July 3, 2023

The recent release of the 2023 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) data brought another flurry of reporting on the impacts wrought by pandemic-related disruptions to schooling.

In fact, a recent District Administration article quoted Dr. Peggy Carr, commissioner of the National Center for Education Statistics, which oversees NAEP, remarking that “the ‘green shoots’ of academic recovery that we had hoped to see have not materialized, as we continue to see worrisome signs about student achievement and well-being more than two years after most students returned for in-person learning.”

To be sure, there are some new and alarming findings in the NAEP data, such as dropping attendance rates, decreases in the time students spend reading, and decreased enrollment in algebra. There are also some findings that have been consistently documented since the pandemic began: scores are down at all grade levels, math has been more affected than reading, and some student groups have been disproportionately affected.

After all this time, however, it’s becoming almost impossible to distinguish one report on unfinished learning from another. While addressing the needs students currently have requires that we keep our sense of urgency high, what many of us are also longing for are fresh insights and a narrowing of our focus.

Acknowledging that we can’t solve everything at once, where do we focus our attention for the greatest impact? In this blog, I’ll offer several suggestions based on an analysis of both NAEP and other recent assessment data.

Using NAEP data to put “learning loss” in perspective

It’s a good day when I read something that provides me with an insight, but it’s a great one when I read something that provides me with an epiphany. Those don’t come along often, but when they do, they cause us to completely reorganize the way we interpret the world. We just can’t look at things the same way again. Such was the case when I read a 2020 Education Week article on learning loss written by formative assessment expert Dylan Wiliam.

While “learning loss”—or “unfinished learning,” or whatever term you prefer for whatever the academic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic were—remains a hot topic, Wiliam cautions that “it is also important to put whatever learning loss there has been in perspective” (my emphasis). And the perspective he suggests is not solely focused on the direct impacts of the pandemic but considers learning loss in relation to the achievement gaps that already existed. When we do that, we find that we may have been focusing too closely on the wrong things. In other words, we have an epiphany.

Writing in the back-to-school season of 2020–2021, Wiliam began with 2019 NAEP data for math and then “extrapolate[ed] beyond the grades tested by NAEP using nationally normed standardized tests” to suggest the range of performance in “a nationally representative 4th grade class of 25 students.” His analysis suggested that, in such a classroom, “there were five students whose math achievement was no higher than the average 1st grader, and two students whose achievement would match that of the average 9th grader.” In other words, “in a nationally representative class of 4th graders, there [was] at least an eight-year spread of achievement” prior to the pandemic.

Wiliam added that “even if we assume that students learned nothing after schools began closing down in March [of 2020], it means that rather than an eight-year spread of achievement, a returning 5th grade class [in the fall of 2020] would have [had] an eight-and-a-half year range of achievement” after the pandemic hit. The headlines focused solely on this half-year increase rather than the existing 8-year spread.

That seemed a bit off to Wiliam. It seemed to lack perspective.

Comparing pandemic “learning loss” to existing achievement gaps

Wiliam was not alone in making such a claim. Several months earlier, Will Lorié with the National Center for Assessment asserted that previously existing performance gaps “are greater than any differential ‘learning losses’ we will find between relatively advantaged and disadvantaged groups due to spring 2020 school disruptions.”

Heather Hill and Susanna Loeb made a similar point in a May 2020 Education Week article, stating that “even if the loss is on the larger side—say, the equivalent of three months—this change is small compared with typical existing learning differences among students as they enter a new grade.”

Now, a time stamp is critically important when we consider these authors’ statements. They were writing in the first several months of the pandemic—between May and August of 2020.

Think back to that time period. At that point, we were still a bit naïve about how things were going to unfold. We were just beginning the 2020–2021 school year with hopes that it might be rather normal, but our hopes were soon dashed. Continued COVID-19 outbreaks and variants created a dynamic where the school year, at best, involved shifting instructional delivery models for many students, and a full year of remote learning for others.

Disruptions to schooling occurred widely across that school year and well into the next one (2021–2022) as well. Given that disruptions went on for far longer than these authors might have accounted for, does their assertion that pandemic-related learning impacts would be relatively small when compared to previously existing achievement gaps still hold true?

It’s time that we revisit this.

Considering NAEP data alongside Renaissance Star Assessments data

Since the fall of 2020, Renaissance has been publishing our How Kids Are Performing report series. Soon, we will transition from static reports to an interactive website that presents overall metrics on both performance and growth in reading and math that are updated seasonally and draw from our widely used Star Assessments.

Though it began as a way to study pandemic-related impacts—particularly before summative systems such as NAEP went back online—How Kids Are Performing will now continue as a high-level barometer of student performance and growth.

While Star Assessments data from the 2022–2023 school year is still being analyzed, we can already shed some light on whether the ideas advanced by authors in 2020 about the relationship between pandemic-related impacts and existing achievement gaps still hold true.

Let’s use grade 4 math as an example, to match Wiliam’s analysis. Using 2019 NAEP data, he estimated that a previously existing achievement gap of roughly 8 years might have been widened by an additional half a year. How does this compare to our How Kids Are Performing data?

In the fall of 2019, the mean scale score (SS) on Star Math for over one million grade 4 students nationally was 973, with a standard deviation (SD) of 60. By the fall of 2022, the mean SS was 964, with an SD of 67. These shifts indicate both lower performance and a wider range of scores.

We then used the mean and SD to determine the range of scale scores representing plus or minus 2 SD, which would then reflect the performance of 95% of the population. When those SS are converted to Grade-level Equivalent (GE) scores, that results in a GE range of 2.0–7.7 (a 5.7-year range) for 2019–2020, and of 1.6–8.0 (a 6.4-year range) in 2022–2023.

In other words, between 2019–2020 and 2022–2023, the range of performance in a typical grade 4 classroom widened by 0.7 GE, or 7 months. So, things seem to closely mirror what Wiliam projected, with a bit larger increase in the range than he anticipated.

Understanding achievement gaps in reading and math

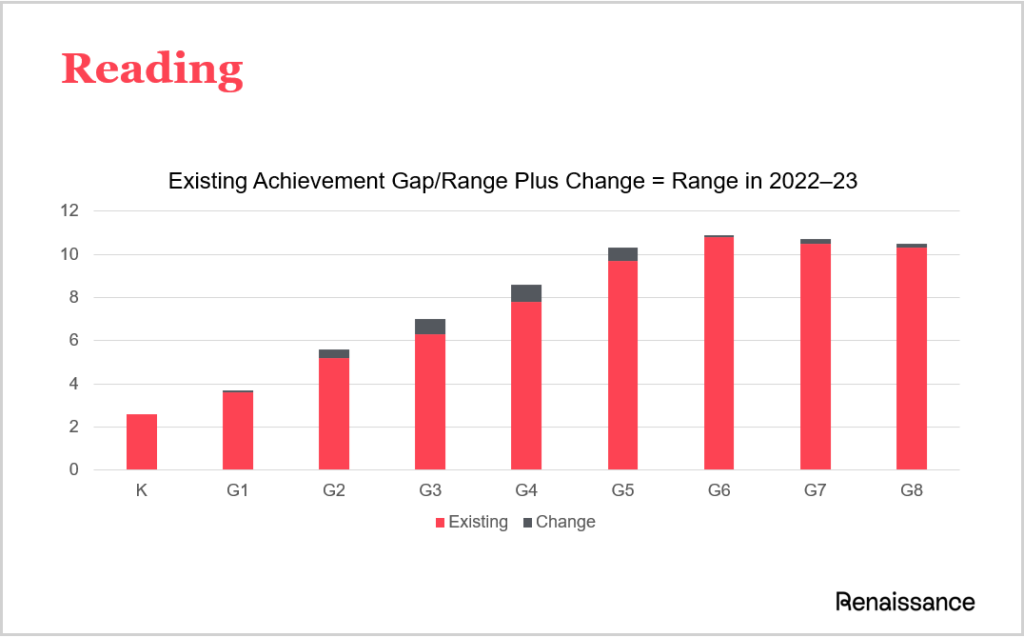

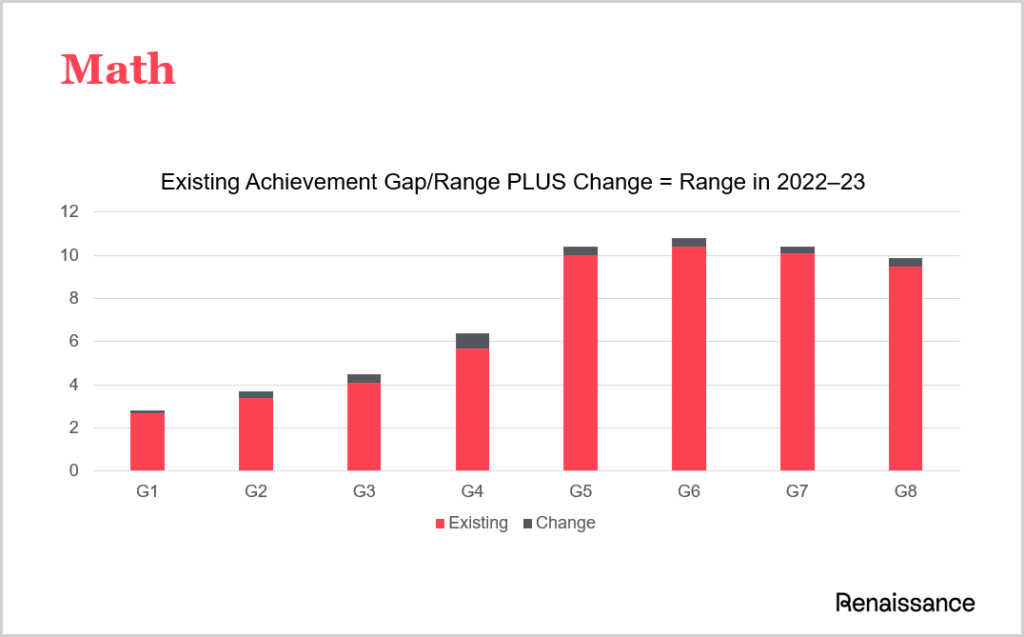

While we’ve used grade 4 math as our example here, these same dynamics played out across all grade levels and both subject areas. (The only exception is that kindergarten students in 2022–2023 started out at exactly the same level of performance in reading as students in 2019–2020.) The summation of our analyses is presented in the following graphs, where red represents the achievement gap (range of performance) prior to the pandemic at each grade level, and black represents the pandemic-related increases:

As is often the case, we began exploring one thing—how much the gap had widened due to the pandemic—and found something we had not expected. It’s quite interesting to observe the differing ways the overall achievement gap widens between reading and math:

- For reading, the increase in the gap is fairly steady. In kindergarten, it begins with an achievement gap of about 2.6 years, and that gap steadily widens until it plateaus in the middle grades.

- For math, things begin similarly, with a gap of 2.7 years in kindergarten. However, things change radically between grades 3 and 5, when the gap mushrooms from 4.1 years to 10 years. In short, math realities shift quickly and dramatically for many students across a relatively short period of time—and this was already the case before the pandemic.

Additionally, while full details will be available when the new How Kids Are Performing website launches in late July, I would offer that we are seeing some of “the ‘green shoots’ of academic recovery” that are not reflected in the latest NAEP data. Here, I’m defining a “green shoot” as something that is no longer in decline and, though not back, is at least headed toward pre-pandemic levels.

Examining math and reading performance from kindergarten through grade 8, we see four instances of continued decline. At many grade levels, student performance in 2022–2023 is directly comparable to performance in 2021–2022, suggesting no further decline. In eight instances, we are actually seeing a rebound in scores—not back to pre-pandemic performance levels, but still rising.

How to address achievement gaps in the year ahead

So, what are the takeaways as educators prepare for the new school year? First of all, I hope we now have the insight that the pandemic-related disruptions to learning are substantial, but also that they are dwarfed when compared with pre-existing performance gaps. Then, we also need to acknowledge that math performance gaps increase substantially in grades 3–5—an area that deserves especially close attention in the year ahead.

Of course, conversations about achievement gaps are not new. As Lorié observed, “Since the 1960s, schools have been called to close inter-group gaps.” This is a helpful reminder that if we merely take traditional approaches, we likely won’t have much hope to substantively achieve recovery. That approach harkens to the familiar definition of insanity—doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.

But several significant changes in our practice are occurring that hold significant promise in the new school year:

#1: Science of Reading

Chief among these changes is the widespread embrace of the Science of Reading. Over a relatively short period of time, massive changes have occurred in relation to reading curricula and instruction. The state of Mississippi, for example, has experienced significant increases in reading performance. Given that Mississippi led the way with the Science of Reading, we have reason to hope that other states will experience such increases as they also embrace reading science.

While many providers offer curricular materials and professional development aligned to the Science of Reading, few can match the assessment capabilities offered by Star Phonics. This powerful skills screener focuses intensely on early grade phonics skills and provides student-by-student and skill-by-skill feedback so that teachers can ensure the critically necessary foundation of phonics is unquestionably put in place.

Lalilo, another relatively new tool in the Renaissance family, also supports the Science of Reading by providing both adaptive and targeted practice opportunities for students across the skills areas specifically called out by the National Reading Panel: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. For students, this takes the form of an adventure game with worlds to explore and tokens to earn, but as students “play” Lalilo, their teachers receive valuable feedback on the skills they are working to master.

#2: Accelerated Learning

Second, our pedagogical approach when students are behind is shifting from one of remediation to one of Accelerated Learning. Initial research on this shift has found that “students who experienced learning acceleration struggled less and learned more than students who started at the same level but experienced remediation instead.”

Given the two essential questions one must answer to operationalize Accelerated Learning—“Which grade-level skills are most essential?” and “What are the necessary prerequisites to those skills?”—there is hardly a better source to support the approach than Renaissance’s Focus Skill Resource Center. This free website allows users to see the most essential skills for progress in reading and math tailored to the standards of each state, helping to prioritize instruction.

Educators using our Star Assessments will also find Focus Skills flagged on instructional planning reports. Those who are using our Freckle program have the added ability to assign ELA and math practice that aligns with essential Focus Skills.

#3: More effective MTSS

Of course, all of this work should be undertaken through a multi-tiered system of support (MTSS) framework, which has been taking root in school processes for the last 15 years or more. While FastBridge and Star Assessments are widely used in this space and are highly rated for both screening and progress monitoring, more districts are now expanding their analytics capabilities by adding eduCLIMBER.

eduCLIMBER is an MTSS collaboration and management platform that provides data integration, warehousing, and visualization capabilities. Designed by a school psychologist, it includes practical features designed to tame the paperwork, forms, and reporting required within the MTSS process.

Also, as part of the MTSS, considerations of social-emotional behavior elements are on the rise. We are excited to announce that new social-emotional assessment capabilities will be added to our Star 360 suite this fall. Star 360 subscribers should look for additional information as we approach the back-to-school season.

Connected solutions to move learning forward

The reframing of unfinished learning to not only focus on the short-term changes but to also consider the larger perspective of performance gaps is not intended to belittle the problem. Clearly, the pandemic-related disruptions made a bad situation worse. As Wiliam notes, “This does, of course, present teachers with huge challenges, but these are challenges that teachers have been dealing with for years.”

Fortunately, as we work to move forward and once again take on the challenge of raising performance and narrowing gaps, we do so with both new clarity and new tools.

If you’d like to learn more about Star Phonics, Lalilo, eduCLIMBER, or other solutions from Renaissance to support learning recovery, please reach out.