June 10, 2022

At Renaissance, we’re committed to providing students with access to engaging content that is inclusive and representative of the students and diverse communities we serve. Our content developers aim to provide students with both a “mirror,” so they may see themselves uplifted in the material, and a “window,” so they may learn about others’ cultures, customs, and perspectives.

For our ELA and math practice products, such as Freckle and Lalilo, working toward this goal of inclusion has been relatively straightforward. We seek to increase the representation of different groups of people, including significant cultural artifacts, customs, and traditions. Diversifying cultural representation can be a bit more challenging for our assessment products, however. How so? Because there is potential to introduce irrelevant content into the question that may distract, advantage, or disadvantage certain test-takers. In this blog, we’ll explore this point in detail and describe the important work the Star Assessments content team has done as they work to create unbiased and culturally representative assessments.

Understanding bias in assessment design

A high-quality assessment is one that is fair or, in other words, free from bias. Fairness in assessments suggests that the individual questions—known as items—are equally challenging to all students, regardless of their racial, social, or geographic background. Attempts to make assessments fair typically mean avoiding items that benefit some students not because of their knowledge of the construct being assessed, but because of extraneous factors, such as their socioeconomic status. Consider this hypothetical assessment item:

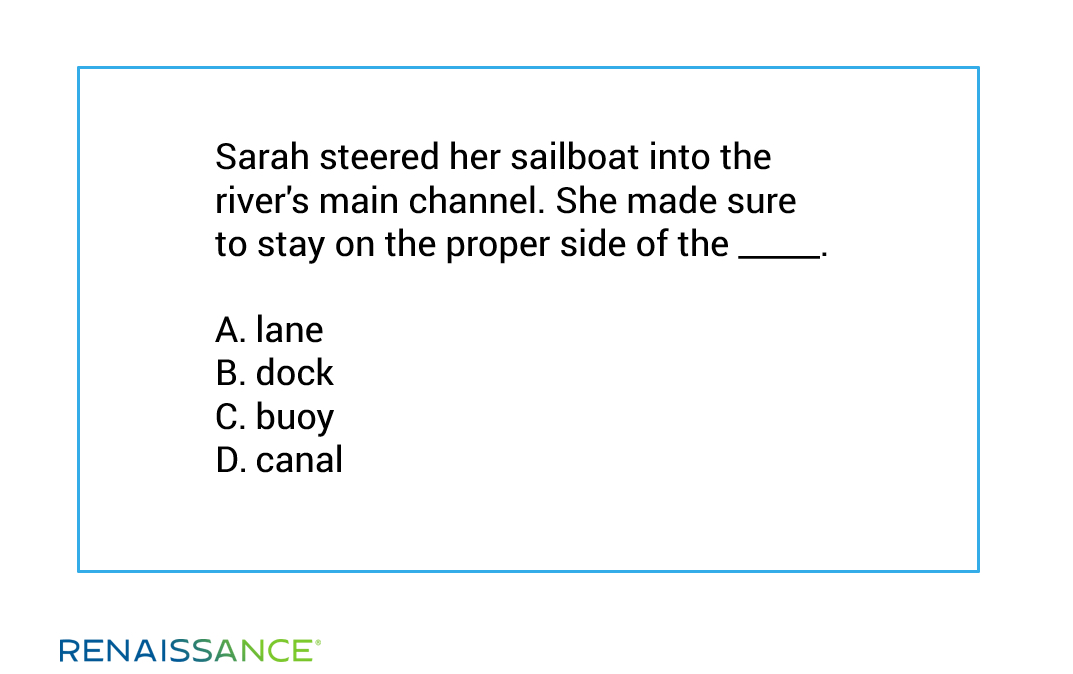

This item is intended to assess a student’s understanding of vocabulary in context, a core ELA learning standard in grade 3. The relative difficulty of the target word (“buoy”) is crucial to the standard being assessed, because it differentiates levels of vocabulary knowledge among test-takers. However, the item has some clear issues of potential cultural and socioeconomic bias. Sailing—and an understanding of concepts and terms related to boats, sailing, and navigation—is potentially more familiar to students who have economic advantage or who have cultural or regional familiarity with the subject. As a result, the item may unintentionally assess students’ knowledge of sailing, and a correct response may be due to reasons other than their understanding of vocabulary in context.

To reduce bias in contextual items like the one above, assessment developers have traditionally attempted to eliminate cultural references, as well as items biased in favor of people from certain socioeconomic groups or geographic regions. In these instances, contextual items would only cover general knowledge to ensure items assess the intended construct and not the students’ knowledge of information irrelevant to the construct (in this case, a knowledge of sailing).

The inherent problem with this practice is that “general knowledge,” by definition, excludes marginalized experiences and centers the largest or dominant social group. This unintentional yet non-inclusive practice can actually hinder other students’ performance and create a false achievement gap (Singer-Freeman, Hobbs, & Robinson 2019). Such is the dilemma of building culturally responsive, non-biased assessments: including cultural context has been said to disadvantage students from other cultures, yet research suggests that students perform best when material is made culturally relevant (Ladson-Billings, 2014). So, how do we create assessments that offer students windows and mirrors without introducing construct-irrelevant content that may distract students or offer an advantage to some students and not others? Our process involves three key principles.

Principle 1: Recognize the role of culture in assessment

We start by accepting that there is no such thing as a culture-free assessment. It can be argued that everything around us is an artifact of culture. Culture extends beyond language, food, and customs. The utensils we use or don’t use while eating, the interactions we have with elders, and even our preferences for solo or group leisure activities are all influenced by culture. Researchers have found that this can be extended to education as well (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018). Our preference for how we learn concepts and demonstrate mastery is influenced by our cultures, as are the methods we use to teach concepts and assess students’ understanding. Consider this hypothetical item, which may seem to be culture-free at first glance:

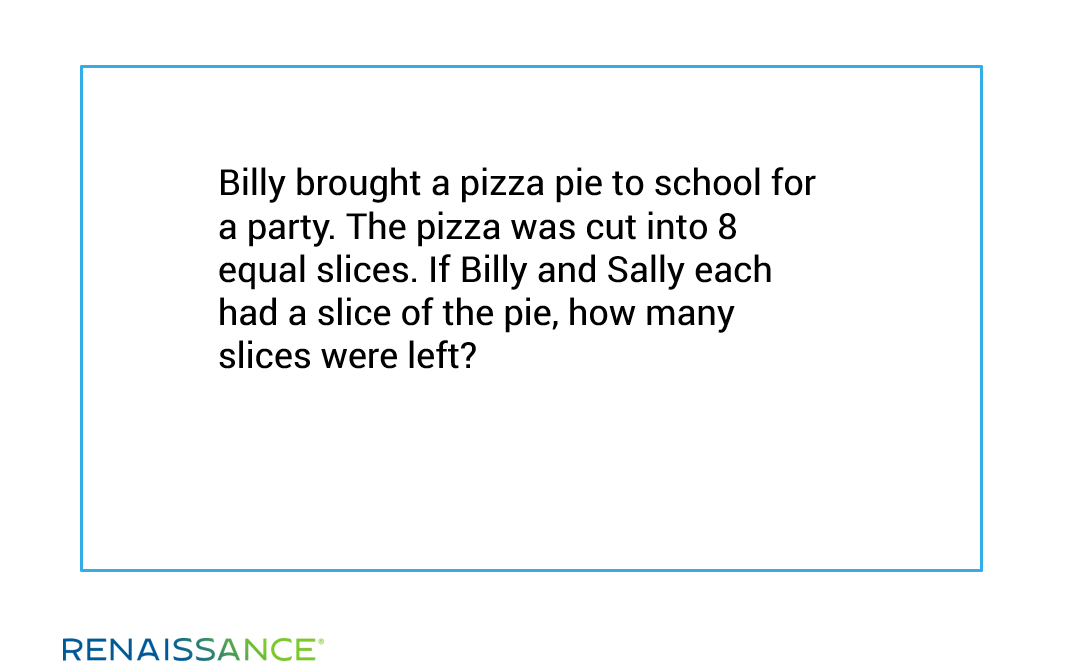

For students in the United States, what could be more familiar than pizza? That’s a more complicated question than it might seem. The intent of such an item is to make a math question more engaging by providing relevant contextual information. But while it’s easy to assume that all students are familiar with pizza—and know that it’s sometimes called “pizza pie”—this generalization obscures potential regional, ethnic, and socioeconomic biases. At Renaissance, we’re aware that students accessing our products come from diverse cultural backgrounds and that some students, such as those who recently migrated to the United States, may not consider pizza to be a typical dish (or a type of pie).

To be clear, this item is appropriate and does not provide an advantage to students familiar with pizza pies. But when developing culturally inclusive assessment items, we try to avoid limiting contextual content to only that with which most students are familiar. Such a practice may unintentionally perpetuate the marginalization of minority students, as this example shows.

Does this mean that we avoid writing about pizza, or about culturally specific material altogether? No. Rather than attempting to remove cultural context from items, we seize the opportunity to develop culturally competent students. To reiterate a key point from an earlier blog, cultural competence refers to helping students appreciate and celebrate their cultures while learning about at least one other culture. This has required a shift in our approach to content development to ensure we provide room for all cultures and do not center the “mainstream” or majority culture.

As the education community comes to accept that there is no such thing as culture-neutral, culture-blind, or culture-free assessments, student assessments should shift from focusing solely on removing culture-specific content to intentionally including culture-rich content that allows more students to see themselves uplifted. So, how do we create culturally relevant assessments for a diverse audience?

Principle 2: Ensure assessment items are bias-free

We ensure our contextual items that introduce students to various cultures do not require knowledge of those cultures to respond correctly. Our process begins with actively including a wide and diverse array of cultures and groups of people involved in a variety of cultural practices (some that stand out as distinct from “mainstream” cultural practices and some that do not, such as American football). Diversity across our Star Assessments item banks is carefully tracked and adjusted through new item development, and the editorial process includes multiple reviews to ensure that items are bias-free and fair measures of the construct being assessed.

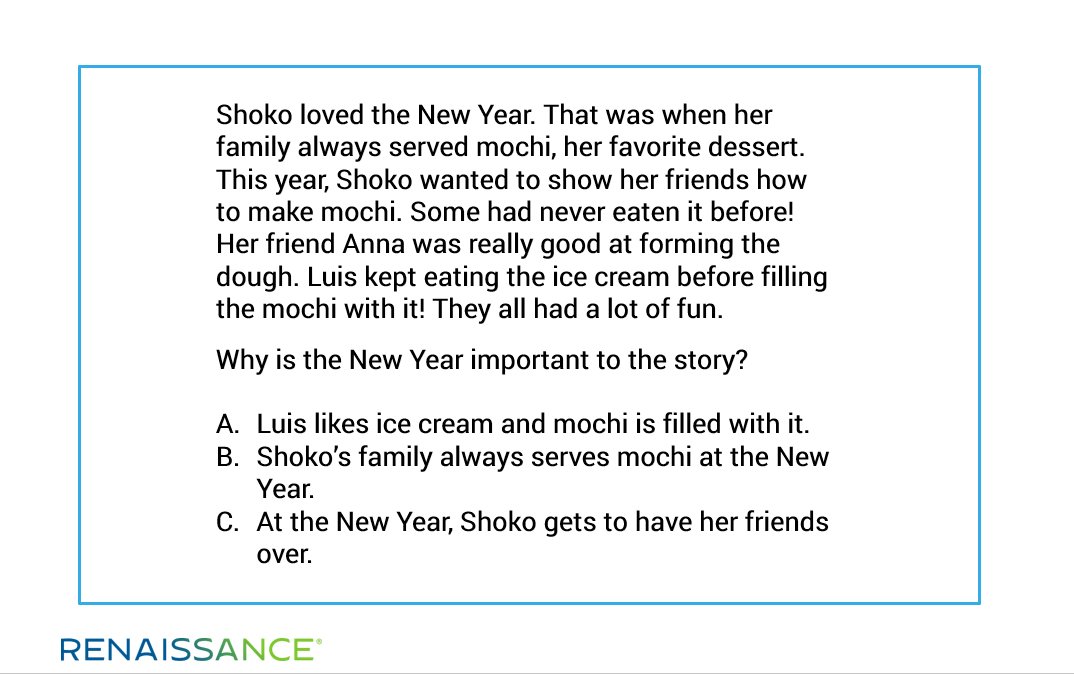

Prior to new items being accepted into our item banks, they are statistically analyzed for indications of biases and any flagged items are rejected. The following is an example of an item recently developed to support our goals around culturally responsive assessment.

This item, like the previous pizza-party item, provides an example of how an assessment question can provide both a window to other cultures and a mirror for those belonging to that culture. It is important to note that the cultural content serves to provide additional context to the question, but knowledge of the culture is not required to respond correctly. This is the defining characteristic of a culturally relevant, bias-free item.

Principle 3: Strive for accuracy and respect

When we do feature different groups, we ensure our portrayals are respectful and accurate. As we develop culture-rich assessment items, we make intentional efforts to portray all groups in a positive and accurate light. Our content teams research and engage in conversations with people from varying ethnic and cultural groups to build an understanding of significant cultural artifacts (e.g., foods, holidays). Our content development guidelines are regularly updated to include our learnings and offer appropriate ways to address different groups and topics. We fact-check our sources and, when possible, share potential items with members of those communities to gauge appropriateness.

Valuing culturally relevant assessment

At Renaissance, we understand that students perform best when they can learn and demonstrate learning in a manner that is relevant to them. We have begun exploring how culturally responsive practices may look in assessments, starting with creating culture-rich assessment items that are still bias-free. This continues to be a work-in-progress, and we’re excited to track and share our learnings with the broader education community as we continue this important journey.

References

Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: a.k.a. the remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84, 74–84.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2018). How people learn II: Learners, contexts, and cultures. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/24783

Singer-Freeman, K. E., Hobbs, H., & Robinson, C. (2019). Theoretical matrix of culturally relevant assessment. Assessment Update, 31(4), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.1002/au.30176

Learn more

Are you up-to-speed on everything that Star Assessments have to offer? Learn more about Star curriculum-based measures in English and Spanish, the new Star Phonics, and much more.