April 16, 2021

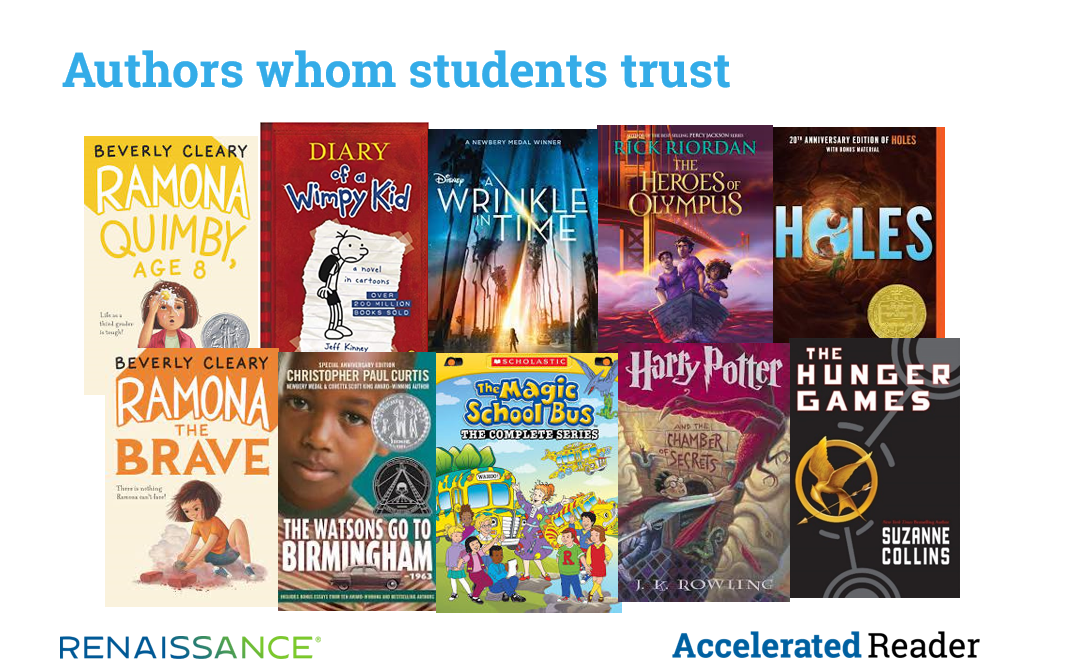

With the recent passing of Beverly Cleary, we lost a giant in children’s literature. She is among a small, select group of authors whom massive numbers of children just seem to trust. That is rather magical. Cleary’s adventures of Ralph S. Mouse (Runaway Ralph and The Mouse and the Motorcycle), Ramona Quimby, Henry, Beezus, and others are perennial favorites. Along with series like Diary of a Wimpy Kid, Percy Jackson, Harry Potter, and The Hunger Games, Cleary’s novels are widely read, year after year.

The appeal of Beverly Cleary is also part of Renaissance lore. Don Peak, who was one of the first and most successful principals to oversee an implementation of Accelerated Reader in Texas, often told the story of how his son connected with Cleary’s books. This story was so impactful that it was embedded in our AR professional development for years.

Peak’s son was a very capable middle-school reader with a grade equivalent (GE) of 10.0. His first book selection when using Accelerated Reader was Cleary’s Henry Huggins. Believing this book to be too low in terms of readability level, Peak bit his tongue because his son, who previously didn’t read much, was choosing to read. This became harder when the next book choice was Beezus and Ramona. When his son brought home Ribsy, a third Clearly book, Peak “made a beeline to the library” to consult the librarian who had assisted in bringing Accelerated Reader into the school. The story continues in his words:

I asked her, “My son has read three Beverly Cleary books in a row, so what do I need to do?” She gave me a good piece of advice. She said, “You told me he’d never read before and he’s reading now. You don’t ‘do’ anything. You let him read.” Then she said, “Besides, we only have two more Beverly Cleary books in the library.”

So, I left him alone and he read those two other Beverly Cleary books, and then he came home without a book. I said, “You didn’t get a book?” He said, “No, you know I read all of the Beverly Cleary books in the library, but this kid at school told me that they have two more of them at the county library. Will you drive me over there?” Now, I am one who can take good advice, so I said, “You bet. Let’s load up.” So, he read those two Beverly Cleary books and there were no more Beverly Cleary books in our county. The next book he selected to read was Tom Sawyer.

You see, we go through stages of reading. I did. You probably did. At the point where he was—where he found himself and he found that first book, Henry Huggins—he trusted that author and he was not willing to trust any other author. It brought him pleasure, so why not stick with it? And that’s what he did. You’ll see many kids doing this, and I don’t think we need to discourage it.

While many reluctant or struggling readers willingly engage with texts like Diary of a Wimpy Kid and Gangsta Granny, some educators express concern about these choices, just as Peak did. They question the literary merit or the relative reading level of these books, particularly when students who might be a bit older engage with them. But I say, if the choice is between a struggling reader either (a) reading nothing, or (b) willingly engaging with a lower-level text, the choice is clear. As Don Peak’s school librarian advised him, let reluctant or struggling readers read what they want to read, and then work to guide their reading practice from there. Reading something is better than reading nothing.

A first taste of success

For many students, finding pleasure in and truly connecting with reading must begin with finding some success—often their first success in reading. Don Peak’s son was a reluctant reader, not a struggling one, but the point is the same. Consider this story from one of our Renaissance Coaches who regularly delivers professional development around Accelerated Reader:

I had been working with a librarian who was working so hard to get AR set up and running at her school. We had been working together for a while, and one day out of the blue she called me because she had to share what had just happened. She was in the library and a student came up to her and said that she had just gotten a 100 percent on an AR quiz! The student was so excited about the score, because “it was the first time she had ever gotten a 100 in reading. She hadn’t thought she would ever accomplish that.” My librarian friend told me that after talking with the excited student, she went into her office, shut the door, and cried.

Part science, part art

In our guidance to educators on using Accelerated Reader, we have written that “matching students to books remains as much art as science, which is why teachers and librarians are, as they have always been, essential in the teaching of reading.” We add that “no formula can take the place of a trained educator who knows her students. Readability formulas, reading tests, and reading ranges are important tools” because “they give teachers and librarians a beginning—a place to start in their task of matching a student to a book.” But ultimately they are just that: tools. The educator brings the human element and additional considerations about specific students, such as: Are they enthusiastic readers? Reluctant readers? Struggling readers? As Daniel Willingham (2015) points out, “Choice is enormously important for motivation, but there must be teacher guidance” as well. We are always working to strike the right balance between the two.

I was teaching high school at the height of the Harry Potter craze and, for most of my students, the first few books in that series were below their suggested reading ranges. But when students—particularly those who were not generally enthusiastic about reading—approached me with a 400-page book in their hands and earnestly asked, “Mr. Kerns, I know this book is a bit below my reading range, but can I read…?,” the rest of what came out of their mouths generally sounded like the “blah blah blah” of Charlie Brown’s teacher. The last thing I was going to say was “No, you can’t read that.”

While reading formulas and readability levels are useful tools, we sometimes need to lay down the tools and ignore the science of them in favor of the art of knowing the needs of specific students. By all means, push your capable, successful readers to higher-level books when they need to be pushed. But also know when it’s less about pushing students—particularly those who are struggling or reluctant readers—to higher-level books than allowing them to read in order to find success and joy. In other words, manage your students’ independent reading practice—but not too rigidly.

Time spent “just” reading

In our recent book Literacy Reframed, my coauthors and I advise educators to “divide discussions about reading into a few distinctly different categories—reading to students, having students read independently, and reading with students (instructional reading)…[because] different rules govern what constitutes success within each category.” We add that “wide independent reading holds significant, overlooked, and undervalued potential,” yet convincing some people of the importance of regular independent reading time is still a challenge. “How could we possibly allocate so much time to the students just reading?,” these critics ask. Some would prefer that all reading time be reserved for whole-group reading of a common text, with any additional time spent on reading strategies and the lessons of the curriculum.

In fact, one middle-school teacher recently wrote about how he resented the use of school time for Accelerated Reader. He called for this time to be cut from the school day, in order to allow more time for “grappling with complicated narrative structures, idiosyncratic narrative perspectives, enigmatic plots, and multi-faceted characters.” While these elements all have a time and a place—grade-level reading instruction clearly must occur—I contend that students, particularly those who are struggling or reluctant, also need to be able to experience reading as a fluent and pleasurable activity, lest they never find a love of books and reading.

Willingham (2015) remarks that “setting aside class time for silent pleasure reading seems to [him] the best way to engage a student who has no interest in reading,” because “it offers the gentlest pressure that’s still likely to work.” As an educator, I’ve experienced few, if any, instances where whole-class reading experiences turned non-readers into readers. But I can think of many occasions—including those I’ve discussed in this blog—where independent reading experiences have accomplished this.

References

Fogarty, R., Kerns, G., and Pete, B. (2020). Literacy reframed: How a focus on decoding, vocabulary, and background knowledge improves reading comprehension. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.

Willingham, D. (2015). For the love of reading: Engaging students in a lifelong pursuit. American Educator, 39(1), 4–13, 42.

Looking for diverse books to engage your students? Check out the latest edition of What Kids Are Reading, the world’s largest annual study of K–12 student reading habits. And to see everything that today’s Accelerated Reader has to offer, click the button below.