January 21, 2022

Reading is an activity that takes many forms. It’s someone lounging in a window seat, lost in a good book. It’s also someone poring over an academic paper, looking for deeper understanding. It’s even someone skimming the latest news headlines while having a bite to eat. It’s an activity that can be mindful or nearly mindless. It can be 100 percent pleasure or 100 percent work.

Given reading’s many forms, is it any wonder that students need a variety of educational experiences to become skilled readers? While much of the work of schools is intently focused on standards-based reading instruction with grade-level texts, often paired with writing activities to demonstrate students’ depth of knowledge, isn’t there more to reading than this? When adults describe themselves as “avid readers,” is this what they have in mind? Do they really feel they’ve missed out if there isn’t a required writing activity at the end of every book?

I strongly contend that discussions about reading should recognize three distinct categories: (1) reading to students; (2) reading with students (instructional reading); and (3) Having students read independently. Each type of reading makes an important contribution to students’ literacy development, and—perhaps more importantly—different rules govern what constitutes “success” in each. For these reasons, failure to distinguish between categories can have a negative impact on what we do in the classroom. Let’s explore this point.

Reading to students

Research shows that reading aloud to students is of significant benefit to them. In Becoming a Nation of Readers, Anderson et al. (1985) note that “the single most important activity for building the knowledge required for eventual success in reading is reading aloud to children.” This statement has been echoed and extended by later commentators, including those highlighted below.

Given the propensity of human beings to learn language by hearing it spoken, is there any question that we should read aloud to students regularly? Yet some do question why, once students can read independently, teachers still need to read to them. As Linda Gambrell pointed out, a key reason is that “the everyday language that students hear does not prepare them to enter into the world of books, because both narrative and informational books represent ‘book language’ that is very different from spoken language” (quoted in Layne 2015).

Why do authors use drastically different language in written work? They need to do so because “speech usually takes place in a communicative context, meaning that some cues that are present in speech (e.g., gesture, tone of voice, facial expression) are absent in writing. To compensate, written language draws on a much larger vocabulary and more complex grammar: Noun phrases and clauses are longer and more embedded, and the passive, more formal voice is much more common” (Castles et al., 2018).

So, teachers will either (a) take the time to expose students to the advanced language of texts by reading aloud to them, or (b) fail to take this step and hope that students will somehow be successful when they encounter this unfamiliar world of advanced language on their own—clearly an unlikely occurrence.

When reading to students, text complexity is obviously a consideration. For students to optimally benefit, we should not read texts to them that they could reasonably access on their own. Layne (2015) positions reading aloud as helping students to “listen up.” This is because “the listening level of a child (the level at which he hears and comprehends text) is significantly higher than his silent reading level” until the two converge around grade 8. This makes reading aloud “the medium for exposing students to more mature vocabulary, more complex literary devices, and more sophisticated sentence structures than they would be finding in the grade-level texts they could navigate on their own.”

Layne’s general guidance is that teachers “consider selecting the majority of read-alouds from texts written one to two grade levels above the grade level [they] are teaching.” I’ve encountered other recommendations that suggest going a bit higher, two grade levels or more. In either case, it’s clear that reading to students has unique dynamics, as do the other two categories of reading.

Reading with students

I choose to refer to instructional reading as “reading with students” because instructional reading is not typically an activity that students undertake on their own. Instead, teachers call attention to specific words and details, pose questions, provide background information, facilitate conversations, and conduct “think-alouds” to scaffold the experience and to model close, thoughtful reading. In contrast to the uninterrupted flow that occurs when reading to students, reading with students is often punctuated by all sorts of activities. In other words, instructional reading is a mediated experience.

This type of reading rightfully consumes the majority of class time. It’s during this activity that reading “grade-level texts” is paramount. Also, the focus isn’t solely on what we read with students; there are also considerations around what we ask students to do in response. During instructional reading, whole-class or small-group discussions and written responses to open-ended questions are not only useful but mandatory for fostering close reading and deeper thinking about the text.

Guidance from the Common Core State Standards (CCSS), for example, expressly notes that “students need opportunities to stretch their reading abilities”—opportunities that instructional reading provides. But many educators miss the fact that these standards also note that students should “experience the satisfaction and pleasure of easy, fluent reading.” In other words, the CCSS expressly recommends both types of reading experiences—instructional and independent (pleasure) reading.

This brings us to the third and final category.

Reading independently

Although independent reading is overlooked in many schools, there are many references to and calls for extensive independent reading within different standards sets. As noted above, the CCSS calls for students to “experience the satisfaction and pleasure of easy, fluent reading.” Similarly, the Texas Essential Knowledge and Skills (TEKS) state that “the student is expected to self-select text and read independently for a sustained period of time” across all grade levels. The connection between wide reading and higher levels of literacy performance is well documented, and one analysis found that students who read independently for anything less than 15 minutes per day simply cannot keep up with rising expectations.

Wide independent reading holds significant and undervalued potential. This essential activity fosters the self-teaching necessary to become highly literate (Share, 1995; Share, 1999). Early on, it helps elementary students learn the letter combinations of English and immediately recognize more words by sight. In the middle and upper grades, it transitions into an activity that helps readers develop vocabulary, background knowledge, and other critical elements of literacy.

Not only are there clear academic benefits of independent reading, but motivational benefits as well. Daniel Willingham (2015) points out that “one source—probably the primary source—of positive reading attitudes is positive reading experiences.” But when “reading” is always a challenging and arduous activity—think of close instructional reading of complex texts, followed by a writing assignment—students are unlikely to see it as pleasurable. For this reason, Willingham recommends that schools set aside at least 15 minutes a day for students’ pleasure reading. He remarks that this “is the best solution [he] can see for a student who has no interest in reading,” because “it offers the gentlest pressure that is still likely to work.”

For some students, daily independent reading time may actually be their first experience of taking pleasure in reading—but only if we understand and recognize the difference between this and the two other categories.

Different categories, different rules

I noted earlier that different rules govern what counts as “success” within each category of reading. Let’s explore this point through the lens of text complexity.

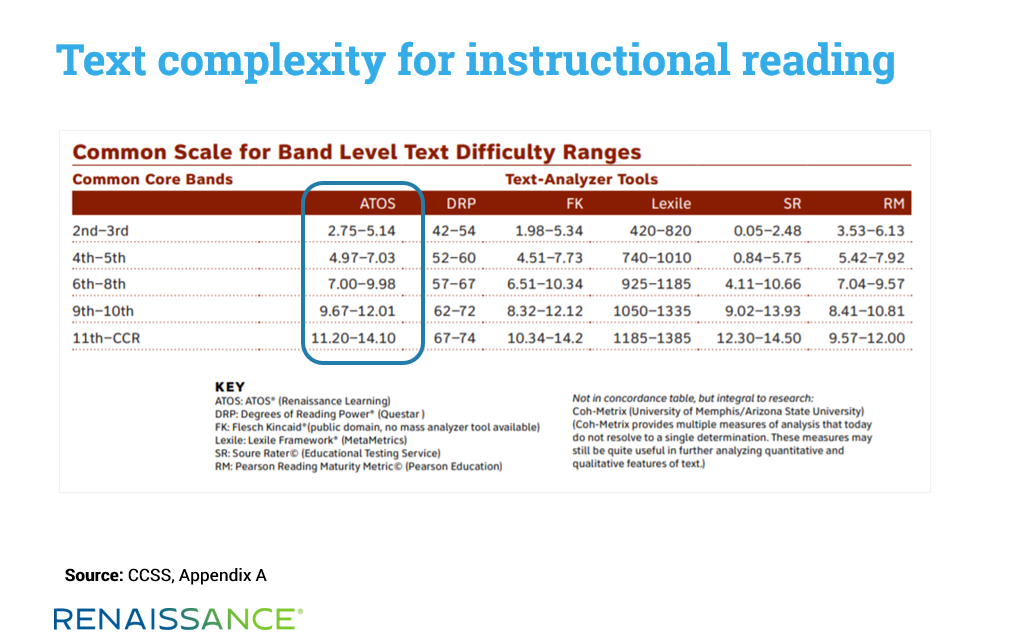

The CCSS, for example, has specific recommendations for instructional reading through the “text complexity grade bands,” as shown in the table below. While other standards sets might not quantify text complexity in this level of detail, there is always some consideration of or guidance about texts that represent “on grade level” for instructional reading.

Also, think about how student activities vary across the categories. With instructional reading, we want students to think deeply and analytically about the text, and to respond—most likely in writing—to open-ended, text-based questions. In contrast, when students are reading independently for pleasure, we can afford to be a bit less concerned about text complexity.

The “satisfaction and pleasure of easy, fluent reading” are not afforded when we use the text-complexity recommendations for instructional reading as guidance for what students are to read during their independent (pleasure) reading. For this reason, most structured programs around independent reading suggest reading ranges for texts that are lower than those used for instructional purposes.

As Willingham (2015) notes, “Academic reading feels like work because it is work. But pleasure ought to be the litmus test for reading for pleasure.” He adds that the opposite is also true: while some educators might “like to think that academic reading is pleasurable…‘pleasure’ is not a litmus test” for the activities we associate with instructional reading. This is to say that students should find independent reading pleasurable—which is unlikely to occur if we’re always requiring them to read at the edge of their abilities.

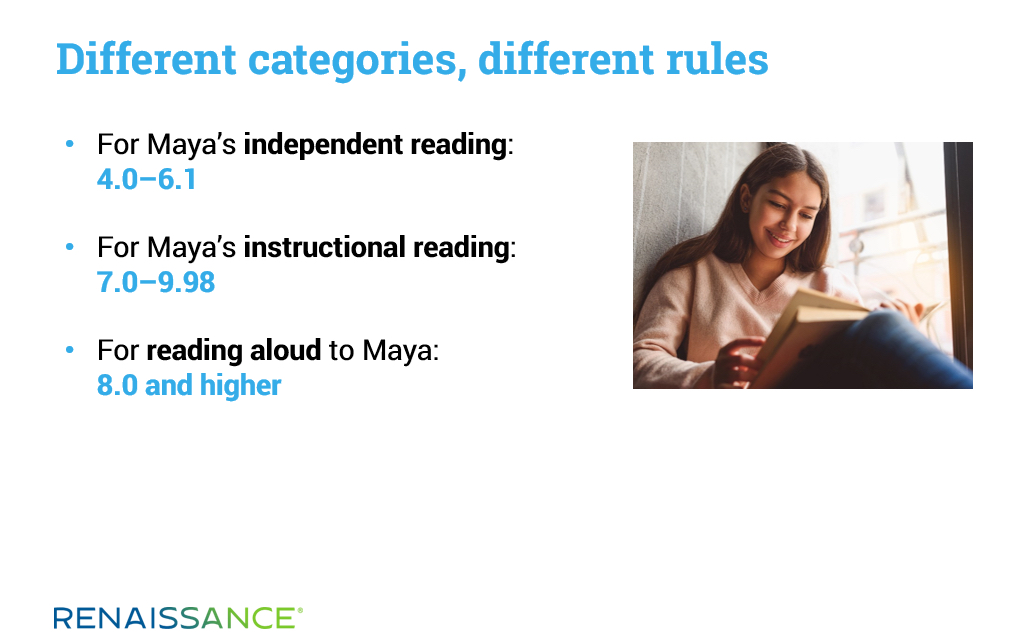

Let’s see how this discussion of text complexity might look for a hypothetical grade 6 student named Maya. Assume Maya takes the Star Reading assessment and receives a scaled score of 1068. This translates to a Grade Equivalent (GE) of 6.0, and a recommended reading range—or Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD)—of 4.0–6.1 for independent reading. If Maya lives in a CCSS state, the text complexity recommendation for instructional reading for grades 6–8 is text written at 7.0–9.98. Finally, if most students in Maya’s class are performing at a similar level, her teacher would be looking for texts written at 8.0 or higher for read-aloud.

In other words, three types of reading, three different sets of rules.

On misunderstanding the power of reading

On the surface, delineating the three types of reading seems simple and straightforward. Yet I find that they are often misunderstood. For example, one administrator recently pushed back on allowing students to use the myON digital platform for independent reading, because students might find and read books that are below their grade level. In his mind, all student reading must be “at grade level.” Clearly, this is pitting the text complexity concerns of instructional reading against the desire for the pleasure of “easy and fluent” independent reading. There is a time and a need for both.

This lack of understanding is also demonstrated by people I’ve encountered over the years who suggest that the comprehension questions in Accelerated Reader are not “deep” enough, and that students must be given open-ended discussion questions and writing prompts for every text they encounter. Again, this is to bring the pedagogical considerations of instructional reading into the world of independent, pleasure reading. If we overload pleasure reading with requirements and assignments, we’ll quickly sap the pleasure—and students’ motivation—from the activity.

Whether you draw on the Book of Ecclesiastes or the classic song by The Byrds, it’s clear that “To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven.” In this spirit, I’ll once again contend that in every classroom and at every level, students must be read to, they must be read with, and they must read independently. It’s only by acknowledging the critical role of each type of reading—and by respecting the differences among them—that we have any hope of creating “a nation of readers.”

References

Anderson, R., Hiebert, E., Scott, J., & Wilkinson, I. (1985). Becoming a nation of readers: The report of the Commission on Reading. Washington, DC: National Academy of Education.

Castles, A., Rastle, K., & Nation, K. (2018). Ending the reading wars: Reading acquisition from novice to expert. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 19(1), 5–51.

Layne, S. (2015). In defense of read-aloud: Sustaining best practice. Portland, ME: Stenhouse.

Lemov, D., Driggs, C., & Woolway, E. (2016). Reading reconsidered: A practical guide to rigorous literacy instruction. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Routman, R. (1991). Invitations: Changing as teachers and learners K–12. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Share, D. (1995). Phonological recoding and self-teaching: Sine qua non of reading acquisition. Cognition, 55(2), 151–218.

Share, D. (1999). Phonological recoding and orthographic learning: A direct test of the self-teaching hypothesis. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 72(2), 95–129.

Willingham, D. (2015). Raising kids who read: What parents and teachers can do. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Looking for engaging titles to support your students’ reading practice? Explore What Kids Are Reading, the world’s largest annual survey of K–12 student reading habits. And to see everything that the myON digital reading platform has to offer, click the button below.