June 4, 2021

In 1996, I was teaching high school in Milford, Delaware—a state that was home to a massive credit card bank called MBNA. The bank created the MBNA Excellence in Education Foundation and was very willing to fund thoughtful grant proposals from teachers. My colleague, Mercedes, and I had both heard about Accelerated Reader, and we were certain that bringing the program to our school would make a positive impact on students.

We stayed late on an early dismissal day and carefully crafted our grant proposal for the AR software, as well as a massive infusion of books for our school library. A few months later, we were unpacking the new books and arranging for professional development for our Accelerated Reader implementation.

Now, implementing AR isn’t unusual, but starting the implementation in a high school is. Most districts begin the program with their elementary grades and later expand to higher grades. In some districts— even those with well-established AR implementations—you might not find AR in the high schools at all. Yet our implementation in Milford made such an impact that within 6 months, AR was rolled out to our middle school. Within 18 months, AR was used in every school in the district.

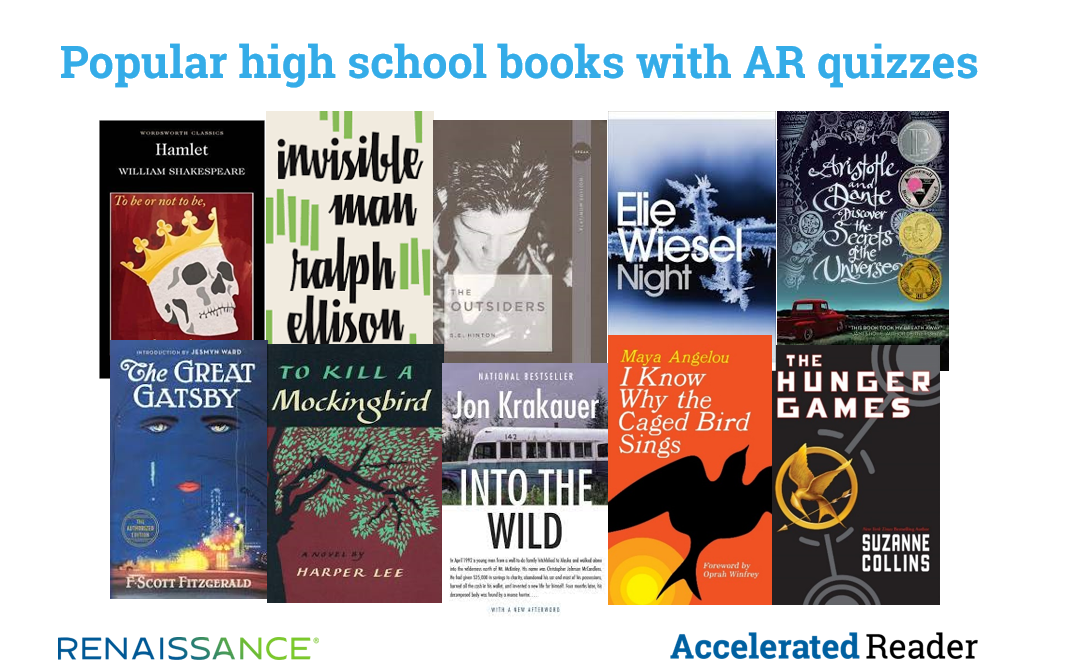

For Mercedes and me, there was never a question of AR’s relevance to high school students. Even a quick review of the book titles supported by AR reveals both classics and the best in new young adult literature. So, why is it that AR sometimes does not continue through all the grades in a district? Why is it that, despite including titles such as Hamlet, Invisible Man, To Kill a Mockingbird, The Great Gatsby, The Hunger Games, and The Outsiders, AR is more often associated with the elementary grades than the secondary ones?

Understanding student reading motivation

I think a primary reason for this is the shifting attitude toward reading as students ascend the grades. Daniel Willingham (2015) notes that “although kids like reading (both at home and at school) in the early grades, their opinions become more and more negative as they get older,” creating the reality that “by high school, the average kid is at best indifferent to reading.” As a result of plummeting motivation, secondary students in most schools read very little—in fact, shockingly little.

When he polled the teachers and parents of teenagers, Willingham found that, on average, they hoped that students were reading roughly 75 minutes a day. But, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics’ American Time Use Survey, “the actual time American teenagers spend reading is 6 minutes” per day (Willingham, 2015). He cautions us, however, that behind this average is the stark reality that “most kids don’t read at all, and a few read quite a lot.”

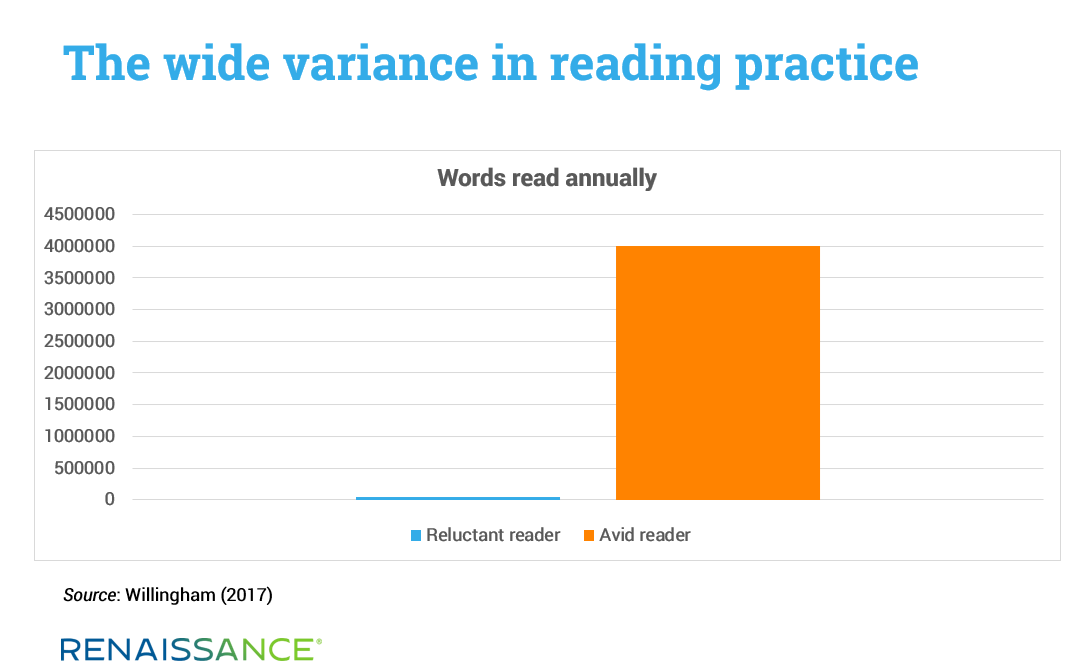

We also see the wide variance in student reading practice when Willingham (2017) notes that while “reluctant readers read 50,000 words each year…avid readers encounter many more words—as many as 4,000,000.” When represented in a graphic format, this difference is eye-opening:

Willingham’s statement echoes a finding by Terry Paul (1992), the co-founder of Renaissance, that the “top 5% of readers read 144 times more than the bottom 5%.”

The benefits of wide independent reading

The impacts of these disparate rates of reading practice are profound. Wide reading supports the development of fluency, the acquisition of vocabulary, and the development of background knowledge. This means that regular readers, who also tend to be the top readers, become even better readers because they read.

The idea that better readers get even better while non-readers fall further behind may evoke associations with “the Matthew effect,” a concept based on the following Bible verse:

For whosoever hath, to him shall be given, and he shall have more abundance:

but whosoever hath not, from him shall be taken away even that he hath.

Matthew 13:12, King James Version

Loosely paraphrased, this verse is familiar to many as the aphorism, “The rich get richer and the poor get poorer.” But, is wide reading—an activity that many high school students choose not to engage in—really an example of the Matthew effect? It’s clearly not the case that massive numbers of students cannot get access to books. Most are not “book poor.” On the contrary, thanks to digital reading platforms, today’s students have easier access to text than any prior generation. As Mark Bauerlein (2008) points out, “Never before have opportunities for education, learning, political action, and cultural activity been greater…. The fonts of knowledge are everywhere, but the rising generation is camped in the desert.”

I think this comparison to a desert is very appropriate. If what we desire is a landscape of wide student reading, we must acknowledge that, in general, the secondary grades are a barren desert into which it is very difficult to introduce new life.

In Raising Kids Who Read (2015), Willingham asserts that we must strive to support all students in having a positive attitude toward reading. He suggests that “one source—probably the primary source—of positive reading attitudes is positive reading experiences. This phenomenon is no more complicated than understanding why someone has a positive attitude towards eggplant: you taste it and you like it.”

He adds that “for many students, ‘reading’ means books written by dead people who have nothing to say that would be relevant to your life. Nevertheless, you are expected to pore over their words, study them, summarize them, analyze them for hidden meaning, and then write a five-page paper about them.” For most students, there is no pleasure in this.

So, how might we better support secondary readers in forming a positive reading attitude through positive reading experiences? Here are four ideas that are applicable to both in-person and remote learning environments:

1. Schedule 20 minutes daily for pleasure reading

First, Willingham (2015) suggests that schools “make reading expected and normal by devoting some class time to silent pleasure reading.” While this is good for all students, Willingham remarks that it “is the best solution [he] can see for a student who has no interest in reading,” because “it offers the gentlest pressure that is still likely to work.”

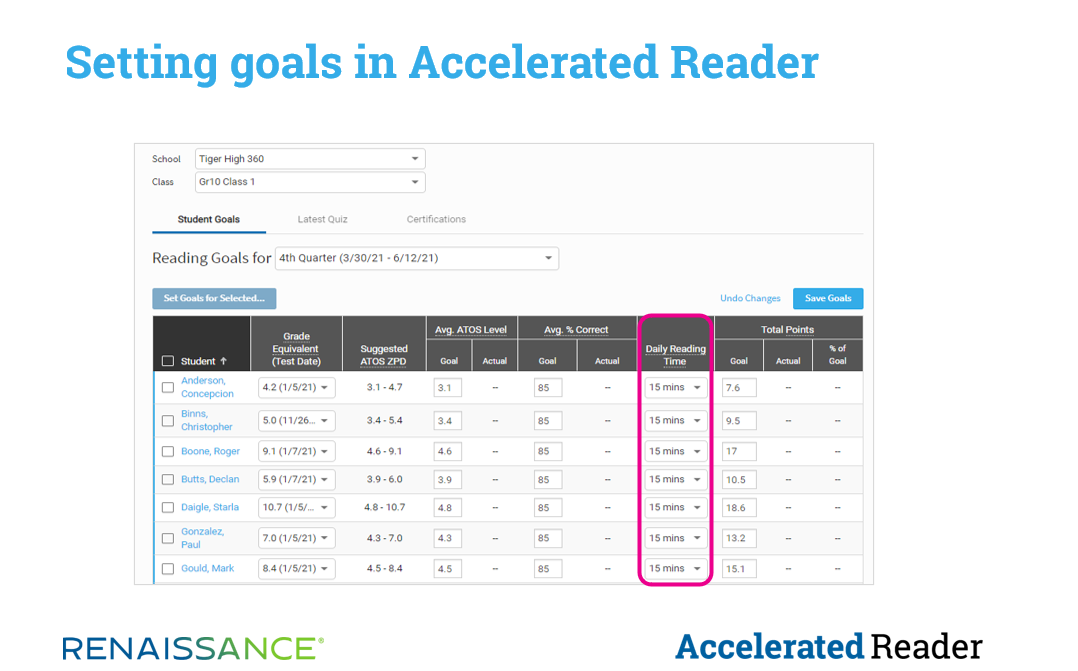

A critical element of making this time optimally successful is the setting of student reading goals, a topic we explored in detail in an earlier blog. Accelerated Reader helps teachers to set personalized goals for students, including a goal around daily reading time. Our research has consistently shown that students who have worked with their teachers and have goals entered in AR demonstrate more growth than students with no goals set.

2. Delineate between academic reading and pleasure reading

When establishing time for pleasure reading, Willingham is direct in his call for educators to delineate between academic and pleasure reading, not only in their own minds but also for students. His “concern is that kids might confuse academic reading with reading for pleasure. If they do, they’ll come to think of reading as work, plain and simple.” While, as teachers, “we’d like to think that academic reading is pleasurable…in most schools, ‘pleasure’ is not a litmus test. Academic reading feels like work because it is work. But pleasure ought to be the litmus test for reading for pleasure.”

Here, student choice in what to read is critical, especially for reluctant readers. With more than 220,000 titles available, almost any student choice is encompassed with the Accelerated Reader quiz collection.

3. Manage reading practice—but not too rigidly

Using “pleasure” as the litmus test has implications. While research is clear that engaging with more challenging texts generally yields the most growth and that reading widely (across multiple topics and genres) is also beneficial, for struggling readers, we must first get them to willingly read. Reading something is clearly better than reading nothing. But if we restrict, push, or direct things too much, we can easily sap the pleasure from pleasure reading.

For example, teachers are often concerned when students choose books that are below their reading level or are perceived as lacking in literary merit. I discussed this point in detail in a recent blog, where I pointed out that sometimes our focus should be “less about pushing students—particularly those who are struggling or reluctant readers—to higher-level books than allowing them to read in order to find success and joy.”

Again, Willingham (2015) and many others note that choice in what to read is very important, because it “allows the greatest possibility that when the reluctant reader does give a book a try, he’ll hit on something that he likes.” He adds, “If my teen avoided all reading, I would be fine with him reading ‘junk.’ Before he can develop taste, he must first experience hunger. The first step is to open his mind to that idea that printed material is worth his time.”

4. Use every resource available

Given the barren “desert” of secondary reading motivation, we must be honest that there is no silver bullet. Motivating and engaging most secondary readers is just plain hard work. In our high school in Delaware, we found that Accelerated Reader was an indispensable tool—not a “silver bullet.”

For us, the massive infusion of new books into the school library was another critical motivator. If your collection is limited and/or older, students are less likely to engage with the titles. A new cover on a classic title can create renewed interest. And you can take simple steps to better display the books in your library, helping them to take on the qualities of a bookstore.

Also, the growing ease of accessing texts digitally can be a powerful motivator. Willingham (2017) remarks that “if it’s affordable, an e-reader is wonderful for instant access,” because we can create a dynamic where books are not “just available, but virtually falling into children’s laps.”

35 years—and counting

This year, we’re celebrating 35 years of Accelerated Reader, which began as a program intended to get a reluctant reader to read. Decades have passed, and educators still keep coming back to the question of how to motivate students to read as much as possible. The enduring nature of this challenge does not mean it’s a lost cause; it’s merely a difficult one—and one that becomes even more difficult as students age.

The difficultly and gravity of this challenge make me think of lyrics from “The Man of La Mancha,” the musical adaptation of Don Quixote. In striving to get every student to read, teachers “dream the impossible dream” and “fight the unbeatable foe.” New tools and insights help us in this quest and— because we know the quest is so important—we’re “willing to march into Hell, for a Heavenly cause.” “And the world will be better for this: That [caring teachers], scorned and covered with scars/Still strove, with [their] last ounce of courage, to reach the unreachable star.”

References

Bauerlein, M. (2008). The dumbest generation: How the digital age stupefies young Americans and jeopardizes our future. New York: Penguin.

Paul, T. (1992). National reading study and theory of reading practice. Madison, WI: Institute for Academic Excellence/Renaissance Learning.

Willingham, D. (2015). Raising kids who read: What parents and teachers can do. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Willingham, D. (2017). The reading mind: A cognitive approach to understanding how the mind reads. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Looking for the most popular books in high school? Check out the new edition of What Kids Are Reading, the world’s largest annual study of K–12 student reading habits. And to see everything that today’s Accelerated Reader has to offer, click the button below.