’re recognizing and celebrating student effort.

But is it actually working?

It’s happened to all of us: After getting all the ingredients and following the recipe’s steps exactly, the meal just didn’t turn out as expected. But your students are infinitely more important than dinner, and you need to know that everything is working as expected now—you can’t wait until the end of the year to see if the recipe was a success or failure.

So how do we monitor reading growth without hours and hours of formal testing? How do we ensure students are truly on the path to achievement?

Research suggests there is a quick and easy way to do exactly that. A study of the reading habits of more than 2.2 million students using a research-based reading practice program revealed that literal comprehension can be used to predict reading gains. Students who averaged 75% or higher on the program’s short literal comprehension quizzes throughout the school year were found to have made accelerated, or higher-than-average, gains. The greatest gains were seen when students averaged 85% to 95% on quizzes. On the other hand, students with lower average scores in literal comprehension saw lower-than-average gains.1

To be clear, literal comprehension is not the end goal of reading instruction and practice, especially in the middle and upper grades. Inferential comprehension, evaluative comprehension, and other higher-order thinking skills are all critical for students to be successful in school and in life. However, these competencies cannot occur in the absence of literal comprehension—and they are often much more difficult and time-consuming to measure than literal comprehension.

High literal comprehension is the solid foundation students need to build higher-order skills. Low literal comprehension indicates that the fundamentals are missing and deeper comprehension cannot take place. This study found that literal comprehension was a meaningful predictor of overall reading achievement—and thus a very helpful way for educators to monitor students’ reading in the months or weeks between lengthier formal assessments.

Literal comprehension, ZPD, and growth

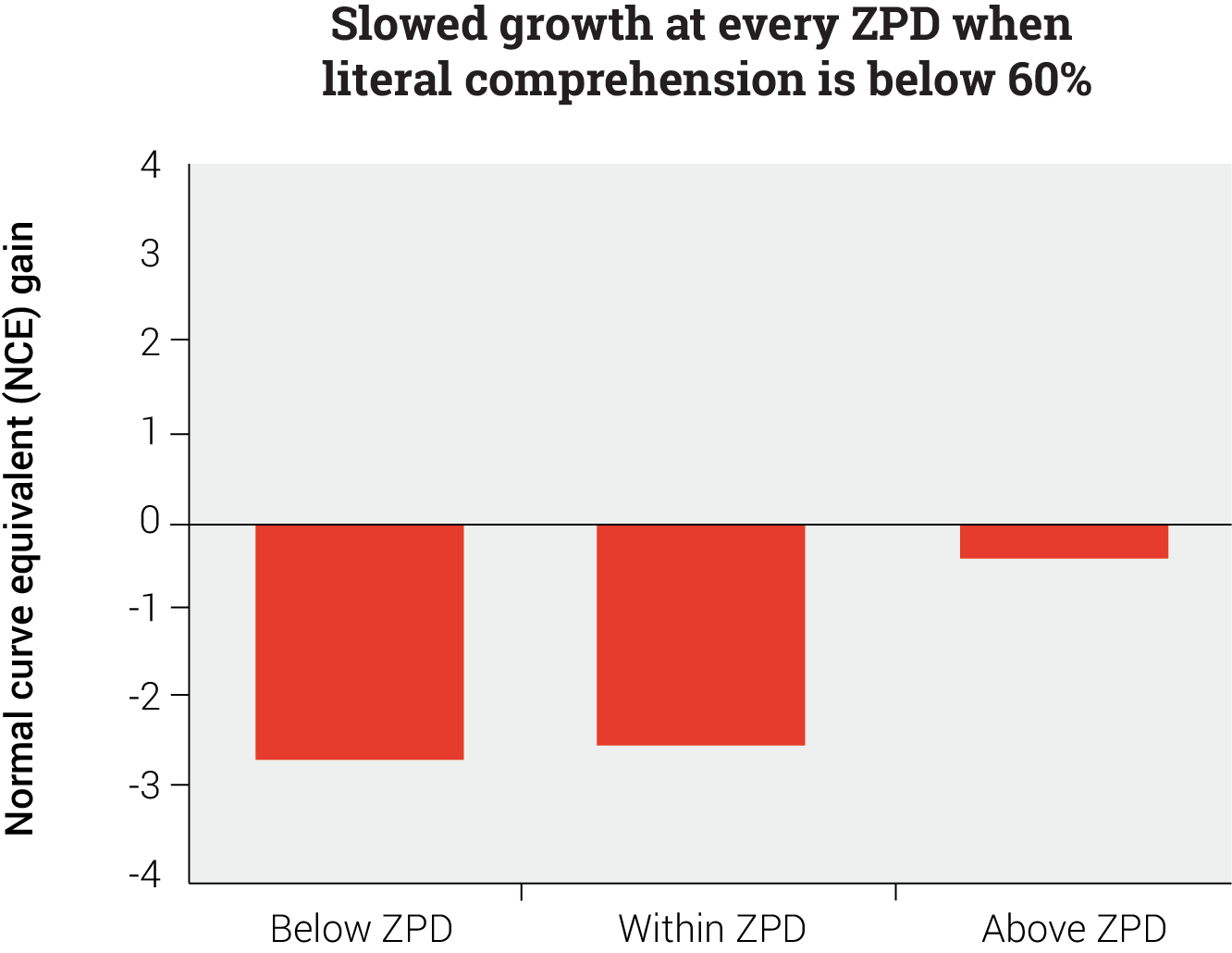

The same study also found that, when literal comprehension dips below 60%, reading growth slows regardless of whether a student is reading below, within, or above their Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD).

As discussed in the last blog post, lower literal comprehension scores may indicate a student did not actually read the text, did not put effort into understanding the text, chose or was assigned a text well above their skill level, needed more instruction and guidance around using comprehension strategies, or did not have the background knowledge or vocabulary needed to comprehend the text’s topic.

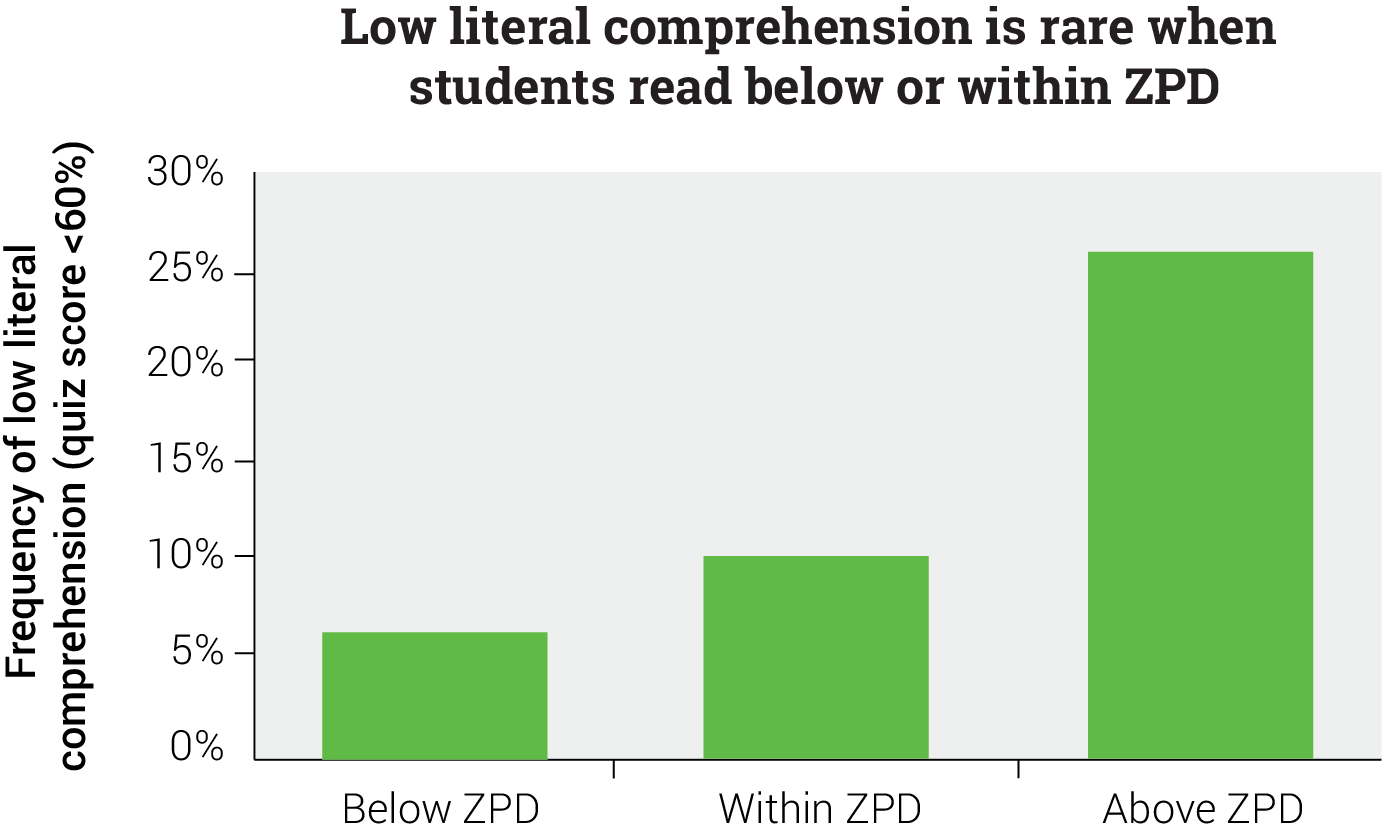

However, literal comprehension below 60% is quite rare when students read below or within their ZPD. Looking at more than 112 million quizzes, the study found that students scored below 60% on only 6% of quizzes when reading below their ZPD and on only 10% of quizzes when reading within their ZPD.

As a result, when it comes to texts within or below a student’s ZPD, teachers can use literal comprehension scores as a quick accountability check to ensure students are truly putting effort into their reading and not skimming or entirely skipping texts. If a student is putting forth effort, low average literal comprehension with these texts could be a “red flag” indicating that the student is struggling with a specific concept, idea, or vocabulary term, or that the student’s reading level has been misidentified and their ZPD set too high. In all cases, teachers should intervene—and the low score is the early “tip off” that empowers them to do so in a timely manner.

Low literal comprehension scores are more common when students read above their ZPD, with students scoring below 60% on more than a quarter of these quizzes. As noted in the last post, gains are not accelerated when students struggle to comprehend these harder texts; instead the reverse happens and gains decrease.

It may be that a low score on above-ZPD reading is less likely caused by a lack of effort—although that may still happen—and more likely a sign that a student simply needs greater scaffolding or support to engage with the more challenging reading material. Once again, teachers should intervene quickly and the low score is the signal they need in order to do so right away instead of after midyear screening.

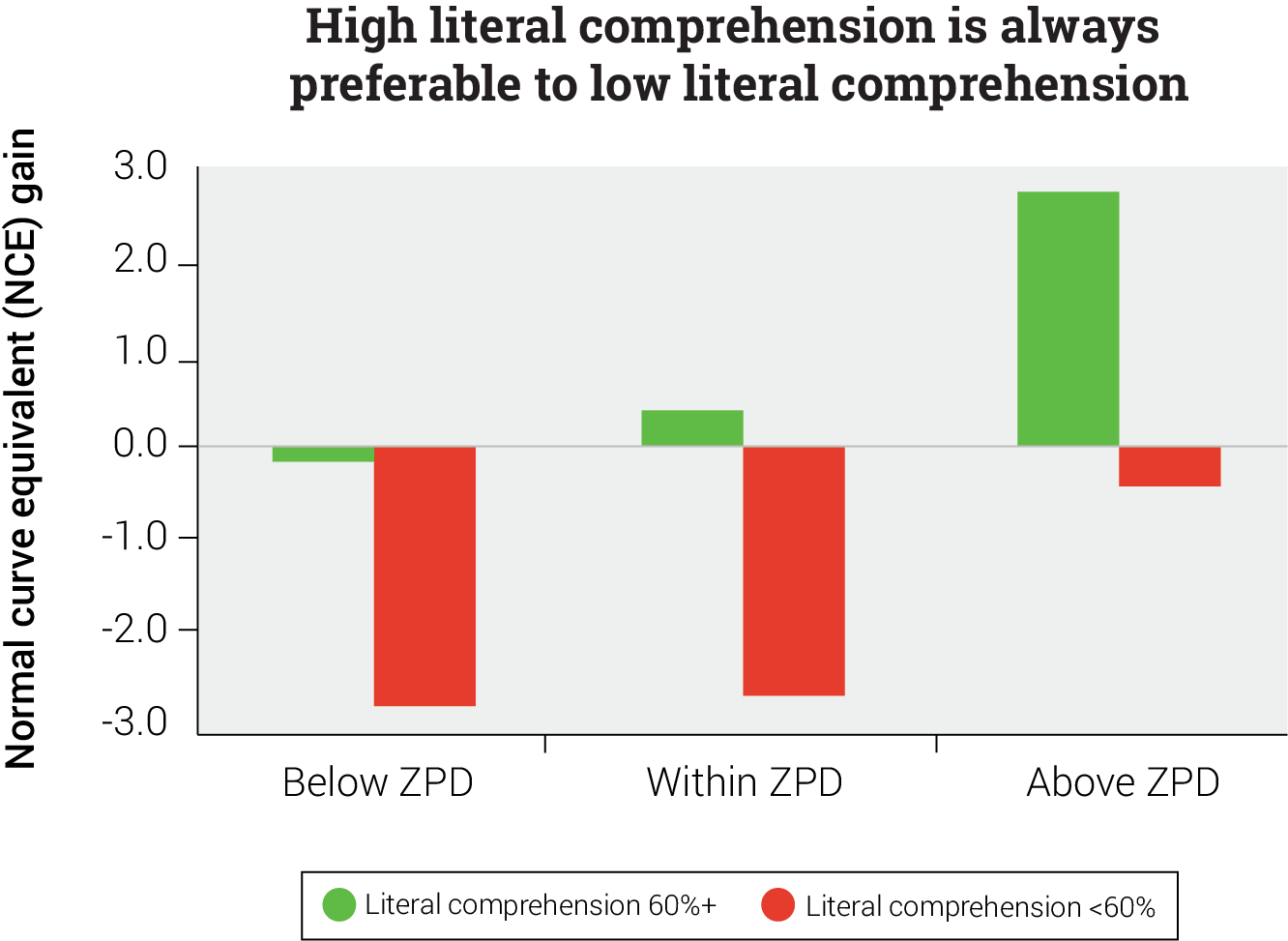

When we compare low literal comprehension to higher literal comprehension across all three ZPD levels—below, within, and above—we see accelerated gains occurred in only two scenarios: when comprehension was above 60% on within-ZPD and above-ZPD texts.

(The greatest growth occurs when students have higher comprehension on an above-ZPD text, but this is less likely to happen—as seen above—and above-ZPD reading may decrease motivation. For high growth and high motivation, we encourage educators to follow the ZPD “rules of thumb” from the last post where the majority of a student’s reading is within their ZPD.)

Literal comprehension, engaged reading time, and growth

Educators can also use literal comprehension to monitor the quality of reading time—helping to maximize the impact of every minute spent reading. Looking at a comparison of the reading time, literal comprehension, and reading growth of more than half a million students, we see that high literal comprehension is critical for getting the most growth out of each minute spent reading.1 Based on this data, we offer three main take-aways for the reader.

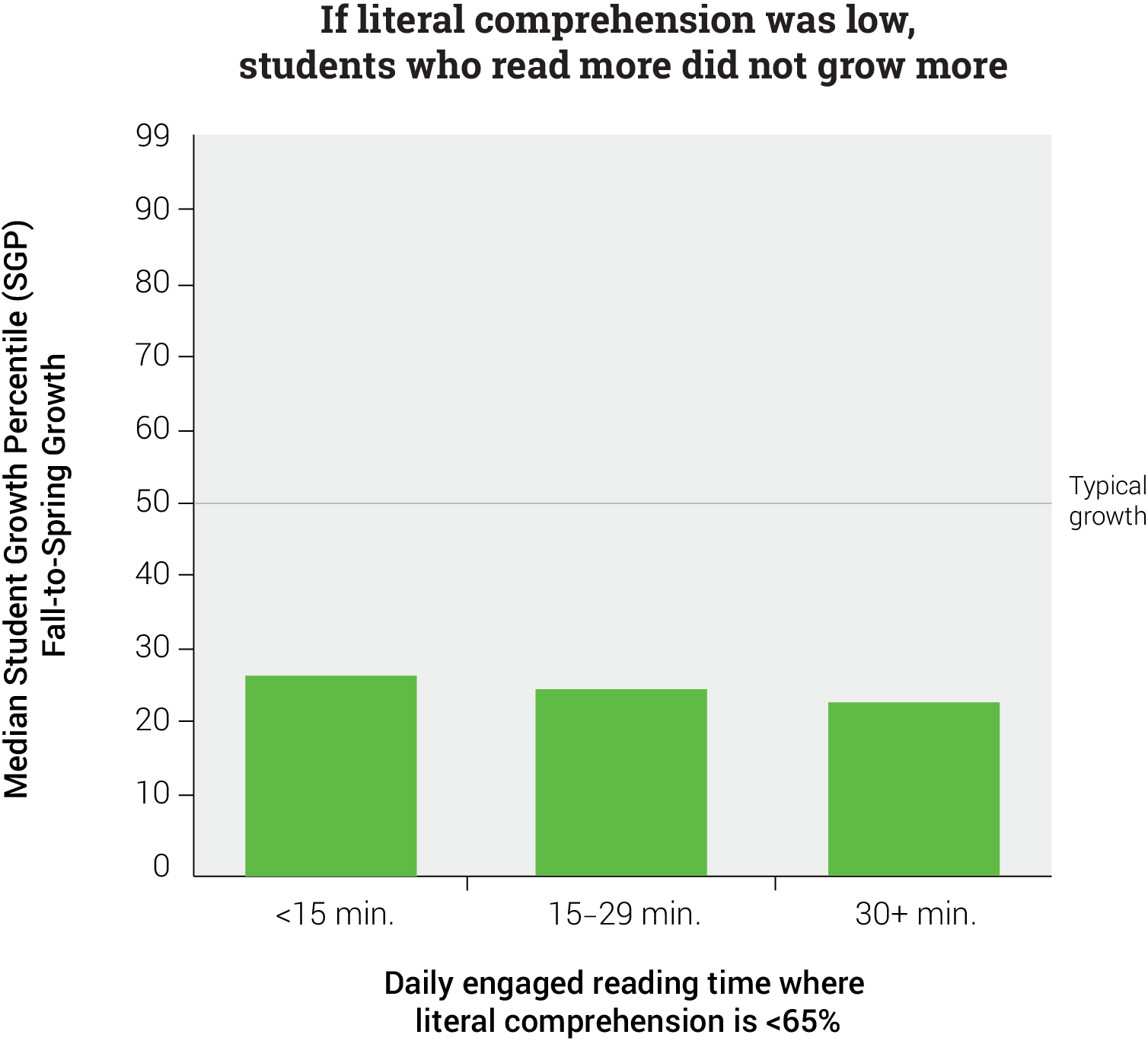

First, when literal comprehension was low, it didn’t matter how much time a child spent reading—growth stayed low. Increasing engaged reading time from less than 15 minutes to more than 30 minutes had almost no impact on Student Growth Percentile (SGP) gains if literal comprehension remained low. In other words, if students aren’t able to understand what they are reading, spending more time reading won’t significantly boost growth. In all three scenarios, growth remained well below average.

It should be noted that if a student scores below 60% on an individual book quiz, time spent reading that book is not considered “engaged reading time” as the student was not able to meaningfully engage with the book. A student who spends hours and hours reading but consistently scores below 60% on quizzes will have zero minutes of engaged reading time. This student would be included in the < 15 min group in the graph above. If anything, the graph understates how little impact additional reading has when literal comprehension is low.

Second, if literal comprehension was high, indicating high-quality reading practice, even a few minutes of reading were extremely valuable. Even students who read less than 15 minutes with high literal comprehension saw greater than typical growth, and growth increased the longer students spent reading. Students who had 30+ minutes of high-quality reading practice per day saw the greatest growth out of all groups analyzed with a median SGP of 83—far above typical growth (SGP of 50).

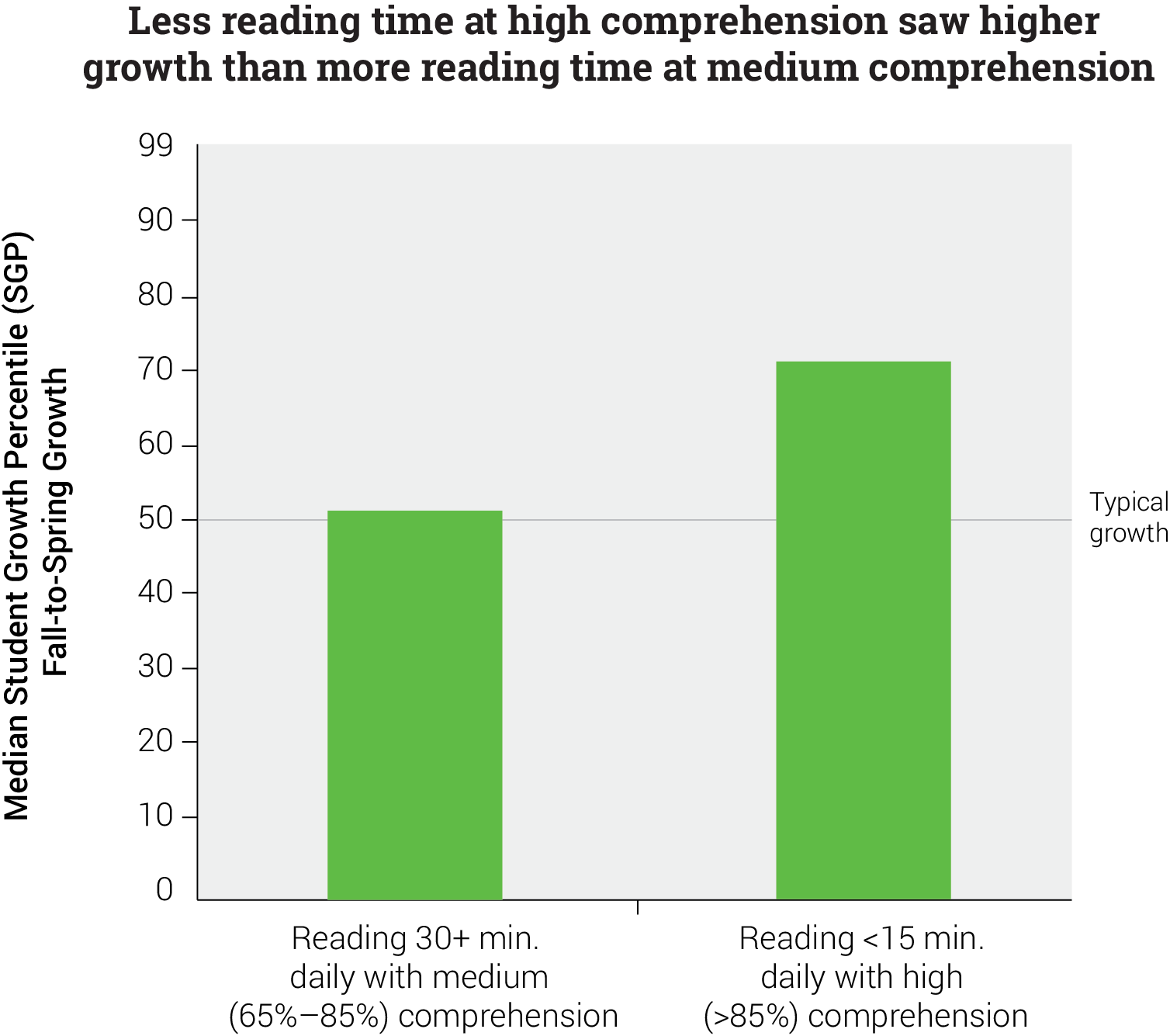

Furthermore, students who read for even a few minutes (less than 15) with high comprehension showed greater growth than those who read more than twice as long (30+ minutes) with medium comprehension. The high-comprehension, short-time group had a median SGP of 71, well above typical growth, while the medium-comprehension, long-time group had an SGP of 51—essentially typical growth (50). Based on this data, educators may want to put as much attention on comprehension as they do on reading time, if not more.

Third, high literal comprehension is most commonly associated with longer engaged reading times. When looking at only those students who averaged 85% or better on literal comprehension quizzes, we see most (72%) had at least 15 minutes of engaged reading time per day. The largest group (43%) had 30 or more minutes of engaged reading time per day.

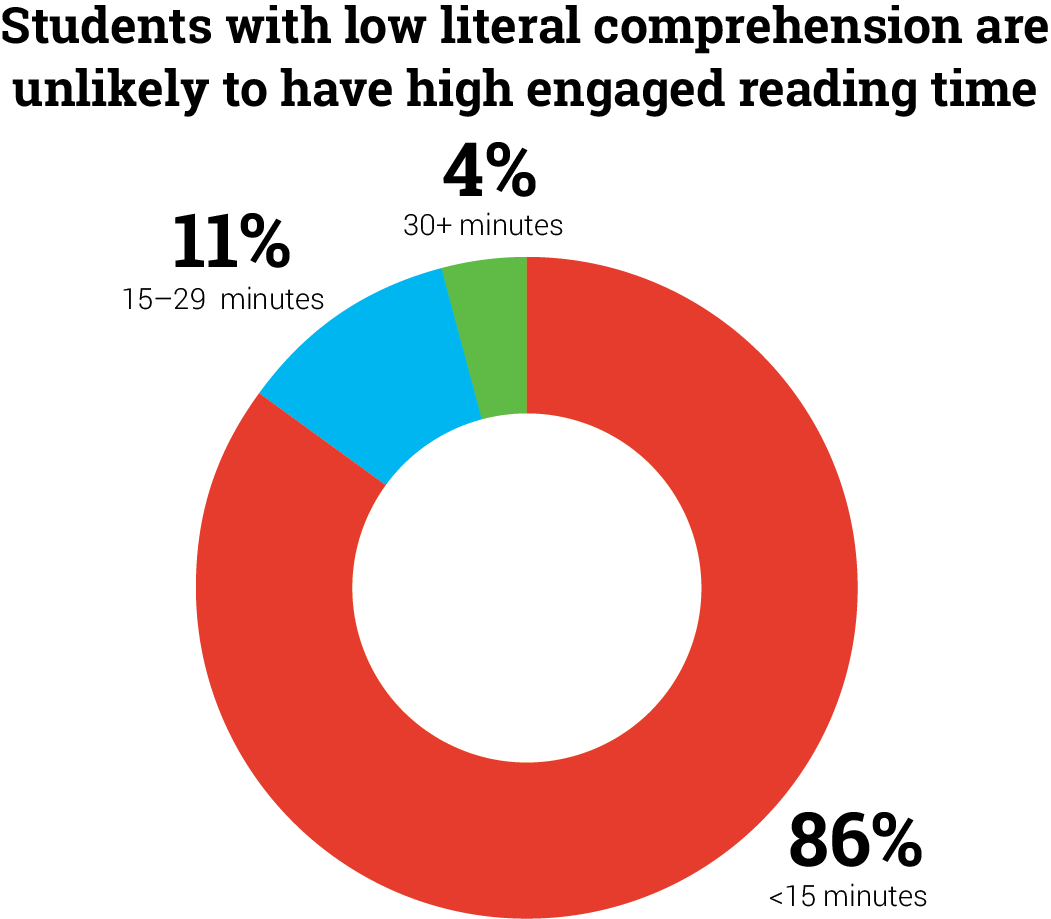

At the opposite end of the spectrum, when looking at only those students who averaged less than 65% on literal comprehension quizzes, we see the vast majority have less than 15 minutes of engaged reading time per day. As explained above, comprehension is used to calculate engaged reading time, so it’s not surprising this group had low engaged reading time.

However, it’s not impossible to have low average literal comprehension and high engaged reading time—15% of this group had 15 or more minutes of engaged reading time per day, including the 4% that even managed 30+ minutes—it’s just incredibly rare.

For students in this group, focusing on increasing comprehension would be a better option than simply reading for longer at the same low level of comprehension. The typical Student Growth Percentile (SGP) of students with low literal comprehension and less than 15 minutes of engaged reading time was 13; the SGP of students with low literal comprehension and 30+ minutes of reading time was 11. Even when reading stayed under 15 minutes per day, going from low literal comprehension (< 65%) to medium literal comprehension (65%–85%) increased SGP from 13 to 30; increasing literal comprehension further to high levels (> 85%) brought SGP up to 71.

That’s not to say reading time doesn’t matter. Reading time does matter quite a lot, as we saw in the second entry in this series, but it needs to go hand-in-hand with comprehension.

We would guess that the relationship between comprehension and reading is not a simple causal one, but more intertwined—improved comprehension skills may inspire a student to spend more time reading, while an increase in engaged reading time may help students hone and improve newly learned comprehension skills. We would recommend that educators spend time teaching reading comprehension strategies and also make sure that students have enough time to practice and master those strategies.

Reading practice and college and career readiness

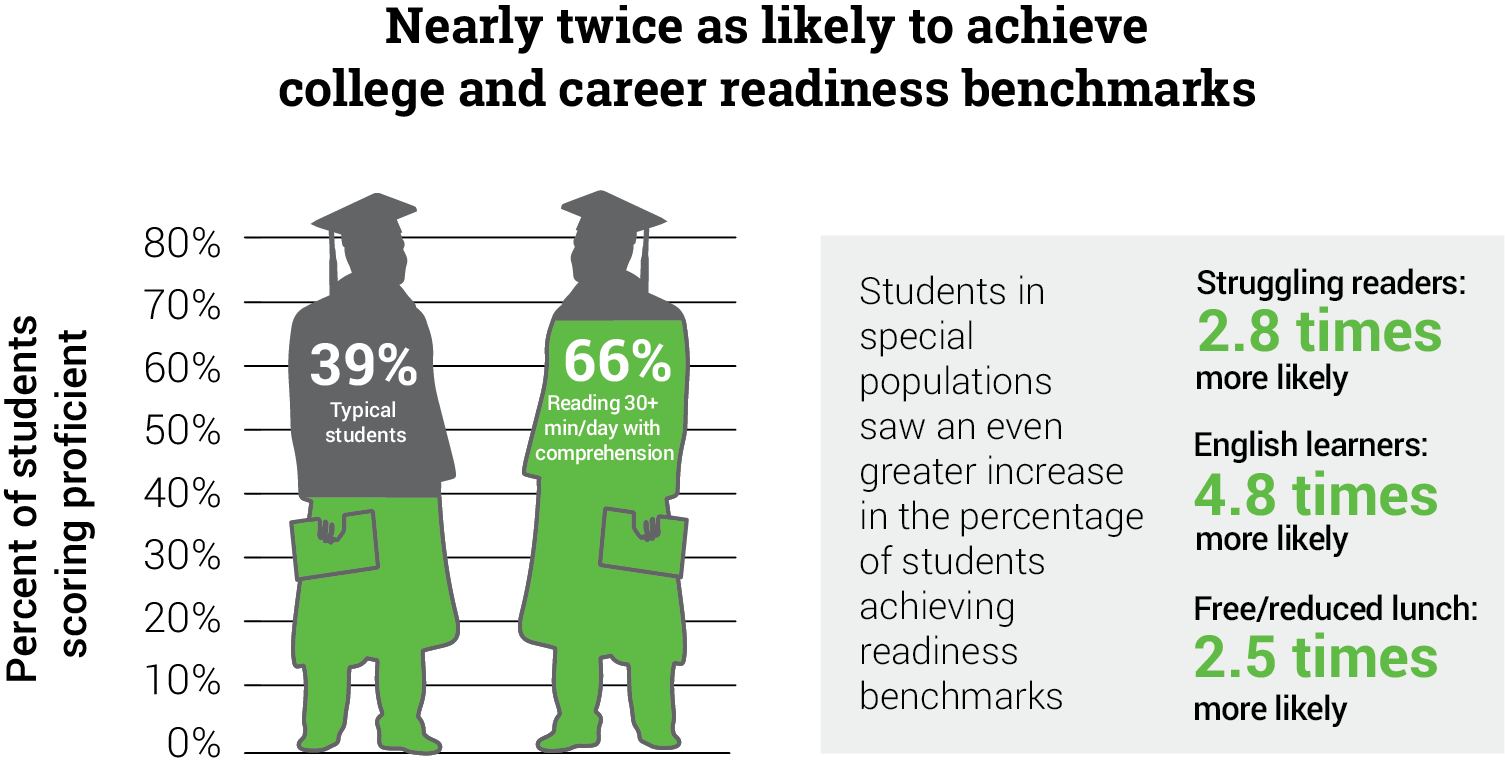

Students who spend lots of time reading and read with high comprehension are more likely to have higher levels of growth. They are also more likely to have higher levels of college and career readiness.

A study of 2.8 million students found that students who read 30+ minutes per day with high comprehension (85% or higher) were nearly twice as likely to achieve the college and career readiness benchmarks for their grade as typical students. The increase was even more dramatic among special populations, with students in free- and reduced-lunch programs seeing a 2.5 increase in college and career readiness, struggling readers seeing a 2.8 increase, and English Learners seeing a whopping 4.8 increase.2

What’s especially impressive is how easy this approach is, requiring only simple literal comprehension quizzes that students can complete in minutes after reading a text, without teachers needing to go through the time-consuming process of scheduling or administering a formal screener or assessment on a weekly or biweekly basis. However, teachers can’t be expected to read every book their students read and write corresponding quizzes, so a high-quality reading practice program that provides quizzes for lots of different texts, automatic scoring, and easy reporting is absolutely essential for this growth-accelerating approach.

A quick note about those literal comprehension quizzes. While it may be tempting to use these quizzes to both monitor ongoing growth and provide students with letter grades, educators should be very cautious about the latter.

Consider a student who chooses to read a book about airplanes that’s above her ZPD because she wants to better understand her father’s favorite hobby. She might struggle comprehending the whole text, faltering on words like aerodynamics and fuselage and not fully understanding the concept of wingtip vortices. However, at the end of the book she’s proud and excited about what she has learned—and can’t wait to surprise her dad with her new knowledge—despite scoring 65% on a literal comprehension quiz.

Her teacher has two options. He can give the girl a D grade based on her literal comprehension score, which may discourage her from reading further about STEM topics or risking any books above her ZPD for fear of lowering her grades. Or he can view the low comprehension score as a learning opportunity and guide her to a kid-friendly resource—like NASA’s student site—to help her learn the vocabulary and concepts. This can also help instill the idea that failure isn’t the end of learning, but sometimes just step upon the path to mastery, and build up the student’s resiliency and growth mindset.

In theory, the teacher could do both, but research shows that when students get both grades and feedback, they focus only on the grades and the feedback doesn’t really register.3, 4

A better option might be grading students based on progress toward a set of personalized goals.

However, we recognize that grades may be needed in many situations. For these, a better option might be grading students based on progress toward a set of personalized goals. For example, if a teacher sets a goal of 7.5 hours of reading per month (about 15 minutes per day) and a child reads 6.0 hours, he might receive a grade of 80%. Teachers could also set goals for maintaining a certain level of average literal comprehension across multiple texts, keeping reading logs, or reading a certain number or percentage of texts within or above a student’s ZPD. All of these options would allow our airplane-loving student to try harder texts on occasion, while encouraging her to keep the majority of her reading within her ZPD, and to always try her best to comprehend what she reads.

This prompts our next big question: How can educators set appropriate reading goals and keep students motivated to read? In the next blog post, we take a look at the surprising relationship between motivation and achievement, the role of personalized goals, and the many dimensions of motivation.

References

1 Renaissance Learning. (2015). The research foundation for Accelerated Reader 360. Wisconsin Rapids, WI: Author.

2 Renaissance Learning. (2017). Trends in student outcome measures: The role of individualized reading practice. Wisconsin Rapids, WI: Author.

3 William, D. (2011). Embedded formative assessment. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.

4 Brookhart, S. M. (2008). How to give effective feedback to your students. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.