September 1, 2020

Recently, there’s been a lot of chatter about the role of assessment in the new school year. Should we or should we not assess students this fall? If so, in which ways?

The title of a recent article in the Washington Post caught my eye: “Why teachers shouldn’t give kids standardized tests when school starts.” While I agree with this statement in a general sense, the article goes far beyond a discussion of standardized summative tests. In fact, it argues that even standardized interim tests will not be useful in addressing students’ needs this school year. In essence, the author presents formative assessment as the be-all and end-all, creating an unnecessary and unhelpful dichotomy between tests that are “formative” and those that are “formal,” and ultimately claiming that only formative assessments have value in the current climate.

Many educators, myself included, have been pushing for more applications of formative assessment for years. I co-authored a book on the topic and have personally trained thousands of teachers on formative classroom strategies. The research base documenting the relationship between formative assessment strategies and student growth is extensive. There has been every reason to “push the pendulum” here—but it is possible to push things too far.

For all our references to pendulum swings in K–12 education, we must acknowledge that the only swings that are truly useful are those that actually power the clock. Life is typically far more about balance than it is about being on the far edge of a continuum. Is there truly no role that formal assessment can play during the 2020–2021 school year? Of course there is—a role that formative assessment simply cannot fill.

Why formative data is not enough

Dismissing all “formal” tests in favor of formative tools is both naïve and does not acknowledge the critical information these tools provide. Rick Stiggins (2017)—who’s one of the most powerful advocates of formative assessment—notes that the “perfect” assessment system is one that meets the needs of all stakeholders, from the state superintendent all the way down to the student who’s just beginning Kindergarten. Assessment, after all, “is the process of gathering evidence of student learning to inform educational decisions,” and different stakeholders need information that takes different forms and is provided by different types of assessments.

When it comes to students as consumers of assessment information, it’s true that formative tools are the best choice. There’s very little (if any) information coming from summative assessments that meets students’ ongoing needs as stakeholders. Once we move beyond students, however, every other stakeholder throughout the system draws something from more formal tests that formative tools cannot provide.

While a teacher is regularly concerned about and guided by the “minute by minute and day by day” information gathered formatively, she also needs normative information to provide the larger context around growth and achievement. For example, a formative assessment can certainly document a student’s mastery of a given skill. However, if it takes the student six days of instruction to acquire a skill that most students master in one or two days, then the “growth” depicted by the formative feedback is incomplete. The fact that the student has learned the skill must be considered within the larger context—namely, that the rate at which he did so was far slower than most others. So, while he “grew” by learning the skill, he actually fell further behind by taking so much time to do so. These sorts of dynamics are detected over time, but only through the use of more formal assessments.

Understanding stakeholders’ unique needs

Collecting information on relative growth connects directly to Response to Intervention (RTI) models. These models are designed to determine whether students are responding to the level of “intervention” they’re receiving, whether this is general instruction (Tier 1), mild-to-moderate intervention (Tier 2), or moderate-to-intensive intervention (Tier 3). RTI models and a similar construct, Multi-Tiered Systems of Support (MTSS), require information on relative performance and growth. Even curriculum-based measures (CBMs), which look and feel more formative in nature because of their design, include information on growth rates and norms. These are important data points that only formal assessments can provide.

From this level up (to specialists, principals, superintendents, etc.), it’s apparent how numerous stakeholders require normative information on student growth and performance. As Stiggins (2017) notes, “Schools are institutions supported by communities that are entitled to information about the effectiveness of taxpayers’ investments,” and the type of information they seek—such as percentile ranks and proficiency projections—comes from formal assessments. For example, many school boards will be asking to what degree “COVID-19 Slide” has impacted students and will be eager to know how students are rebounding and growing over the course of the 2020–2021 school year. Normative information will be required in order to answer these questions.

Equity at the forefront

Without formal assessments, equity issues can also go unnoticed—particularly at the moment we find ourselves in today. It’s no accident that RTI and MTSS models, along with regulations around dyslexia screening and grade 3 reading proficiency, require regular screening. Understanding how each student is performing in relation to benchmarks is important for identifying opportunity gaps, and this helps school leaders to make informed decisions about which students will benefit the most from additional services and support. If you don’t have the data that screening provides, it’s difficult to distribute your resources based on students’ specific needs.

The best thinking around screening compares this process to a routine physical exam—a quick, regular “check-up” on key indicators in order to catch possible issues early, before they become major problems. Given the disruption to K–12 education caused by COVID-19, I’d argue the giving every student a check-up this fall is more important than ever.

Just to be clear, I’m not suggesting that schools administer high-stakes summative tests this school year. What I’m definitively arguing is that stakeholders clearly need the normative information on student growth and performance that’s provided through low-stakes (or even “no-stakes”) interim assessments.

The right assessment at the right time

In our book inFormative Assessment: When It’s Not About a Grade (2009), my co-author and I chose “to focus on the function of assessments rather than their form, using the term ‘informative assessment’ because what we are really seeking are assessments that inform teachers and students.” In the book, we noted how a released version of the SAT—the epitome of a summative assessment—could be used formatively. By having students take the practice test, analyze their performance, review the content, and then re-test, the previously summative tool becomes formative. It informs the students.

Dylan Wiliam, whose groundbreaking meta-analysis “Inside the Black Box” (2010) is the basis for much of the current interest in formative assessment, frames this discussion from the perspective of time. In his view,

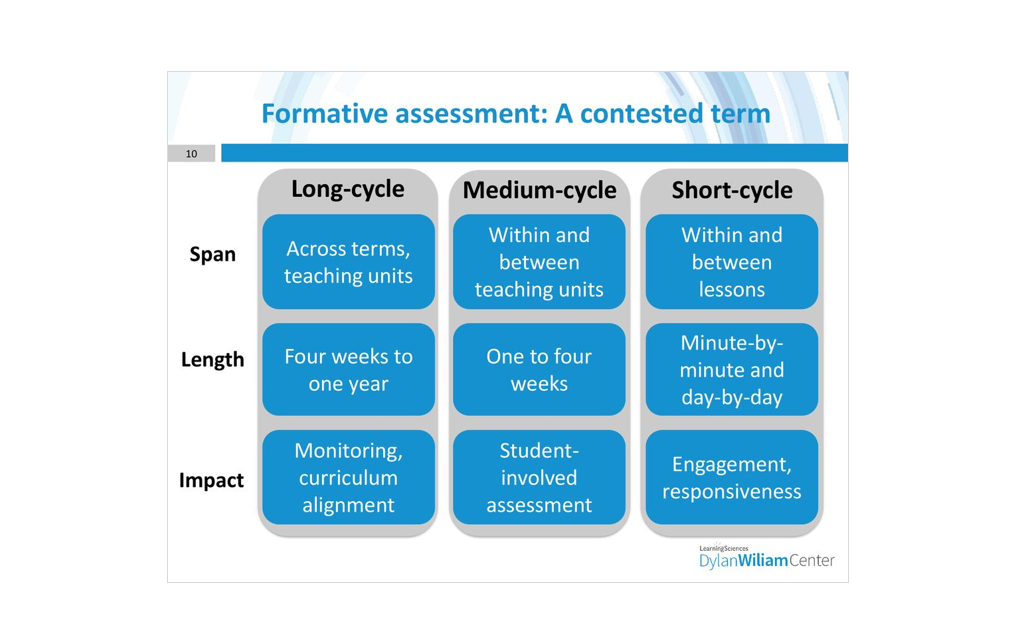

- “Short-cycle” formative assessments are the “minute-by-minute and day-by-day” classroom strategies that are so essential to guiding instruction

- “Medium-cycle” formative assessments are the end of chapter/end of unit tests often developed by teachers to measure the learning that has (or has not) occurred

- “Long-cycle” formative assessments are the more formal tools like Star Assessments that provide normative data—and are often referred to as “interim”

In Wiliam’s model, all three forms of assessment have a clear and critical role to play, as shown in the graphic below. Without long-cycle, formal assessments, overall student monitoring and curriculum alignment cannot occur.

As I noted at the outset of this discussion, the attempt to draw a firm line between tests that are “formative” and those that are “formal” is both misleading and unhelpful. Each category of assessment represents a different tool that provides different—yet equally necessary—data about student learning. In the 2020–2021 school year, we’ll need all three more than ever.

As I noted at the outset of this discussion, the attempt to draw a firm line between tests that are “formative” and those that are “formal” is both misleading and unhelpful. Each category of assessment represents a different tool that provides different—yet equally necessary—data about student learning. In the 2020–2021 school year, we’ll need all three more than ever.

References

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (2010). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment.

Phi Delta Kappan, 92(1), 81–90.

Fogarty, R., and Kerns, G. (2009). inFormative assessment: When it’s not about a grade. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Stiggins, R. The perfect assessment system. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Strauss, V. (2020). Why teachers shouldn’t give kids standardized tests when school starts. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/education/2020/08/03/why-teachers-shouldnt-give-kids-standardized-tests-when-school-starts/

Learn more

Are you up-to-speed on everything that Star Assessments have to offer? Learn more about Star curriculum-based measures, Star Assessments in Spanish, and other features that will help you to accelerate student learning this year.