June 26, 2020

Note: This is the final blog in our series on using your assessment data to address learning gaps during the 2020–2021 school year.

Most people are familiar with Nike’s long-running “Just do it” marketing campaign. Shortly before this wildly successful campaign launched, Nike ran a far less famous—and shorter-lived—one. That earlier campaign, however, provided a slogan that one of our colleagues has used for years when discussing education: “There is no finish line.”

In particular, he used this message with his teaching staff each March, after the state test had been administered. Relieved to have state testing behind them, a few teachers would say, “Now we can relax.” For this reason, he sent an email the day after testing, reminding teachers that “There is no finish line! Today is the first day of next year’s scores.” He even found an original Nike t-shirt with this slogan and would wear it on those days to reinforce this message.

Why change is the only constant

Over time, many of us have come to understand that “There is no finish line!” is an enduring truth about our profession. It is a mantle we take on when we become teachers. There will always be more that we could do, more that we could teach our students. Our finish lines are typically drawn by time rather than by having met every predetermined outcome. We teach right up to the last minute of the class, the last moment before the test, and the last lesson before graduation, trying to give our students every skill, every piece of knowledge, and every advantage possible.

There’s also a clear benefit of not having a finish line. It gives us the opportunity every school year to reinvent ourselves. Our summers have typically been a time of rejuvenation and reflection about how to improve student outcomes in the new year by refining our craft, our pedagogy, and our commitment. This year, that challenge is even more apparent—and even more necessary.

COVID-19 has brought unforeseen disruptions to education and a heightened concern about the 2020–2021 academic year. Fears abound that students will have fallen behind and that there will be wider performance gaps than we’ve seen before. But, as we explained at the outset of this blog series, no teacher has ever started the school year with every student performing just as expected. We know how to deal with this. And yes, there will likely be a lot of variance in student performance this fall, but no teacher has ever taught a class where every learner is at precisely the same level. We have ways to address this as well.

Having said that, the global pandemic and this spring’s school closures have precipitated some changes—and have raised some important questions that require our consideration.

Benchmarks in the COVID-19 era

First and foremost, educators are asking: Should we keep the same benchmarks we used last year? Or should we make adjustments, in order to account for COVID-related learning loss?

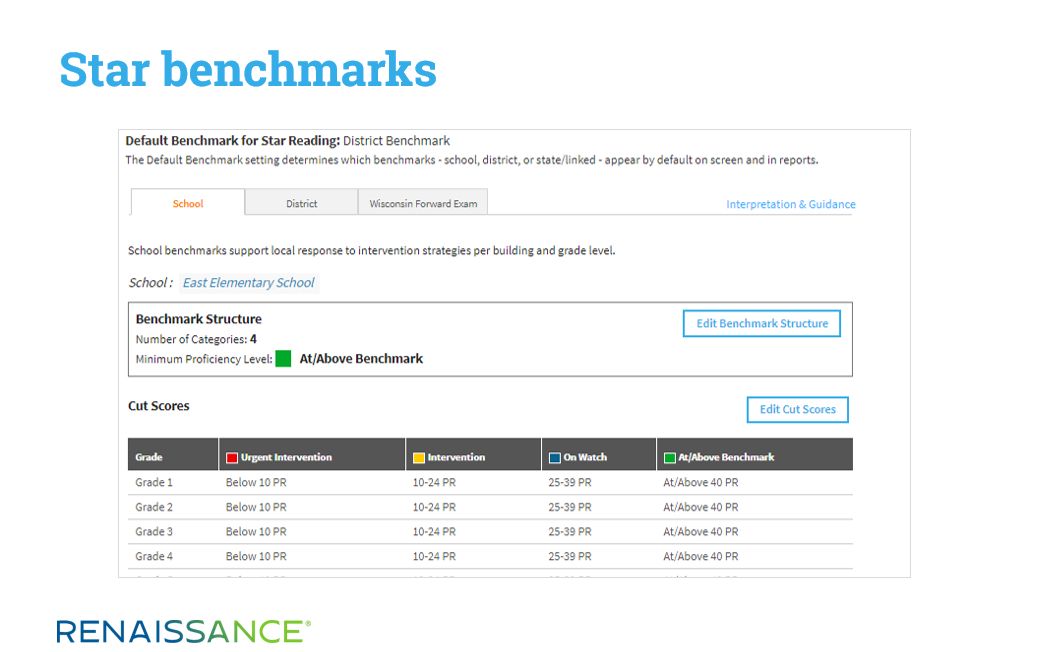

Star Assessments offer several benchmark options to choose from, including default percentile-based benchmarks, benchmarks tied to state-proficiency projections/your summative test, and custom benchmarks defined by your district.

Even though the 2019–2020 school year was disrupted and lower levels of student performance are predicted, we highly discourage the changing of benchmarks for 2020–2021. While keeping existing benchmarks in place may result in higher numbers of students below your proficiency targets, it is best not to look at data through the rose-colored glasses that lowered benchmarks would offer. Leadership guru John Kotter (1996) notes that “without a sense of urgency, people won’t give that extra effort which is often essential.” The lowering of a benchmark can quickly lower the sense of urgency, and we need to feel great urgency about addressing any unfinished learning and the “COVID-19 Slide.”

Also, to date, no states have changed their performance expectations in light of the pandemic, so we still have the same levels of performance expected of our students.

Promoting equity and access

Perhaps the most profound change that we’ll face in the new school year is the manner in which we deliver services. While many states and districts will attempt to conduct a “normal” school year—meaning, kids will be physically present in school buildings—this may not always be possible. Some students and staff members have health conditions that make returning to buildings challenging at best. At the other end of the spectrum, many parents and guardians depend on the custodial assistance that schools provide, because their jobs do not permit or allow them to work from home. Their kids must have somewhere to go. Larry Ferlazzo (2020) argues that a “hybrid option”—where there is support for face-to-face instruction, remote delivery of instruction, and a combination of the two—is “the only solution that…works” in the era of COVID-19.

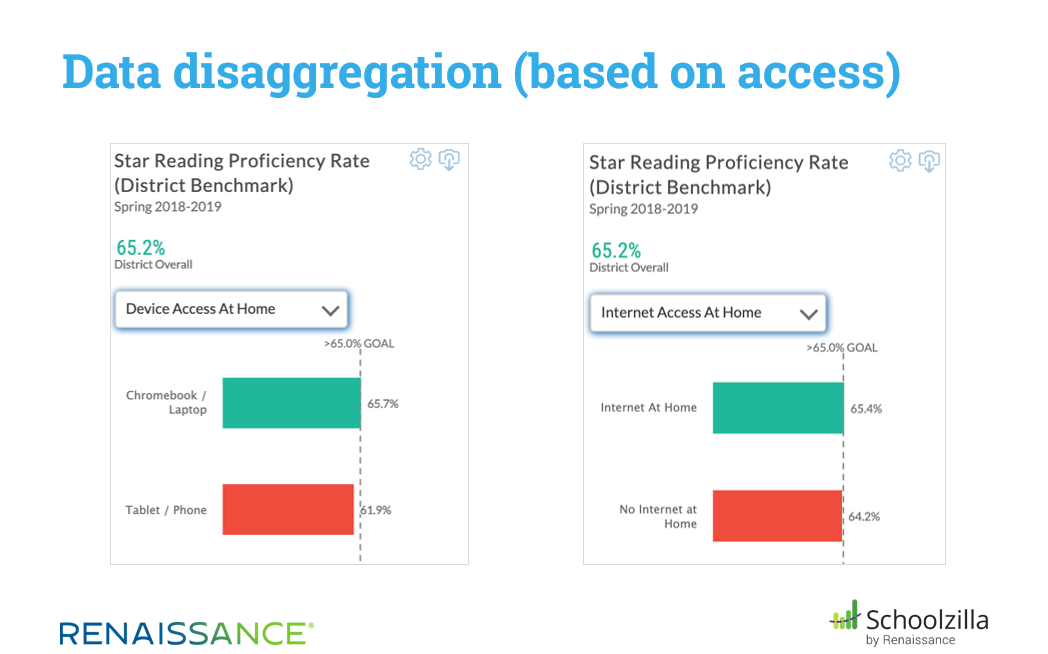

This creates a never-before-seen dynamic. We could, conceivably, have students in the same district receiving services through three different modes of delivery this fall. While most schools only had one mode of delivery this spring—typically remote/online instruction—we are deluding ourselves if we think that services were received uniformly. In some households, each individual has a personal device for online access. In other homes, everyone might share a single device, or there might not be any. Similarly, connectivity capable of streaming content nonstop to multiple devices is the norm in some homes, while others depend on community hotspots that may or may not be physically close to their homes. Still other households have no internet connection at all.

This creates an entirely new need for data disaggregation. For this very reason, an upload of custom demographics is now available in our Schoolzilla data-visualization platform that will allow you to disaggregate student data based on both access to technology (devices) and connectivity, if you tag students with those demographics in your student information system.

In districts that do not have Schoolzilla, something similar could be accomplished in the Renaissance platform by using the “user-defined characteristics” to indicate students’ access to a device and connectivity at home. The process is a bit labor-intensive, but the insights provided will be worth the effort in terms of monitoring student performance in relation to mode of delivery—and understanding the impact of access (and lack of access) on student outcomes.

Resources to move learning forward

As we conclude this blog series on planning for the 2020–2021 school year, it will serve us well to consider what has changed and what hasn’t. The primary change—as mentioned above—is the mode(s) in which we’ll likely deliver instruction. In terms of what hasn’t changed, we’ll still have students who are performing below benchmark, and we’ll still encounter gaps in student learning. We’ll still have the need for valid and reliable interim assessments, for quality formative assessment tools, and for the direction that decision-making frameworks like RTI and MTSS provide.

You’ll still be able to rely on Star Assessments for actionable insights on what your students know, what they’re ready to learn next, and which skills are absolutely essential for moving learning forward.

And, of course, there still won’t be a finish line.

In the new school year, we’ll continue to run the race, but we may also see the start of something new. It’s very possible that we’ll see more and more people coming out to support us. The past several years have seen record low morale among teachers, particularly in public schools. Weighed down by decades of high-stakes accountability requirements and increasing societal pressures, the teaching profession has seen declining entrances and accelerating exits.

But COVID-19 has caused many parents and guardians to re-think the value of school. They found, when they had to assume a large part of the job, that teaching was much harder than they thought. Then, beyond the academic role of school, they found that they greatly missed the social and custodial aspects that school provides for their children. Having a safe place for kids to go for a major portion of the day so that parents could work was profoundly missed.

As a result of the pandemic, many people have become acutely more aware of the scope of services that schools provide. Our “race without a finish line” continues, but more people are cheering us on, with a new-found appreciation of the true scope of our task.

Our challenge—and also our opportunity—in the new school year is to use this increased support, along with our training, our technology, and our commitment to education, to overcome any obstacle in order to move learning forward.

References

Ferlazzo, Larry. (2020). A superintendent’s thoughts on reopening schools this fall. Retrieved from: http://blogs.edweek.org/teachers/classroom_qa_with_larry_ferlazzo/2020/05/a_superintendents_thoughts_on_re-opening_schools_in_the_fall.html

Kotter, John. (1996). Leading change. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Learn more

Are you up to speed on everything Star has to offer? Explore the full suite, including Star Custom, the new Star CBM, and Star Assessments in Spanish.