August 27, 2020

Note: This is the third and final blog in a series on assessment’s “new normal.” To read the previous blog in the series, click here.

In 1948, a local school district in a medium-sized town partnered with a private, home-based school for students with specific learning needs. We don’t often hear about partnerships like this one, but the local school leaders saw this as the best way to address the needs of children in their community who had developmental and/or speech delays. This was their way of promoting equity.

The Grace White School focused on early learning in literacy, mathematics, and music, with a strong emphasis on elocution (speaking clearly and with eloquence). In Kindergarten and grade 1, children thrived as they learned alongside their grade-level peers who were learning at the typical pace. In its 11 years, the school expanded to K–3, and it added learning Spanish to the curriculum beginning in grade 1.

Like most children in a primary-school setting today, students enrolled at the Grace White School were assessed to understand their readiness for Kindergarten and for reading. The assessment data was used to identify strengths and address readiness gaps—a rather modern approach for a school of that time. As we begin the 2020–2021 school year, in whatever form it takes, we must include a similar means of understanding who is ready to learn grade-level content and who requires scaffolding—along with who might need “just-in-time intervention” through additional work with prerequisites. This is what we mean by the phrase equitable access.

Start with screening

From an instructional perspective, screening is among the first steps in providing equitable access to meaningful instruction. Screening is, in some ways, an avenue for learners to elocute what they know and what they’re ready to learn. Their data speaks with clarity. The previous blog in this series examines a trend of foregoing fall screening this year in order to focus more intently, and immediately, on instruction. However, if we set aside screening for the sake of instruction, we’re not only building the plane while we’re flying it—we’re also flying without critical navigation systems to help us gauge where gaps exist and who needs the greatest level of scaffolding and support.

Further, and perhaps more importantly, we’re flying without access to each student’s voice—that is, their story within the data. For some students, however, finding their voice among the data could be a bit more challenging, because they may need to be assessed in unique ways. This highlights the need for truly equitable assessment.

Several years ago, Renaissance announced our intention to develop the Star Assessment suite into the most comprehensive K–12 assessment offering available. Our goal is to systematically build a collection of associated tools and resources designed to meet the needs of as many learners as possible, and this fall brings the delivery of several major additions designed to tell each learner’s story.

Star CBM: Supporting early learners

First, we’re thrilled to announce the release of Star CBM, which brings a set of curriculum-based measures for reading (grades K–6) and mathematics (grades K–3) into the Star family. Despite the power and precision of our computer-adaptive Star tests, we’ve had multiple requests from schools and districts for CBMs. This particular form of assessment provides a more direct and intimate form of assessing students that fits organically into the dynamics of the early grades. It also helps educators assess their youngest learners—either in-person or remotely—on specific and highly predictive readiness indicators.

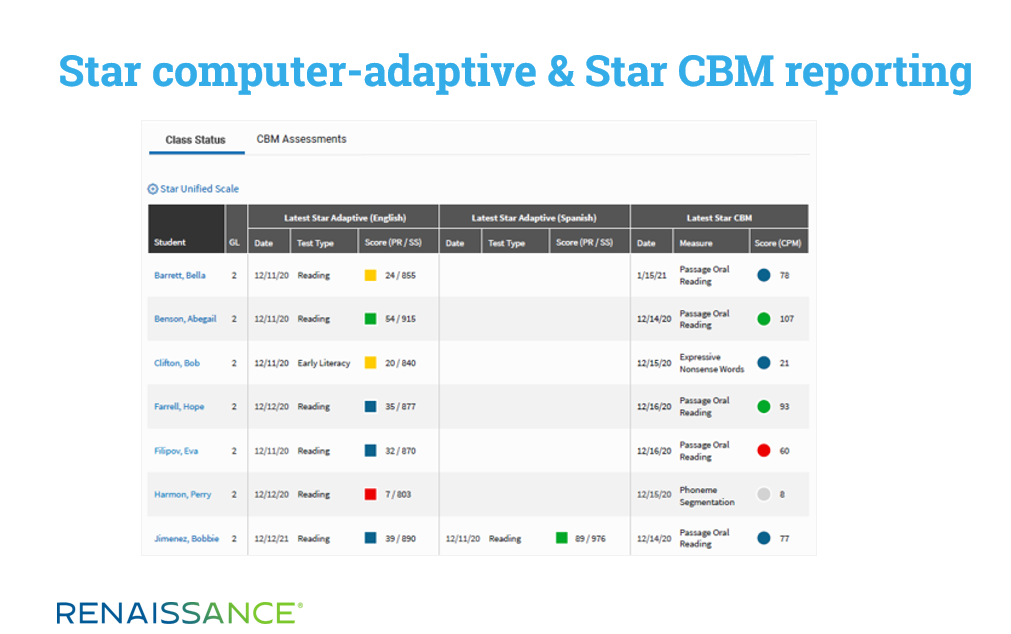

Beginning this fall, educators will be able to view Star CBM data for both reading and mathematics alongside data from Star Early Literacy, Star Reading, and Star Math. As shown below, this provides a more comprehensive and robust understanding of each student’s early learning readiness story.

Star in Spanish: Showing what students know

Equitable assessments help us to find each student’s story among the data. However, for students whose home language is Spanish, screening with English-language assessments may only represent one side of the story. Equity is furthered when Spanish-speaking students have the opportunity to show what they know and are ready to learn in the context of how literacy is acquired in their home language.

Assessment that addresses only the reading skills associated with English may not allow students to fully demonstrate what they know and can do. Historically, emergent bilingual students have been overrepresented in remediation programs and underrepresented in advanced programs, due in part to ineffective and inconsistent methods for identification (Krings, 2017). Quite literally, their voices are muted and their data stories are incomplete.

This fall, we’re proud to release updated versions of Star Early Literacy, Star Reading, and Star Math in Spanish. In doing so, we offer opportunities for emergent bilingual students to demonstrate—precisely—what they know. Star Early Literacy Spanish and Star Reading Spanish assess each learner’s growing ability to read in Spanish. Star Math Spanish highlights students’ strengths in mathematics, and—like all Star Assessments—identifies the skills students are ready to learn. For students whose home language is Spanish, Star Assessments offer the avenue to elocute what they know and can do.

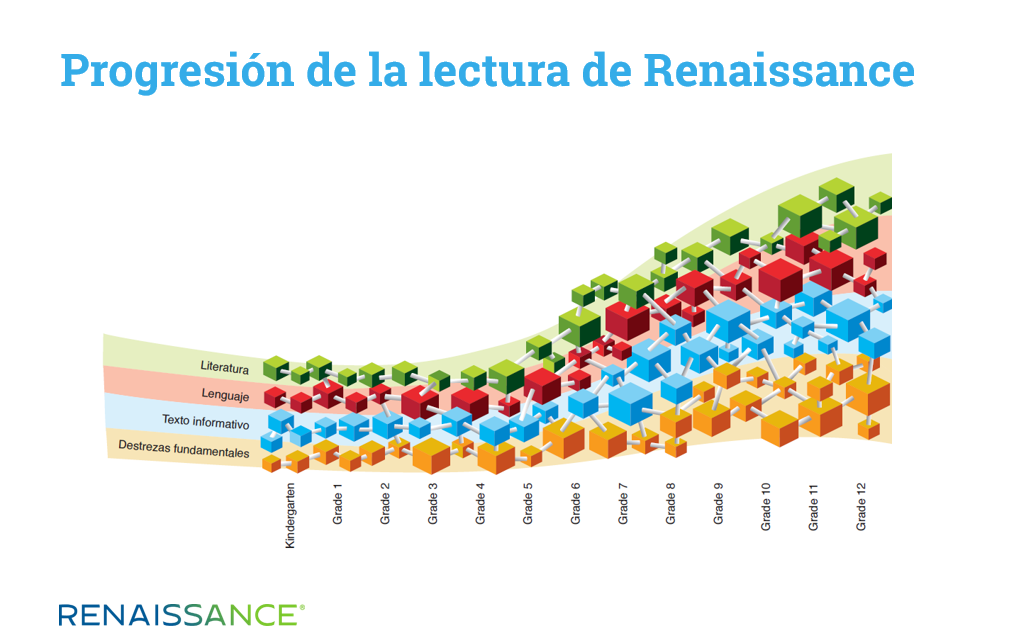

Renaissance content specialists, researchers, and noted external experts have also developed the Progresión de la lectura de Renaissance (Renaissance Reading Progression). Like our English-language learning progression for reading, the Spanish-language progression identifies the skills a student needs in order to achieve success in Spanish reading across grades K–12, as represented in this graphic:

Not only do we hear students’ voices via their Star Assessments data, but the learning progressions make clear where their voices are ready to grow, equitably in Spanish and English.

Schoolzilla: Showing unique data stories

So far, we’ve looked at equity through the lens of early learners and emergent bilinguals. In each discussion, we’ve focused on addressing equity needs when they’re vividly apparent to us, but sometimes needs are not as easily perceived. District leaders may not be aware of opportunity gaps because these gaps may simply not be visible.

The partnership between the Grace White School and the local school district established a means to support all learners in an “in-person” model. This school year, we require that model and one to support all learners in a virtual environment. While access to learning tools (e.g., devices and connectivity) is perhaps the most obvious barrier associated with distance learning, the well-being of both in-person and online learners is of even greater importance.

In too many schools, elements of students’ data stories exist in disconnected and disparate places. The student information system (SIS) holds parts of the story (e.g., demographics and attendance data). The assessment suite holds other critical pieces (e.g., performance and growth), as do various components of curriculum and practice. But too often, no single system allows information to be brought together to tell a cohesive story. Under these dynamics, district leaders can remain unaware of equity issues located just beneath the surface.

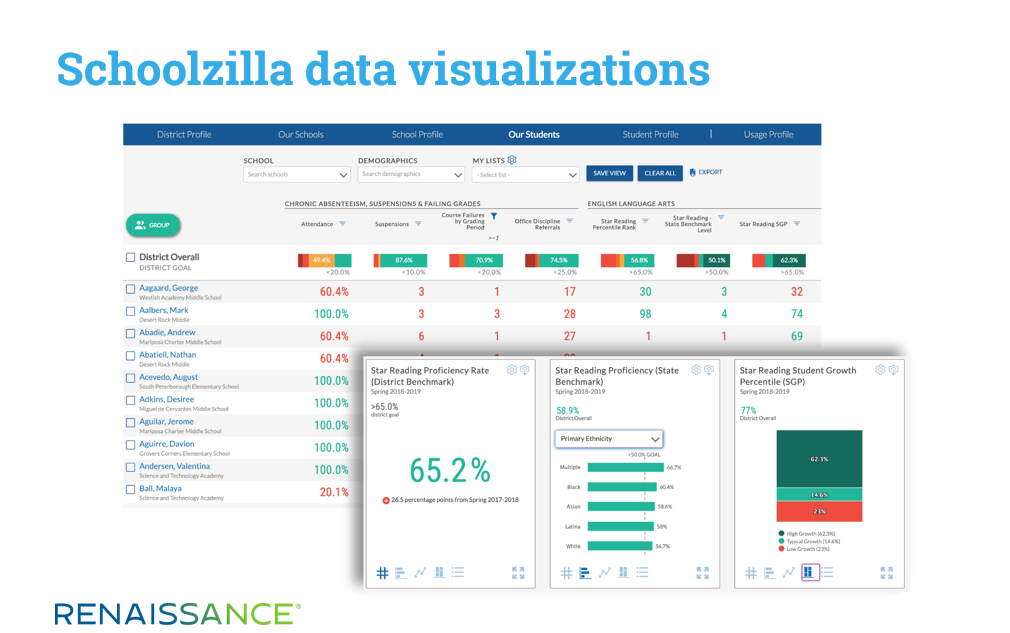

Schoolzilla, our interactive data integration and visualization platform, brings together information from often-disconnected sources. School and district leaders can use Schoolzilla’s data visualizations to explore data from multiple sources in order to uncover hidden equity gaps. Visualizing screening data is critical, especially when you’re able to view this data in the context of other indicators, such as attendance, past course performance, and history of growth.

Visualizing data enables stakeholders to answer essential questions, identify bright spots, and highlight and monitor areas of concern. This is an important process in any school year. This year, it’s made even more critical by the equity gaps related to the availability of digital devices in the home and the reliable connectivity required to interact with teachers and peers, as well as access to learning tools. Considering student achievement in the context of both academic and other data sources builds a more complete—and more equitable—story of each learner, each school, and the district as a whole.

“The vocabulary of conviction”

As Pfeifer (1994) recalled, Grace White directed all those associated with her school to remember that the child is an individual, a person (her emphasis), who needs to develop mentally, socially, emotionally, and physically. She believed that elocution offered students opportunities at school and throughout their lives. She continually referenced the “vocabulary of conviction,” describing it in this way:

“When they can hear it, and speak it, and read it, and write it, they will understand it—literature, history, calculus, physics. And they will be anything they want to be.”

White was passionate that her students would confidently present themselves, engage in meaningful discussions, share ideas, actively support all members of the learning community, and question what they see around them with clarity and eloquence. This became their voice, their “vocabulary of conviction,” used to author their unique stories.

This school year, let us confidently present ourselves with clarity and eloquence as we engage each learner in assessment designed to identify strengths in hand, and strengths ready to be nurtured. Let each district establish its “vocabulary of conviction,” grounded in the language of equitable access to learning and opportunity. Let leaders—at the district, school, and classroom levels—make every effort to hear each learner’s data story, speak about these stories, read them often, and write about them, so that all learners have the opportunity to be anything they want to be.

References

Krings, M. (2017). English-language learners may be over-represented in learning disabilities category. Retrieved from https://phys.org/news/2017-02-english-language-learners-over-represented-disabilities-category.html

Pfeifer, J. (1994). Amazing Grace: An address to education leaders in Abilene, TX.

Learn more

Are you up-to-speed on everything that Star Assessments have to offer? Learn more about Star curriculum-based measures, Star Assessments in Spanish, and other features that will help you to accelerate student learning this year.