October 22, 2021

In K–12 education, we often use medical analogies to describe our assessment practices. For example, it’s common to hear the state summative test described as a “post-mortem” on the school year. In contrast, formative assessments are often compared to a physical exam or “check-up,” because they occur earlier in the year and provide information that can be used to save the “patient.” Similarly, the levels of instructional service provided in an RTI or MTSS model have been compared to the medical triage model, directing support where it’s needed the most. Recent articles on the COVID-19 disruptions recommend that we use a form of “instructional triage” to address unfinished learning.

I propose that we add one more analogy to this list. I contend that the recent disruptions to schooling mean that many students have experienced an academic trauma. Data from Renaissance’s How Kids Are Performing report series, for example, show significant impacts in terms of math performance. Overall, students in grades 2–8 were 11 percentile points below pre-pandemic expectations at the end of the 2020–2021 school year. Students in some racial/ethnic groups were even more impacted, performing 18–19 percentile points below expectations. These impacts are clearly significant, and this represents trauma.

Math was not the only affected subject area. The How Kids Are Performing findings indicate that students in grades 1–8 were down 4 percentile points in reading performance at the end of last school year, with some racial/ethnic groups down 7–11 percentile points. Grade 1 students, who had been faring well in the first two rounds of the analysis (Fall 2020 and Winter 2020–2021), suddenly dropped to 7 percentile points behind in the spring.

The analysis even included an estimated number of weeks of instruction that would be necessary to catch students up to pre-pandemic levels of performance. (This is defined as one additional hour of reading or math instruction each weekday, or five additional hours per week.) The findings suggest that, at most grade levels, we might need to find 80–120 additional hours of instruction across both reading and math to reverse the pandemic’s impacts.

While some commentators claim that pandemic-related learning loss is a “myth” or that students are merely “rusty” and will rebound quickly, How Kids Are Performing and similar studies demonstrate that this is not the case. The recent disruptions have unquestionably impacted student performance, and slower rates of growth last school year mean that the situation has become even more dire. Again, this is academic trauma. And in the same way that a physician would closely monitor the vital signs of an individual who experienced a physical trauma, additional monitoring of students’ progress this school year is in order.

So, how might we go about this in a thoughtful and practical way? Let me suggest three options, using examples from Renaissance’s Star Assessments.

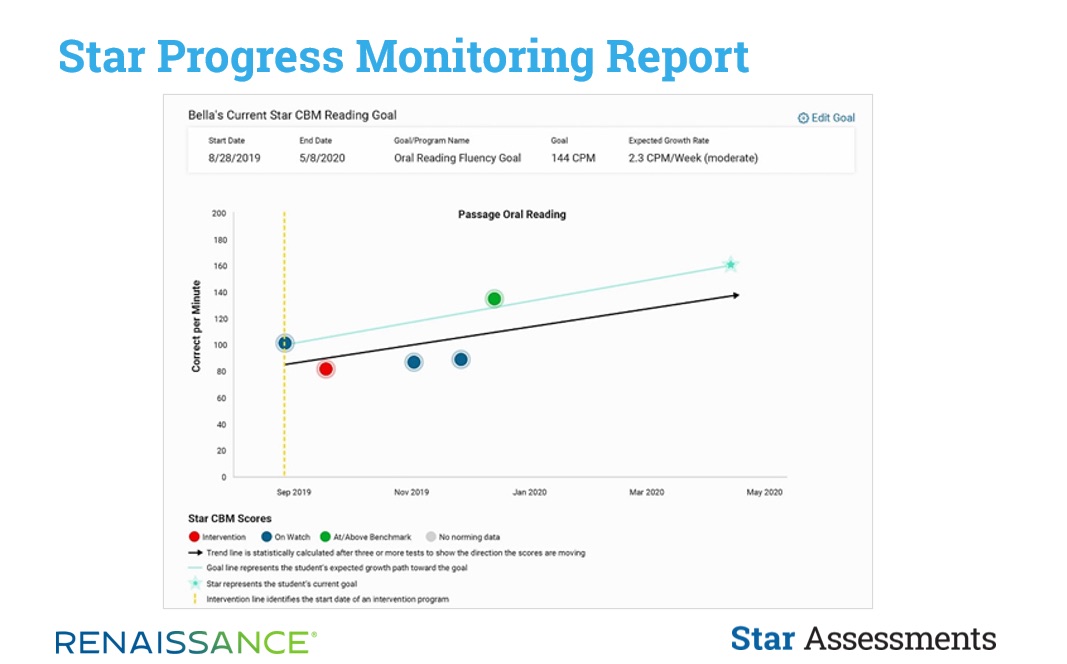

Progress Monitoring Report—for students in intervention

For students who are in formal interventions, this is already addressed. The RTI/MTSS process requires regular Progress Monitoring, which is accommodated through Star’s Progress Monitoring Report. Prior to using the report, teachers or interventionists work through a brief setup process, where a growth goal is established and a name and target end date for the intervention are entered to fully populate the report. (The example shown below is from Star CBM Reading, although the report functions the same way in our computer-adaptive Star Assessments.)

Once students have taken 4 or more Star tests during the course of an intervention, interpreting the report is a relatively straightforward matter of comparing the desired growth rate (indicated by the green goal line) to the growth rate currently being achieved (indicated by the black trend line). In this case, the black trend line—reflecting actual growth—falls below the green goal line, meaning that the student is not responding adequately to the intervention and more intensive services are likely needed.

While this report offers detailed monitoring of progress, only a portion of students will qualify for intervention services. Yet the recent academic trauma has impacted nearly all students. For this reason, we need additional options.

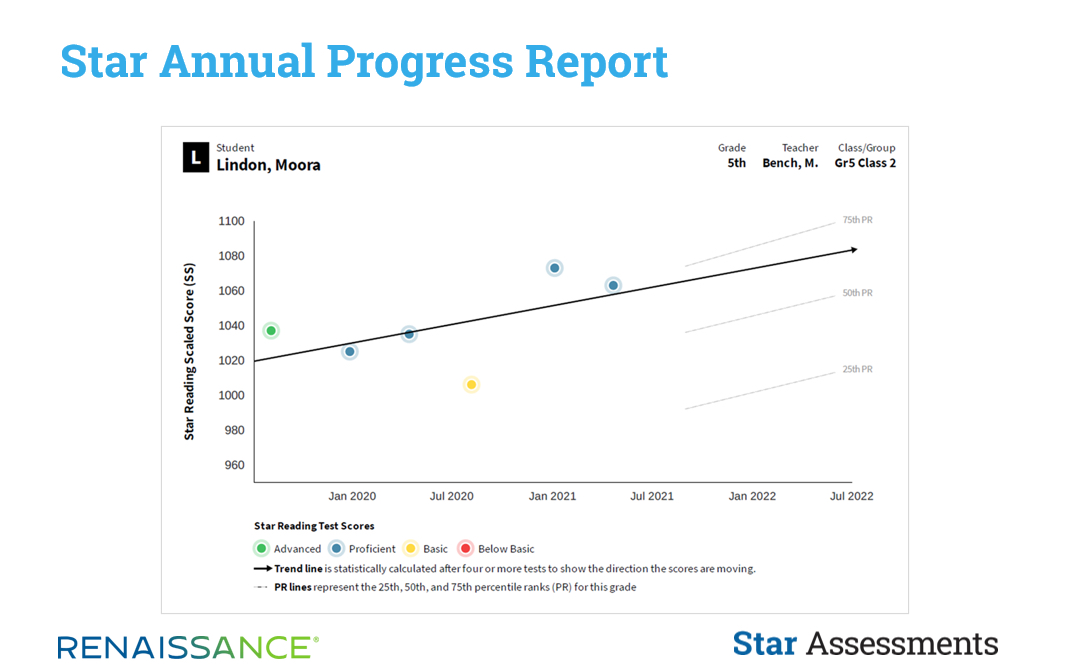

Annual Progress Report—for students with a testing history

For students who are not in formal intervention settings but who have a testing history with Star, the Annual Progress Report is a useful option. While this report requires 4 or more Star tests in order for a black trend line to be generated, these tests can cross academic years. Gray lines indicate the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile ranks (PR) of performance within the current academic year, providing reference points for the rate of growth suggested by the trend line.

In this example report, we see that Moora has 6 tests (reflected by the colored dots) in her testing history. The black trend line depicts her estimated future performance, and the gray PR lines provide additional context. At the current rate, Moora will likely finish the academic year performing mid-way between the 50th and 75th percentile for her grade level.

Depending on which benchmark option your school or district chooses, you will see different names or categories for the dots reflecting each test. Moora’s school has chosen to use a benchmark tied to the state test categories: Advanced, Proficient, Basic, and Below Basic. Of Moora’s 6 tests, we see only one instance where she performed at a Basic level (yellow dot). She generally performs at a Proficient level (blue dots), and once she even achieved a score associated with the Advanced level (green dot) for that point in the school year.

As noted earlier, this report relies on information from prior academic years. If Moora’s current performance is substantially better or worse than in previous years, however, the most accurate read of her performance in relation to the expectations of the current grade level might be found in our final report.

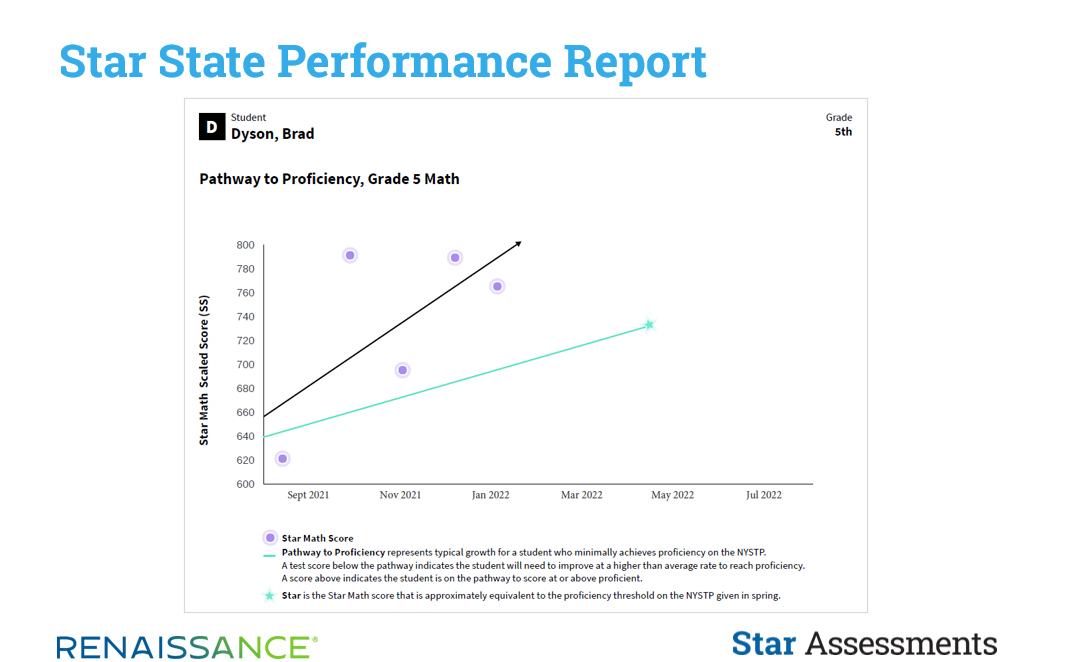

State Performance Report—for focusing on the current year

Like the Annual Progress Report, Star’s State Performance Report involves a statistical linking to your state test, but this report focuses only on the current school year. It is read in a similar way to the Progress Monitoring Report, where the black trend line is compared to the green goal line. In this report, the goal line represents the level of performance necessary to receive a passing score on your state summative test in the spring.

This report requires 3 or more Star tests within the current academic year for a trend line to be generated. As a result, if students only take Star during the traditional fall, winter, and spring screening windows, a trend line will not be generated until spring—which may be too late for progress-monitoring purposes this year.

To address this dynamic, some schools adopt an approach called “3+1,” where the standard screening windows are supplemented with an additional screening that occurs in late fall (e.g., November). This means that the proficiency projections of the State Standards Report’s trend line would be available in January, following winter screening. In addition, the “+1” screening window provides an additional school-wide opportunity to plot students’ performance against important benchmarks, as well as updated instructional planning information.

That said, our general guidance around assessing students with Star is, Do not give the assessment unless you’re planning to review and act on the results. Before adding an additional screening window, consider whether your data teams have the capacity to review the data. If so, then “3+1” is an option. If not, then this is probably not the right solution for you.

An abbreviated option would be a “+1” window for only targeted students, grade levels, or subjects. Given common accountability requirements around grade 3 reading proficiency, for example, and given the disproportionately high number of reading Focus Skills in the early grades, you might choose to add the “+1” screening only for students in grades K–3. You might also limit the “+1” screening to only those students who were below benchmark during fall screening and who were not placed in a formal intervention. The additional screening would help to ensure that these students are not slipping in terms of performance.

Or, given that math performance has been far more impacted than reading, you might choose to forgo an additional screening in reading but screen students in math. If you can’t or don’t feel a need to screen all students in both reading and math, which student groups, grade levels, or subject areas are the most at-risk? These could be prioritized areas for a limited additional screening.

Creating a “treatment plan” for the months ahead

To return to our medical analogies, we must remember that Star tests are like check-ups with your physician. They provide useful information to help gauge whether the “patient” is responding to the treatment, but they are not treatment plans unto themselves. Here are some ideas for what to do this fall (and beyond) to address unfinished learning:

- Consider all available options to catch students up. Options include high-dosage tutoring, which can be provided either in or outside of the classroom, and extended learning time, such as before- and after-school programs and summer programs. Excellent summaries of research on different approaches are available in an article titled “The Science of Catching Up” in The Hechinger Report, and in a recent report from the Education Commission of the States.

- Follow the dialogue on accelerated learning. A significant pedagogical shift is occurring in how we address students who are performing below grade-level expectations. Traditionally, we spoke about “remediation” or “meeting students where they are.” The newest thinking is that we should instead “accelerate learning.” This is an umbrella term, with several strategies related to it. But the emphasis is on maximizing the time students spend with grade-level content, which has significant implications for how we plan daily instruction and intervention experiences. A succinct overview is provided in a recent EdWeek article. EdWeek’s “Deciding What to Teach? Here’s How” infographic shows you how to embed accelerated learning approaches into daily instruction.

- Decide which standards and skills to prioritize. When working to accelerate learning, serious consideration must be given to the most essential ideas of the grade-level and to the most critical prerequisite skills from previous grades. Renaissance’s Focus Skills Resource Center provides insights in both areas. Lists of the most critical skills for progress in reading and math, tailored to the standards of each state, are available, along with helpful overview videos for getting started.

- Consider which supplementary practice programs might be of assistance. Digital practice programs can keep students engaged in and out of the classroom, and they can provide additional insights into students’ ongoing progress. They can also support extended learning initiatives, both during the school year and over the summer. At Renaissance, we offer multiple practice programs that students can use in tandem with Star Assessments, including our myON digital reading platform; Freckle for math and ELA; Accelerated Reader, for independent reading practice; and Lalilo, for foundational literacy skill development.

Adjusting to our “new normal”

In March 2020, who had any idea that the disruptions would continue for so long? Back then, we naively assumed that in-person learning would resume in the fall, only to experience a 2020–2021 school year that was—in most locations—profoundly disrupted. We now find ourselves several months into the 2021–2022 school year still holding our breath that “normalcy” will return.

Heads down, grinding away at our work, we may not realize how long we have been toiling under the disruptions. A recent social media meme brought this clearly into focus for me by noting that today’s high school seniors have not experienced a “normal” year of schooling since they were freshmen. Similarly, our current elementary students up to grade 2 have never experienced a non-disrupted school year.

Let us hold out hope that the current year can qualify as a relatively normal one, and that the steps we take and the work we do to support student learning will contribute to this much-needed return to normalcy.

Looking for more insights on accelerating learning? Check out Dr. Kerns’s recent blog on making the best use of Star’s instructional resources this year. And to learn more about Star CBM, myON, Freckle, or other Renaissance programs, just click the button below.