January 16, 2018

This post is the first entry in the Education Leader’s Guide to Reading Growth, a 7-part series about how education leaders can use research-driven strategies to support reading growth and achievement—and improve student outcomes.

What are the differences between a student who starts and ends the school year as a struggling reader, and a student who starts out struggling but ends the year succeeding?

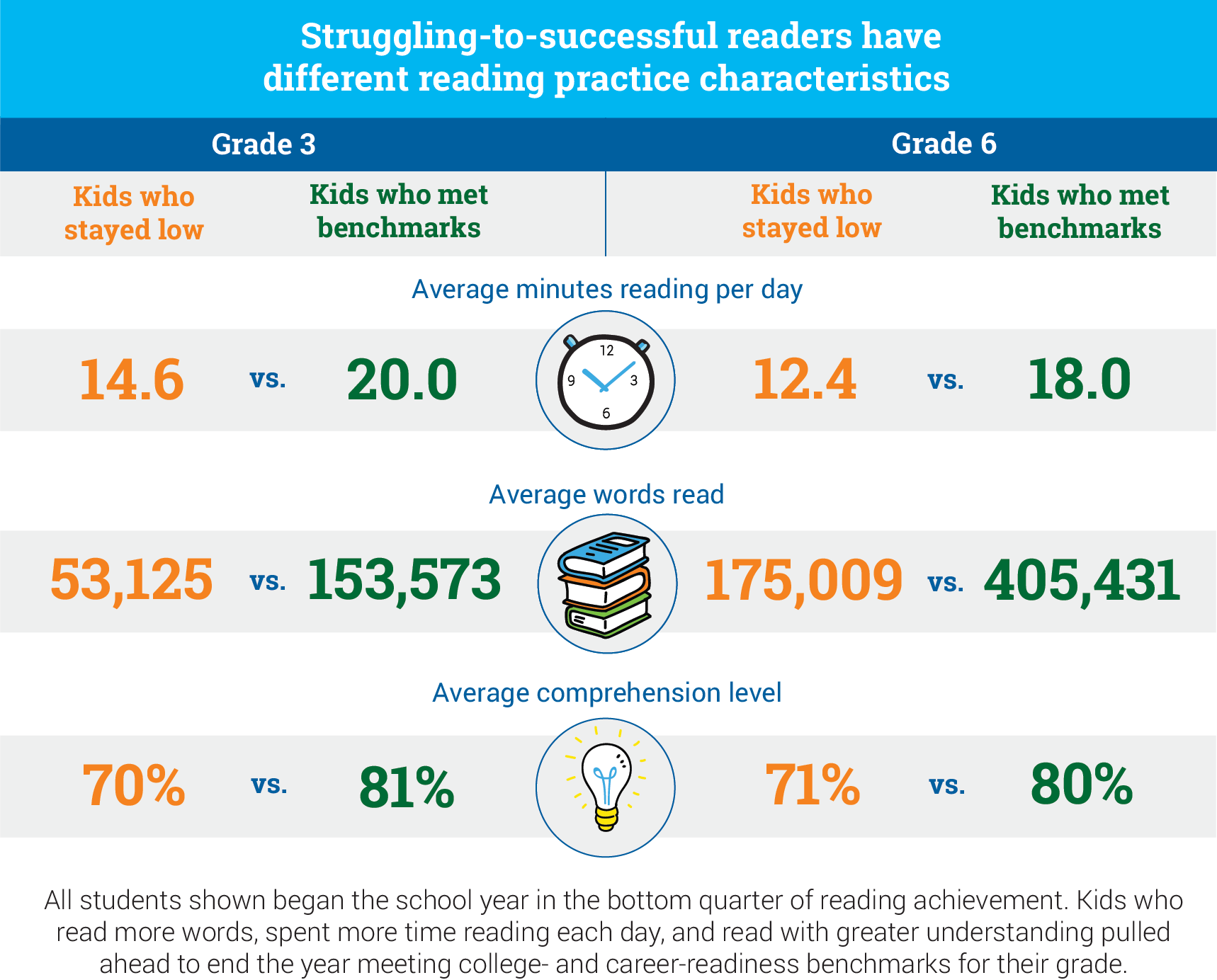

A recent study comparing the two groups noted several differences in their reading practice characteristics, and one of them was the time spent reading per day. Students in the latter group—the “successful” readers—read approximately six minutes more per day on average.

In the world’s largest study of the reading habits of K–12 students—encompassing nearly 9.9 million students in more than 30,000 schools across the United States over the 2015–2016 school year—the authors also found differences in average words read (successful readers read more words) and quality of the reading practice as measured by the average comprehension level (successful readers had higher comprehension).1

The study first looked at third-grade students who began the school year in the bottom quarter of reading achievement—struggling readers who would typically be identified as needing “intervention” or even “urgent intervention.”

On average, the third graders who failed to meet grade-level benchmarks by the end of the year had 14.6 minutes of engaged reading time per day. In comparison, the third graders who met the college- and career-readiness benchmarks for their grade read for 20.0 minutes—a difference of less than 6 minutes of daily reading time. On average, these students also read 100,448 more words and had 11% higher comprehension than their peers who did not meet benchmarks.

The study next looked at sixth-grade students. Sixth graders who started the year in the bottom quarter and ended the year below benchmark read an average of 12.4 minutes per day. Sixth graders who started in the same place but achieved college- and career-readiness benchmarks averaged 18.0 minutes of engaged reading time per day. Once again, the difference in daily reading time was less than 6 minutes. These students also read more words on average (230,422 more) and had higher average comprehension (9% higher).

It’s important to recognize that engaged reading time is not the same as time spent looking at a page. It’s calculated based on the text’s total word count and difficulty/complexity level as well as the child’s individual reading level and overall comprehension of the text. For example, reading the same page for an hour without understanding its meaning counts as zero minutes of engaged reading time. (More information about how engaged reading time is calculated can be found here.)

While the study did not examine other variables that can affect achievement—such as quality of instruction or socioeconomic status2—the data show that students who struggle initially but then begin to dedicate significant time to reading with high understanding can experience accelerated growth during the school year. This implies that, in addition to the high-quality instruction and intensive support that we know are essential for struggling readers to learn reading skills,3 time to practice applying those skills is also important.

It also indicates that reading practice isn’t simply an effect of a student’s reading skills. While it’s true that students who read well tend to read more, the fact that students who started at the same skill level but ended the school year with very different outcomes after engaging in different amounts of reading practice suggests that high-quality reading practice could help make significant contributions to growth. In other words, reading practice can be a sign of stronger reading skills, but it can also help build stronger reading skills.

What makes this particular revelation—that a small increase in daily reading time may play a role in turning a struggling reader into a successful one—even more eye-opening is the long-term impact reading skills (or a lack of reading skills) can have in a student’s academic career.

Struggling readers in third grade

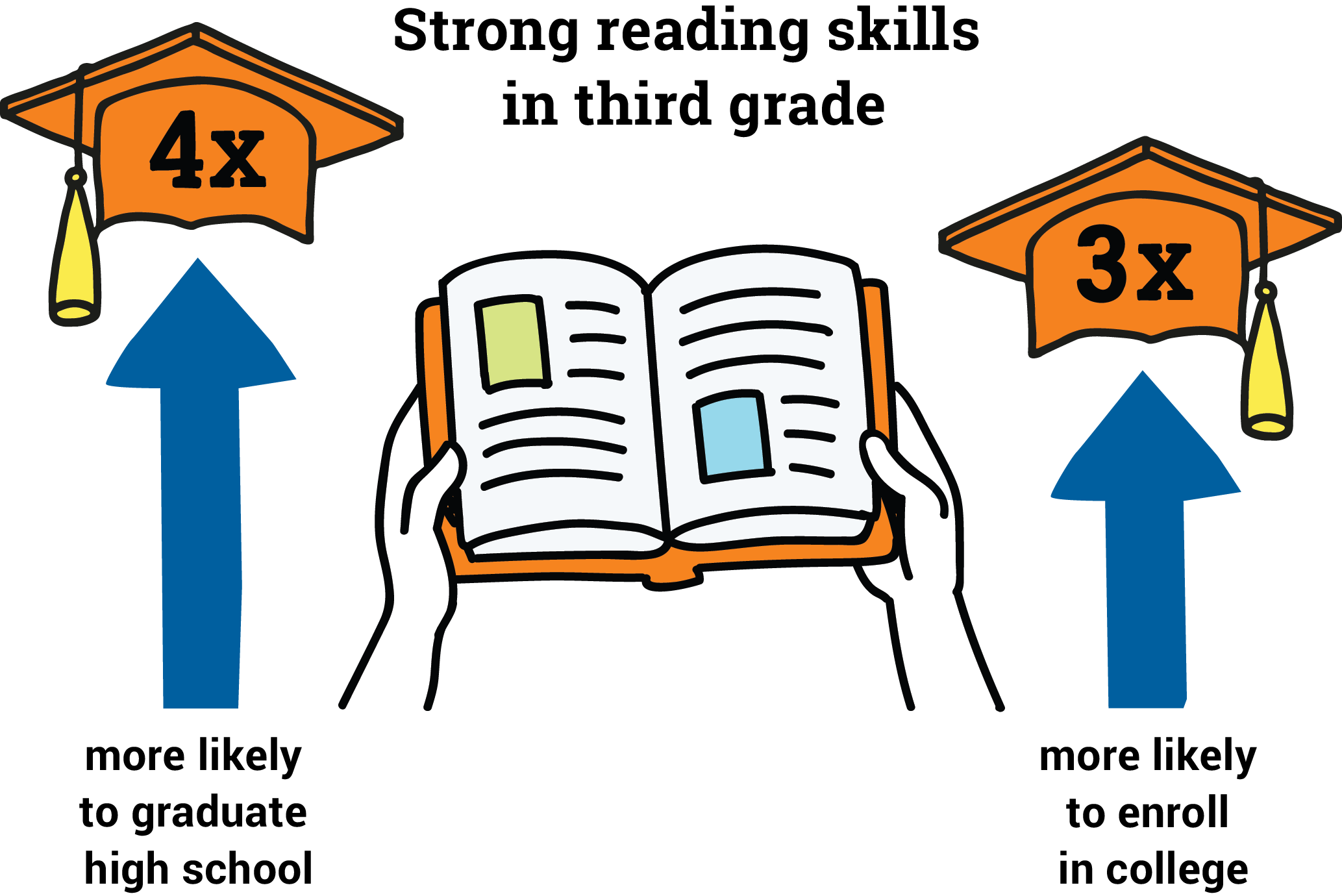

A longitudinal study of nearly 4,000 students found that children who read proficiently in third grade were four times more likely to graduate on time than peers who were not proficient in reading in third grade. In fact, nearly one in six students who did not read proficiently in third grade did not graduate high school by age 19.4

When looking at only those students who were far below proficient—students categorized as having “below basic” reading skills—the rate dropped even further, with almost one in four students failing to graduate on time. Among students who did read proficiently in third grade, only one in twenty-five had not graduated high school by age 19.

Another longitudinal study, this time of 26,000 students, found that less than 20% of students who were in the bottom quarter of reading achievement (0–24th national percentile) in third grade went on to attend college. At the other end of the scale, nearly 60% of the students who were in the top quarter of reading achievement (75th–100th national percentile) enrolled in college.5

In other words, the strongest readers—students who were in the top quarter of reading achievement in third grade—were nearly three times more likely to enroll in college than peers who struggled with reading and were in the bottom quarter of reading achievement.

Considering the numbers, the question must then be asked: Could a few additional minutes of engaged reading practice each day, combined with high-quality instruction and other supports, help a struggling third-grade student get on a trajectory toward high school graduation and college enrollment?

Struggling readers in sixth grade

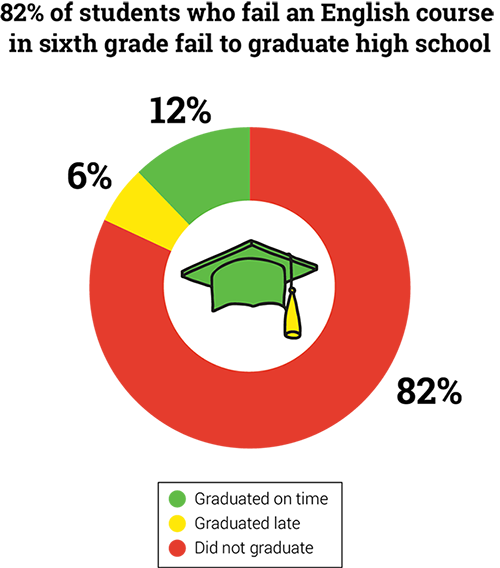

If elementary reading performance has a role in high school graduation rates, then middle-school reading performance is even more critical. A longitudinal study of almost 13,000 students found that only 12% of students who failed an English course in sixth grade graduated high school on time. Another 6% graduated late. The remaining 82% did not graduate by the time the study had ended.6

It should be noted that sixth grade is part of a period during which reading gains experience the biggest decline. Over the course of a student’s education, yearly reading gains typically decrease as they move through the grades—which is the normal pattern for cognitive development and not a cause for concern. Students often see very large reading gains in early years; the difference between a student’s reading skills in second grade and third grade is much greater than the difference between skills in tenth and eleventh grades. However, the rate at which reading gains slow is not steady across all years—and sixth grade is part of a period during which that rate is lowest.

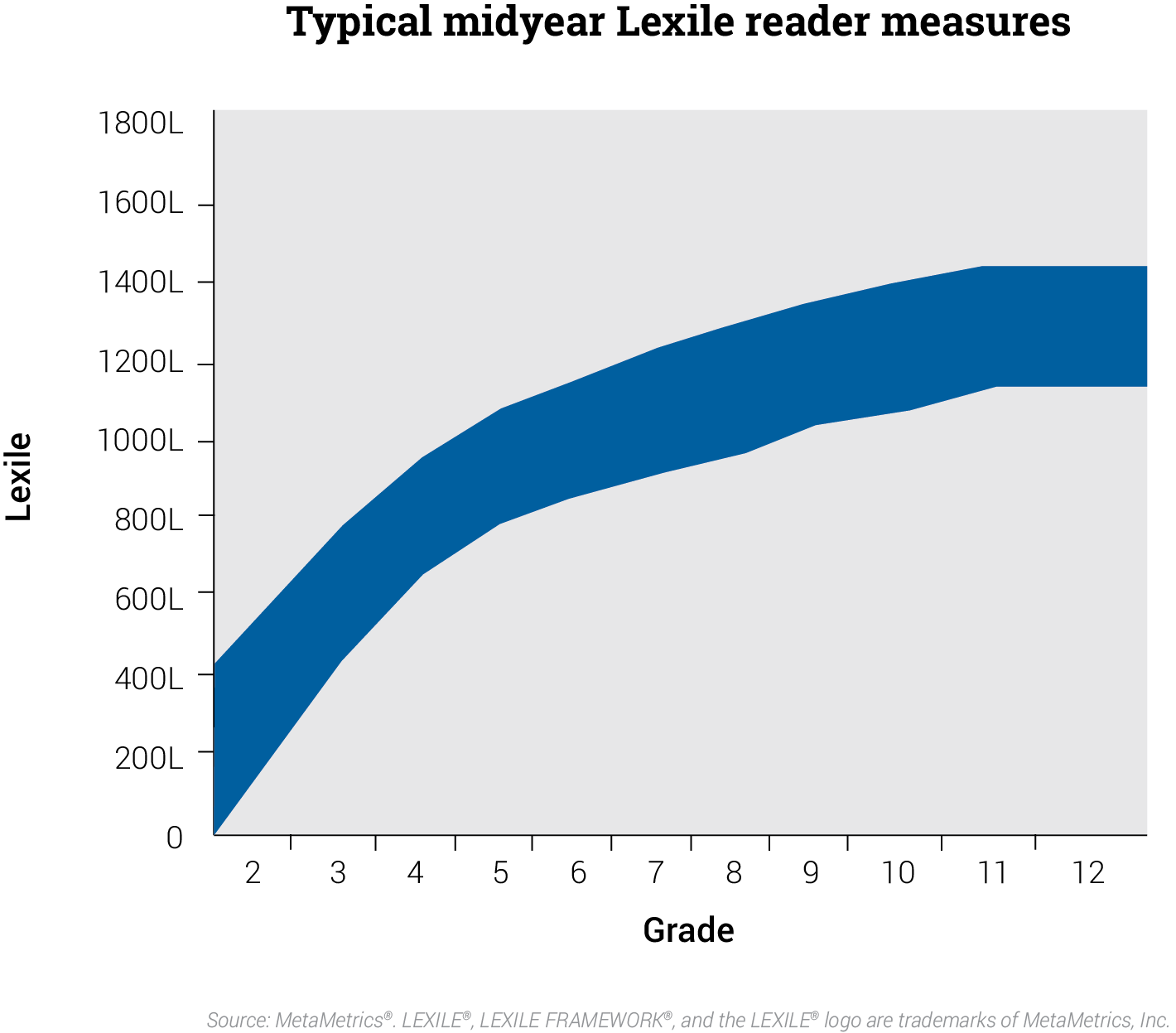

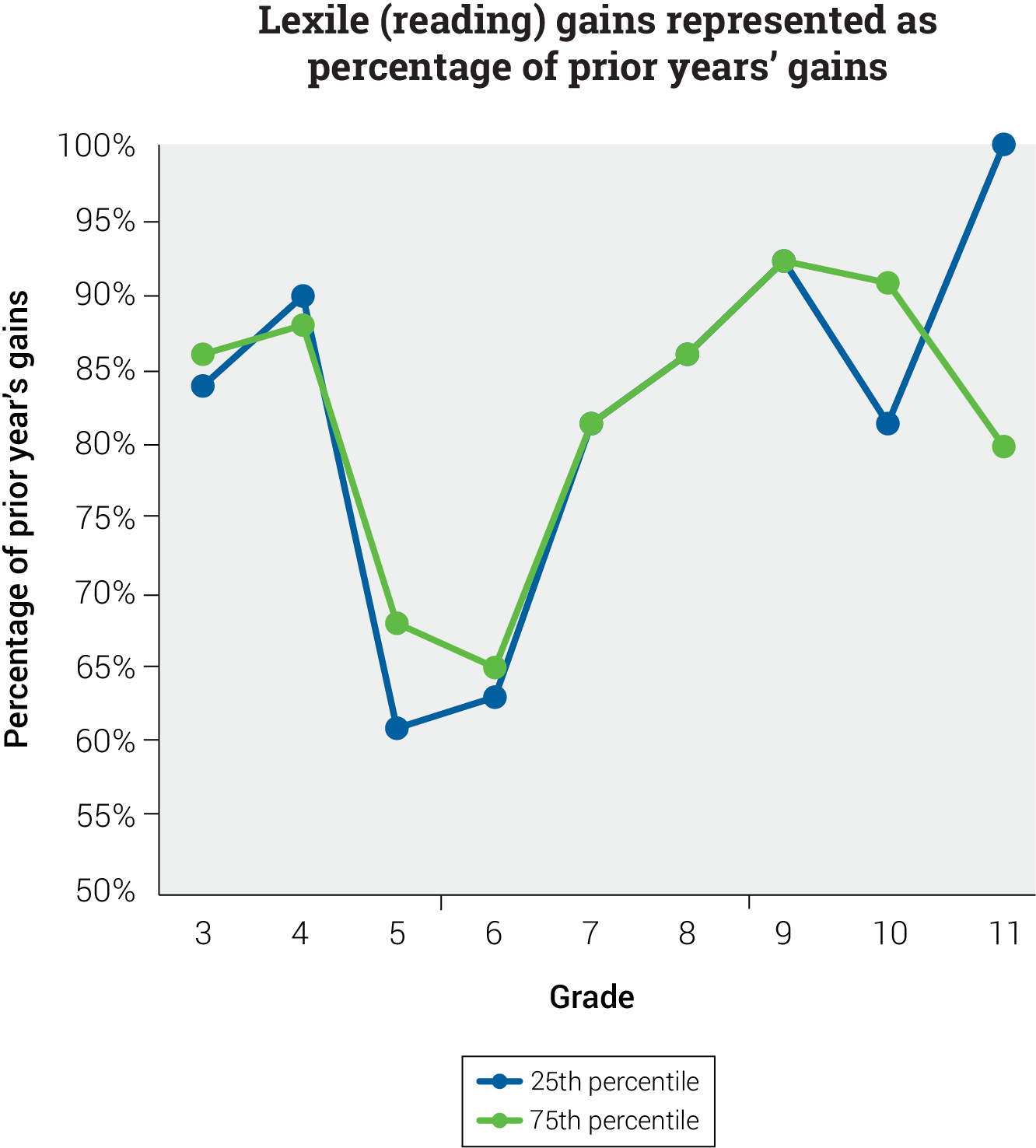

If you chart typical midyear Lexile® reader measure ranges (25th percentile to 75th percentile) across multiple grades, you’ll end up with a curve that starts fairly steep and softens as the years go by.7 Viewing the data this way, it’s easy to see that there is room for improvement, but it’s hard to see why we would look more closely at any grade range in particular.

However, if you look at only the changes in typical Lexile reader measure ranges across the years, a different pattern emerges. Here we do not see a steady decline across the years, but instead a steep drop at the fifth and sixth grades.

For most grades, the increase in both the upper and lower boundaries is 80% to 100% of the prior year’s increase. From tenth to eleventh grade, the upper boundary increases by 40L, which is 80% of the increase between ninth and tenth grade (50L), which is turn is 91% of the increase between eighth and ninth grade (55L)—and that is 92% of the increase between seventh and eighth grade (60L). However, between fourth and fifth grade the increase drops to 61% for the lower boundary and 68% for the upper boundary, and between fifth and sixth grade the increase drops to 63% for the lower boundary and 65% for the upper boundary.

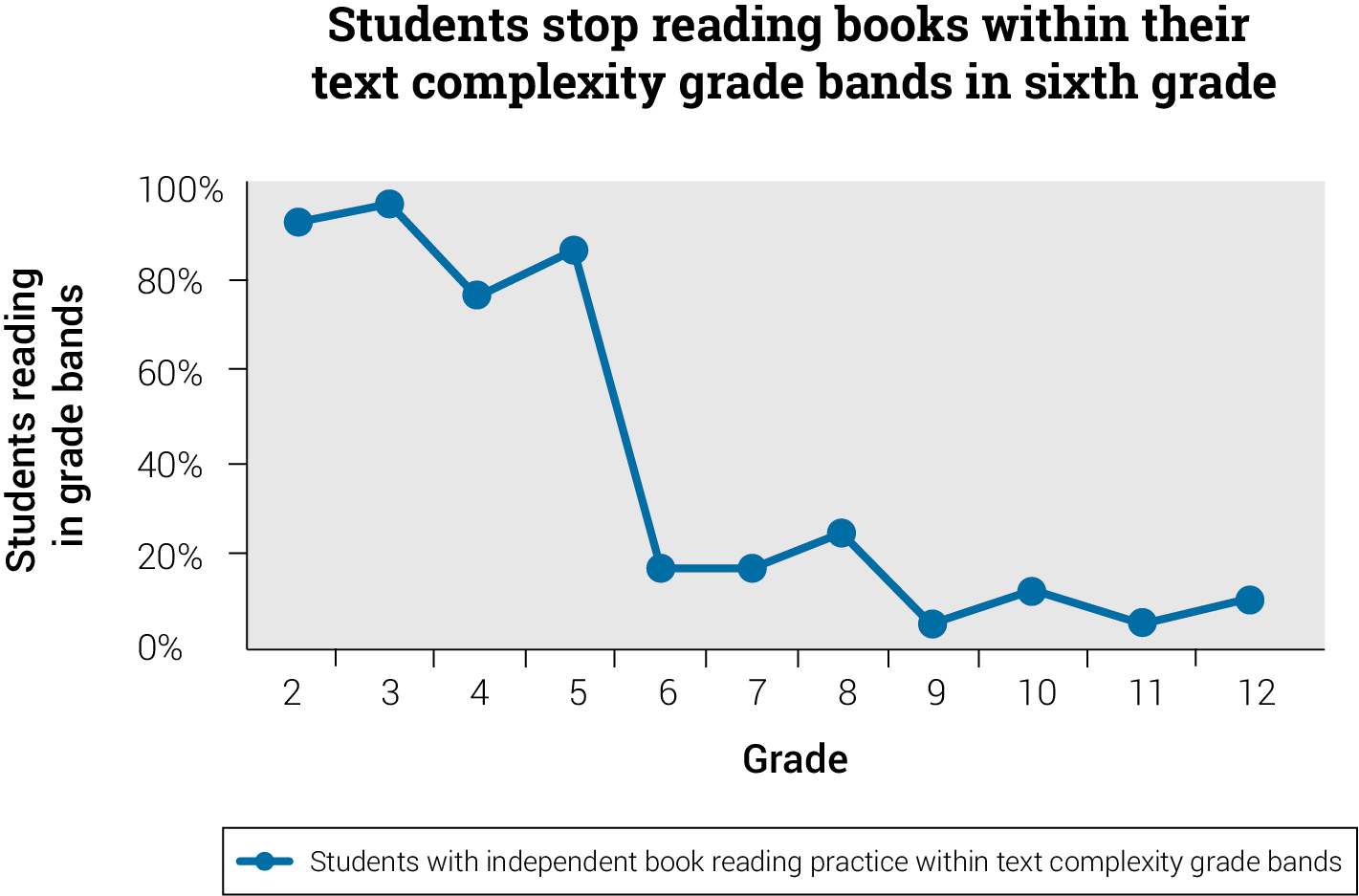

It is at sixth grade that students stop independently reading books within the text complexity bands for their grade. Between second and fifth grades, the vast majority of students read at least one book in their target grade band. In sixth grade, that number plummets below 20% and never really recovers. From sixth grade through high school, less than 15% of students, on average, read one or more books in their target range.8

It is tempting to imagine what might happen if we were able to reverse these trends. If a few additional minutes of daily reading practice may help struggling readers transform into successful readers, could this also help change these students’ entire academic trajectories? What if adding a few minutes of high-quality reading activities in our elementary classrooms reduced the total number of struggling readers in middle school? Could those minutes keep them reading within their text complexity grade bands, not just in sixth grade but in future grades?

What if we made a few additional minutes of daily reading practice a reality for all struggling readers, in all grades?

Let us be clear: We are not saying that six minutes of reading time is all you need to turn struggling readers into successful readers. We are saying that, if you have struggling readers in your schools, or if you have ever been concerned about your students’ reading achievement levels or graduation rates, reading practice must be one of your top priorities.

However, it’s not just struggling readers who aren’t getting enough reading practice. In the next entry, we examine the relationship between reading practice and growth and show why increasing reading practice for all students needs to be a system-wide priority.

References

1 Renaissance Learning. (2016). What kids are reading: And how they grow. Wisconsin Rapids, WI: Author.

2 Baker, B. D., Farrie, D., & Sciarra, D. G. (2016). Mind the gap: 20 years of progress and retrenchment in school funding and achievement gaps (Research Report No. RR-16-15). Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

3 Gersten, R., Compton, D., Connor, C.M., Dimino, J., Santoro, L., Linan-Thompson, S., and Tilly, W.D. (2008). Assisting students struggling with reading: Response to Intervention and multi-tier intervention for reading in the primary grades. A practice guide. (NCEE 2009-4045). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/PracticeGuides

4 Hernandez, D. J. (2012). Double jeopardy: How third-grade reading skills and poverty influence high school graduation. Baltimore, MD: The Annie E. Casey Foundation.

5 Lesnick, J., Goerge, R., Smithgall, C., & Gwynne, J. (2010). Reading on grade level in third grade: How is it related to high school performance and college enrollment? Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

6 Balfanz, R., Herzog, L., & Mac Iver, D. (2007). Preventing student disengagement and keeping students on the graduation path in urban middle-grades schools: Early identification and effective interventions. Educational Psychologist, 42(4), 223–235.

7 MetaMetrics. (n.d.). Matching Lexile measures to grade ranges. Retrieved from https://lexile.com/educators/measuring-growth-with-lexile/lexile-measures-grade-equivalents

LEXILE®, LEXILE FRAMEWORK®, and the LEXILE® logo are trademarks of MetaMetrics, Inc.

8 Renaissance Learning. (2015). What kids are reading: And the path to college and careers. Wisconsin Rapids, WI: Author.