November 3, 2023

You’ve probably heard the old adage: If some is good, then more must be better. The irony is that this statement rarely holds true. Even with things that are good, we eventually reach the point where we have enough of them. More doesn’t really add anything.

Such is the case with the number of items on a universal screener or other interim assessment. Many of the leading providers hold to the flawed “more must be better!” belief, and they create assessments that are unnecessarily long. As a result, time that should be spent on instruction is instead spent on testing—without educators gaining additional insights to help guide their decision making.

Let’s explore this important point.

Efficient assessment and the perfect screening tool

By any estimation, the vast majority of US districts are served by three interim assessment providers: Renaissance, plus two other companies that offer far longer assessments. So long that—in some cases—the assessments have to be administered to students over multiple days.

In my new Assessment Masterclass video, I describe “the perfect screening tool.” Here, I refer to the guidance from professional literature that universal screening should be:

- Quick

- Low cost

- Repeatable

- Practical

Why is this point so important?

As conceptualized in a multi-tiered system of support (MTSS), screening is like a quick physical examination in a medical setting. It should involve a relatively short evaluation of key metrics associated with overall health. It should not involve a CAT scan, MRI, colonoscopy, or other specialized procedure.

In a world where there is tremendous concern about over-testing, purpose-built assessments with documented reliability, validity, and precision that are also of optimal length should be embraced as ideal—as many Renaissance customers do. However, our competitors in this space—in attempting to sell their longer, less efficient assessments—play up the “old adage” message, with the assumption that if having some assessment items is good, then having more items must be better.

Understanding an assessment’s value—and cost

To anyone who has followed Renaissance’s core educational beliefs for some time, it will not be a surprise that we so strongly focus on providing assessments that offer a high rate of return. In fact, our assessment design belief for decades can be expressed using this simple formula:

The formula states that the value of an assessment must be measured against the information it provides (“I”), in consideration of the cost (“C”) involved. Here, cost refers not only to the literal cost of purchasing the assessment but also to the cost of administering and scoring it.

Calculating the cost of an assessment

Let me give you an example of what I mean. Years ago, in the early days of MTSS and Response to Intervention (RTI) frameworks, I was speaking to an administrator about using Renaissance Star Assessments for universal screening. She responded that she wasn’t planning to purchase an assessment at all, because she’d recently found a free screener online. As she discussed this screener, however, it became clear that a significant amount of her teachers’ time would be required:

- Teachers first had to print individual test forms (aka skill probes) for each student.

- They then had to administer these probes to students one-on-one.

- Once the scores were manually recorded, the teacher was left with a spreadsheet full of individual data points, with no ability to aggregate or disaggregate the data for analysis.

Clearly, what this administrator failed to acknowledge is that once the first page of the first test form rolled off of the printer, the assessment was no longer “free”. The amount of time required for preparation, administration, scoring, and reporting increased its cost exponentially.

At one point, the cost of our computer-adaptive Star Early Literacy assessment was compared to a free, paper-based assessment of early literacy skills that had to be administered and scored manually. When teachers’ time was factored in, Star Early Literacy was found to be the less expensive option—with a significantly lower impact on instructional time.

Supporting effective screening

Discover Renaissance’s universal screening tools for reading, math, and social-emotional behavior.

Determining the value of an assessment

So, to determine the value of an assessment, all costs must be considered, including teachers’ and students’ time. As the formula states, the amount of information being provided must be considered as well. At Renaissance, our goal is to build assessment tools that provide educators with maximum value (the amount of information provided to them) in relation to the cost (the amount of time) they put in.

Here, I’ll admit to a somewhat “covert” action. Not long ago, I was speaking with a group of teachers who used an assessment from one of our competitors. I took the opportunity to ask them about the assessment, what they valued in it, and how they were actually using it in their schools.

What I found was a massive disconnect between what the company suggested as the appropriate use of the assessment, and what teachers actually did with it.

The company positions the tool as ideal for fall, winter, and spring screening within MTSS, to help teachers understand which students are meeting benchmark and which would benefit from additional supports. However, the teachers reported that they only used the assessment once or twice each year. This perplexed me, so I asked why they didn’t administer it more often.

There was a consistent response: “It just takes so much time.”

Said differently—and through the lens of the formula I introduced earlier—this sentiment can be summed up as: “When I consider the amount of time the assessment takes in relation to the information it provides, I don’t see the value in administering it more often.”

Prioritizing efficiency—and assessment reliability

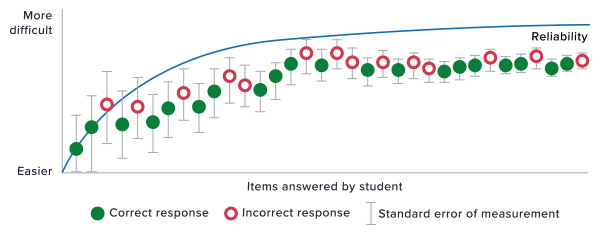

Beyond this consideration of value, educators should also consider that, when it comes to the length of an assessment, there is a point of quickly diminishing returns. This is illustrated in the following graphic:

This graphic provides a visual depiction of the operation of a computer-adaptive test. Moving from left to right, we see that the test taker is presented with items, indicated by the circles, to which he or she responds either correctly (green) or incorrectly (red). The test then adapts by presenting a more difficult (higher vertically) or a less difficult (lower vertically) item.

As more items are presented, the standard error of measurement, reflected by the gray bars, decreases. This means that the reliability of the final score, as indicated by the blue line, increases.

The arc of this blue line reflecting reliability is a critical consideration, because it’s where we most clearly see the point of diminishing returns. Notice that as the test begins, reliability increases drastically as the first few items are administered. But, over time, the blue line begins to level off. It never goes completely flat and, in a general sense, it is true that additional items can positively impact reliability—at least until the test taker begins to experience fatigue.

But notice the pattern of diminishing returns. Five or ten additional items would result in only a slightly higher degree of reliability, while substantially increasing the length of the test. Is this very modest increase really worth the lost instructional time that would be involved?

Assessment reliability and assessment value

Many assessment providers fail to understand this important dynamic. Assessments are about value and information. When they take too long—in other words, cost too much—they fail to have value to educators. Ironically, some of our competitors do seem to realize this. As a result, they’ve built “attentiveness indicators” into their assessment tools, to alert teachers when students’ focus may be flagging, and they simply start to guess.

I suppose such a feature is needed when your test can take 45–60 minutes (or more).

During my days as an Instructional Specialist, I once watched a dedicated, high-achieving student take an assessment provided by one of Renaissance’s competitors. After 30 minutes, I was beginning to question the process. After 45 minutes, I was starting to feel uncomfortable. After nearly 70 minutes, when the student finally finished the test, I realized there was no amount of information it could provide that would have made that amount of arduous testing time justified.

Factors that impact assessment reliability

To return to an earlier point, let’s be clear about the factors that most directly impact reliability. Like our competitors, Renaissance favors computer-adaptive tests that respond to test-takers and greatly improve efficiency by adjusting items based on students’ responses. But we must acknowledge that—by design—these tools continue to adjust content upwards until students reach the “edge” of their performance.

This creates a dynamic where taking such a test can be quite draining. So draining that one of our competitors—given the length of their assessment—suggests that you might want to break the test administration into multiple sittings, to give students time to recover. I certainly find myself wondering how this lost instructional time can be justified, given that reliable scores can be achieved using more practical assessments.

I also fully acknowledge, as our competitors so strongly do, that the length of an assessment is a factor in its reliability. As the graphic illustrates, an assessment must have a certain minimum number of items to produce a reliable score. So, how is Renaissance able to produce highly reliable scores—as validated by the independent National Center on Intensive Intervention—with 10–20 fewer items than our competitors’ tests?

We’re able to offer a shorter test with on par reliability because we focus so intently on the quality of our items. Our multi-step item development and review process is among the most stringent in the industry. This is because only the best items will result in assessments that reflect our belief that an assessment’s value depends on the information provided, divided by the cost involved. Items that other providers might include in their assessments simply do not meet our psychometric requirements.

In short, our goal is an assessment that isn’t too long (diminishing returns, lower perceived value, fatigued test-takers) and isn’t too short (reliability), but one that is just right. One that offers value to educators when they consider all of the costs involved, and all of the pressure they face to make the best possible use of their limited time for instruction.

Spend your instructional minutes on instruction—not testing

Seasonal screening in reading, math, and social-emotional behavior is an essential component of an effective MTSS framework. Yet too often, schools and districts select assessment tools that are not optimally designed for this purpose. The result is lost instructional time or—worse—teachers “opting out” of the screening process altogether.

If you’re looking for reliable, efficient, and research-based assessments designed for universal screening, Renaissance can help. Both Star Assessments and FastBridge meet the four essential criteria of the perfect screening tool:

- Quick

- Low cost

- Repeatable

- Practical

As a result, they provide you with key insights on students’ performance and growth—as well as actionable next steps for instruction—without consuming significant amounts of instructional time.

Learn more

To learn more about Star Assessments or FastBridge, or to arrange a personalized demonstration for your team, please reach out.