September 11, 2020

According to estimates, between 60 and 75 percent of the world’s population speak two or more languages. The benefits of bilingualism are well documented: A larger working memory, better reading and listening skills, greater empathy and openness, and expanded job opportunities. Bilinguals are also better at multi-tasking and solving problems, and they generally perform better than monolinguals on standardized tests (Vince 2016; Kinzler 2016; Burton 2018).

In the US, we’ve traditionally looked at emerging bilingual students through the lens of “What don’t they know yet?” and “What do they need?,” which places a lot of emphasis on deficits. In our new webinar, we suggest taking an asset-based approach instead, where we seek to understand what these students know and can do in both languages—and how we can build on this. We focus particularly on students who are learning in Spanish and English, and we explain how you can use Star Assessments to support strong biliteracy.

In this blog, we’ll share several key ideas from the webinar. We invite you to watch the webinar recording for a more detailed discussion of these points—and to learn about our own experiences as bilingual learners.

An important change to our perspective

Moving from a deficit- to an asset-based approach to learning is not a new idea. For example, in 2008, García, Kleifgen, and Falchi argued that English Language Learners are actually emergent bilinguals, functioning in both their native (or home) language and in English, their new language and that of school. Ignoring these students’ home language, they add, perpetuates inequalities in education, discounts the cultural knowledge and understandings this student population brings to the classroom, and incorrectly assumes they have the same needs as monolingual learners.

A number of organizations have embraced this view. The Council of Great City Schools (2017), for example, points out that students’ home languages are “key resources” that “can help them in developing both the social and academic registers of English. Students benefit academically when their home cultures and languages are recognized as assets.” The WIDA Consortium (2014) takes a similar view, stating that “all children bring to their learning cultural and linguistic practices, skills, and ways of knowing from their homes and communities. [The] educator’s role is to design learning spaces and opportunities that capitalize on and build upon these assets.”

Perhaps the most persuasive argument for an asset-based approach comes from a longitudinal study by Thomas and Collier (2017), which we discuss in detail in the webinar. These authors reviewed more than 30 years of student performance data to determine which language programs produce the best (and the worst) results. Not surprisingly, dual-language programs that build upon students’ knowledge and skills in their home language are the most effective at closing achievement gaps between emerging bilinguals and native English speakers. English-only programs, which largely discount students’ home language, are the least effective.

These and similar findings have had a major impact on the work we do at Renaissance. In 2016, we released Spanish-language versions of our computer-adaptive Star Reading, Star Math, and Star Early Literacy assessments. Like their English-language counterparts, these Spanish versions of Star identified the skills that students had mastered. This is obviously important information to have, especially for pinpointing the skills a student has learned in Spanish that can be transferred to English—such as identifying key ideas and details in reading, or multiplying and dividing fractions in math.

However, we realized that Star could be enhanced to also provide detailed instructional planning information in Spanish—which would better meet the needs of the many bilingual and dual-language programs across the US. So, we challenged ourselves to adopt a more asset-based approach, with the goal of achieving parity between Star Assessments in Spanish and in English.

This has been the focus of our work over the last 18 months or so, and this work will continue into 2021 and beyond. But we recently reached the position where we could, so to speak, relaunch our Spanish-language Star Assessments, and we’re excited to share the new features with educators.

Supporting literacy in two languages

The English-language Star Assessments are built on detailed learning progressions for reading and math, which list the skills across grades K–12 that students must master for college and career readiness. Renaissance has created learning progressions for all fifty US states (plus Washington DC), to ensure the progression of skills matches the sequence and organization of each state’s learning standards.

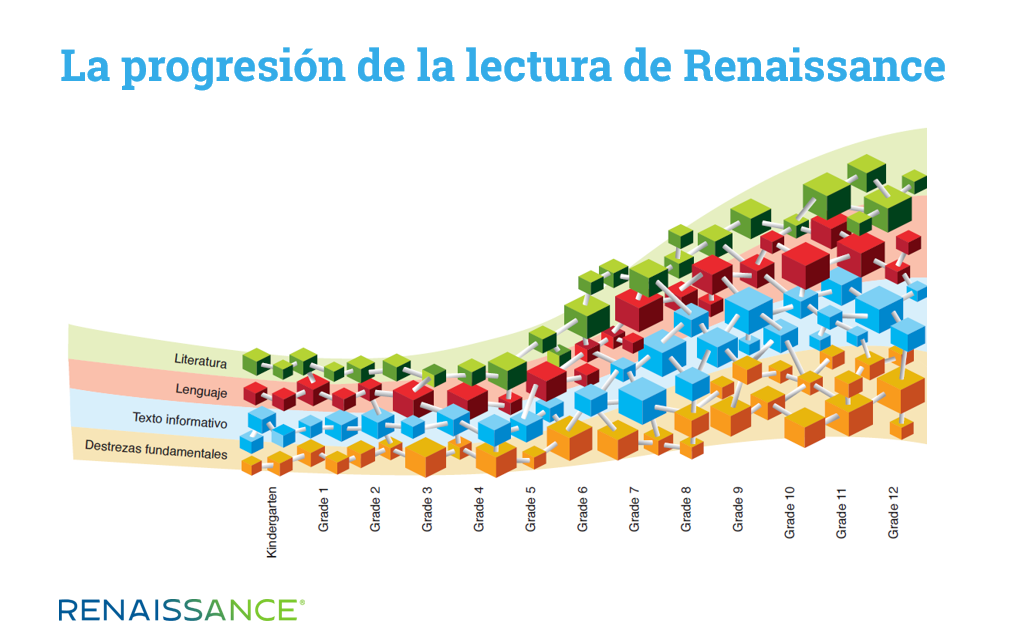

In August, we were thrilled to become the first K–12 assessment company to release an authentic learning progression for Spanish. La progresión de la lectura de Renaissance shows you how literacy develops in Spanish across grade levels and domains, as represented in this graphic:

Each skill in the progression (represented by the different cubes) is placed in a sequence to show when it could sensibly be taught in relation to all the other skills intended for that year. Skills were first ordered based on how students would typically be expected to learn them. To determine this order, we analyzed a variety of Spanish reading standards, including the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (TEKS) in Spanish; the CCSS en Español; the California CCSS en Español; and standards from Puerto Rico, Mexico, Chile, and Peru.

This ordering of skills was then validated by an external reviewer, and by using data from thousands of administrations of Spanish-language Star Assessments. The final order is a suggested sequence and provides context for where students are in their Spanish literacy development. Just like the English progression, this new Spanish progression is a valuable tool in helping educators to answer the question: What’s next?

Connecting assessment to instruction

To illustrate how this new Spanish learning progression might impact day-to-day teaching, let’s consider a student named Carla. As we explain in the webinar, Carla is a fourth-grader in a dual-language immersion program—a program whose goal is biliteracy. Carla recently took the Star Reading assessment in both English and Spanish. (We should note here that Star supports in-person and remote administration, and is well-suited for distance- and hybrid-learning environments. Students typically complete a Star Reading assessment in about 20 minutes, meaning that it’s possible to administer both the English and Spanish assessments in a relatively short period of time—although we don’t recommend administering the two assessments back-to-back.)

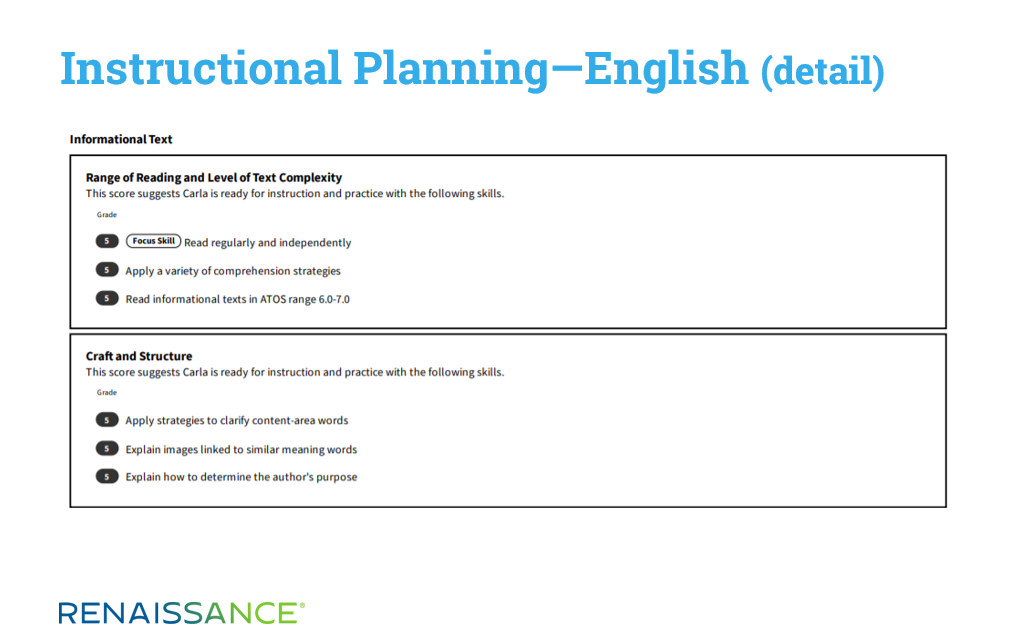

The results of the English assessment show that Carla is performing slightly above grade level. Her Instructional Planning Report lists the literacy skills she is ready to learn in English, based on the learning progression for her state (in this case, Wisconsin):

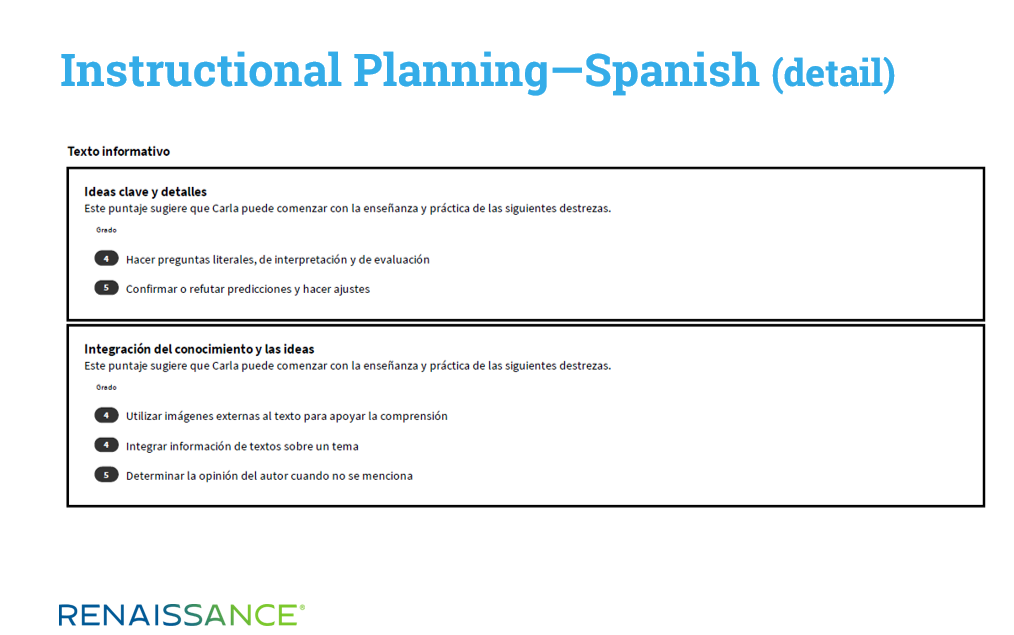

Now let’s turn to the results of Carla’s Spanish assessment. Once again, she is doing quite well, performing slightly above grade level. Here, the Instructional Planning Report lists the literacy skills she is ready to learn in Spanish, based on la progresión de la lectura de Renaissance:

We have several comments here:

First, we should note that educators can run many of the Star Spanish reports in both Spanish and English. They might choose to run the reports in English when they need to share performance and instructional planning information from the Spanish assessment with colleagues who are more comfortable working in English.

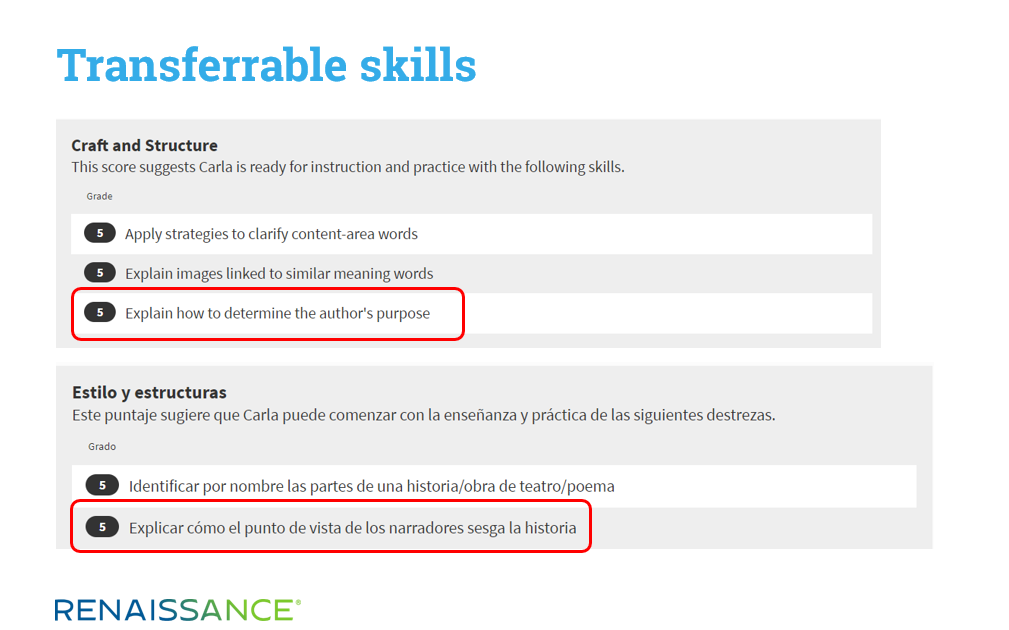

Second, note that Carla’s reports have skills in common—in other words, transferrable skills. Granted, this won’t always be the case, given that each language has unique skills that don’t apply to the other. (Examples: Recognizing onset and rime in English, and recognizing accent marks in Spanish.) But there are also commonalities, as we can see from these report extracts:

Carla is ready to learn two very similar skills. In English, it’s Explain how to determine the author’s purpose, which is a grade 5 skill in the learning progression for the Wisconsin Academic Standards. In Spanish, it’s Explicar cómo el punto de vista de los narradores sesga la historia, which is a grade 5 skill in la progresión de la lectura de Renaissance. In this scenario, Carla’s English and Spanish Language Arts teachers will likely want to collaborate on teaching this skill, since there’s no need to start “from scratch” in each language.

This raises an obvious question: What role does Star Reading in Spanish play in English-only programs? We discuss this point in detail in the webinar, giving the example of a student named Jim, who’s a newcomer to the US and who struggles on the English version of Star Reading. Administering Star Reading in Spanish will identify the literacy skills that Jim has already secured. This will provide a more complete picture of what Jim truly knows, helping his teachers decide where to focus instruction.

Celebra lo que saben

In this blog, we’ve only skimmed the surface of what Star Assessments have to offer, and we invite you to watch the webinar for an in-depth discussion of each of these points. We’re also working on other new resources to support educators’ use of Star in Spanish, including a detailed white paper on the development of la progresión de la lectura de Renaissance. In the meantime, we invite you to explore Star in Spanish and all of the new features—including student growth percentile (SGP) scores to help you measure growth. And, as we mentioned earlier, we have additional features in development for the coming months, to ensure that Star continues to provide tools and resources to accelerate learning for all.

References

Burton, N. (2018). Beyond words: The benefits of being bilingual. Retrieved from: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/hide-and-seek/201807/beyond-words-the-benefits-being-bilingual

Council of Great City Schools. (2017). Re-envisioning English language arts and English language development for English Language Learners. Retrieved from: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED588760.pdf

Garcia, O., Kleifgen, J., & Falchi, L. (2008). From English Language Learners to emergent bilinguals. Equity Matters: Research Review 1.

Kinzler, K. (2016). The superior social skills of bilinguals. Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2016/03/13/opinion/sunday/the-superior-social-skills-of-bilinguals.html

Thomas, W., & Collier, V. (2017). Validating the power of bilingual schooling: Thirty-two years of large-scale, longitudinal research. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 37, 1–15.

Vince, G. (2016). The amazing benefits of being bilingual. Retrieved from:https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20160811-the-amazing-benefits-of-being-bilingual

WIDA. (2014). The early English language development standards. Retrieved from: https://wida.wisc.edu/sites/default/files/resource/Early-ELD-Standards-Guide-2014-Edition.pdf

Ready for more insights on assessing emergent bilinguals? Watch the webinar for tips and best practices for using Star Assessments in Spanish to support bilingual learners.