January 8, 2021

Like nearly all children in the 1970s and 80s, I fully embraced the early video games of that era. For many, the only access to these was at video arcades. But if you were really fortunate, you had one of the early home computers—think Commodore 64, Atari, Tandy, or the Apple IIe.

My brother-in-law was a techy person, and we were Atari people. My favorite game for our Atari 800 was called Star Raiders. You piloted your space fighter from quadrant to quadrant encountering the enemy and returning to base when needed for refueling or repairs. The moment the game started, you did two things: you pressed CTRL-S for shields and CTRL-C for computer.

As the names imply, the shields provided protection while the computer provided navigational information. If it became damaged in battle, navigating was a far less reliable and a far more manual process. If you ran low on fuel and could not make it back to base quickly enough because of your diminished navigational capacity, it was game over.

So, what does this have to do with the 2020–2021 school year? In an earlier blog, I suggested that we’re currently living in a footnote of history, given the disruptions caused by COVID-19. This means that in the future, when people look back at student data from this time, there will always be a footnote or an asterisk to remind them that the information must be considered through the lens of the pandemic’s disruptions. As we drift through this footnote, I’m now asking whether we have our computers “turned on” to get the navigational information we need.

Confronting the data void

In a profession where the release of high-stakes summative data has been a regular occurrence for nearly two decades, we’re just finding out what it’s like to perform our roles without the flow of information from state tests. There will never be any summative data for the 2019–2020 school year. While I’m not usually a betting man, I’d say that the odds are split on whether we’ll have state summative testing this spring. If state testing does occur, the results won’t be back until the school year is over.

If data from these summative tests were the only source of guidance—our only navigational computer— then schools would be totally adrift this year. But they’re not. We have interim assessments that can easily produce normed scores on relative performance, such as percentile ranks (PRs), and on growth, such as Student Growth Percentiles (SGPs). Interim assessments are critical because they provide information that other tools cannot.

Some commentators, who are not fully acknowledging the critical role of interim assessments this year, have focused primarily on formative assessment instead. They are correct to advance this type of assessment as a critical element, because the relationship between student growth and quality formative assessment strategies is well-documented. However, in the same way that a variety of tools allows a master craftsman to produce quality results, a variety of assessment tools is necessary for teachers to achieve optimal student growth.

Answering essential questions

Formative tools do an excellent job of providing feedback at the instructional level on individual skills or a small set of skills. They can definitively tell you whether a student has mastered a given skill, while normative data provides different yet equally important insights. For example, formative tools can tell you that across six weeks of instruction, a student mastered 23 skills. However, the normed growth metric of an interim tool can tell you whether, while doing so, the student was progressing at a rate equal to, above, or below her grade-level peers. In other words, was the student maintaining her current overall level of performance, moving ahead, or falling behind during this time period?

And it’s not just about growth metrics. There are many questions currently being posed by stakeholders—parents, community members, teachers, school boards—that relate to overall school and district performance and require normative information to answer (e.g., What has been the true impact of the “COVID-19 Slide”? How are our students really performing this year?) Normed scores uniquely allow us to understand each student’s performance and growth relative to that of others.

A definitive case can be made for the use of interim assessments to answer essential questions about performance. The question is whether, amidst all of the disruptions and pressures they’re facing, school leaders are making the use of interim assessments a priority. I’m pleased to report that many are.

Supporting learning for all students

Year-over-year usage data for Renaissance Star Assessments reveals that the vast majority of educators are continuing to use Star as much as they did before COVID-19. For most students, this means a regular cadence of fall, winter, and spring screening to confirm adequate performance and growth. There is, however, a small portion of schools that have consciously chosen not to give any interim assessments this school year. There’s another group that may not have made a conscious decision, but have simply neglected to use their interim tools. All of these schools have their navigational computers turned off. They are currently adrift in the void.

I’m amazed at how long some educators are willing to drift without normative information—and curious about their rationale for this. Some view interim assessments’ normative scores as simply a local extension of summative assessments. They’ve asserted that there’s no need to administer interim tests because “there’s nothing to predict”—as if the onl role of an interim test is to predict summative outcomes. But the best interim assessments, when used well, do so much more. They support our RTI/MTSS implementations, help us screen students for characteristics of dyslexia, support equitable goal-setting, and provide critical information to quantify the impact of the COVID-19 Slide.

I remember when I first encountered Star Assessments more than two decades ago, years before No Child Left Behind went online and anyone really knew what “high stakes accountability” was all about. Summative tests existed, but they were administered far less often. Their results were excessively delayed and barely available to me as a teacher. Reporting was provided on paper, and even the basic analytical tools and disaggregation capabilities of today were non-existent. Most teachers now have immediate access to a wealth of data on their students, while not so long ago accessing any normative information on a student was an arduous task that involved getting access to the records room and manually going through paper reports in a student’s permanent file. Then came Star.

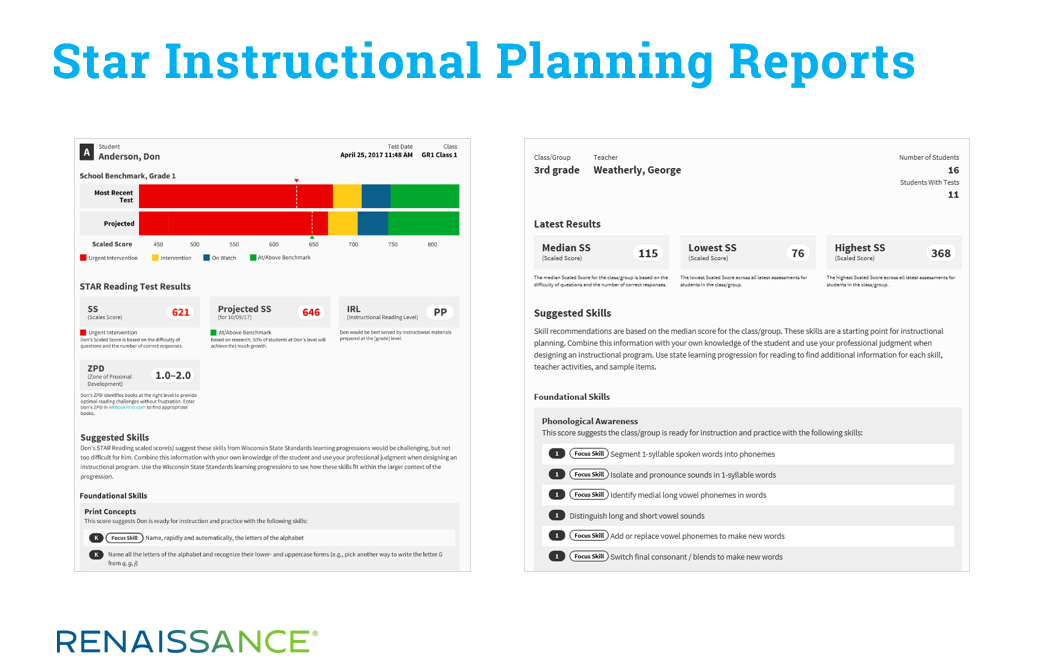

As a teacher, getting access to Star was the first time that I ever had any control over a normed assessment, and that was powerful. I could administer the test when I wanted to confirm or alleviate concerns I had about student performance. Star provided information on newly enrolled students on whom we had little other information, and it provided powerful reports for parent conferences. Star produced information I could use immediately, and it marked the beginning—for me and for many other teachers of that time period—of a new era of using assessment information for instructional planning.

But, as I write this, there are districts that are coasting along without having administered any interim assessments since last winter, and that have no plans to give any such tests for the remainder of the school year. This is an extremely long time to go without navigational data. It’s like flying a plane for hours without confirming your altitude or direction—simply drifting along without confirming that you’re truly getting closer to your destination.

Now for the good news: the computer can be switched back on at any time. Many scores (e.g., percentile ranks) are immediately generated and, while schools that have not tested yet will always have a gap in their data, a new test brings much new information. The longer that schools go without testing, however, the more prolonged the gaps in their longitudinal data become.

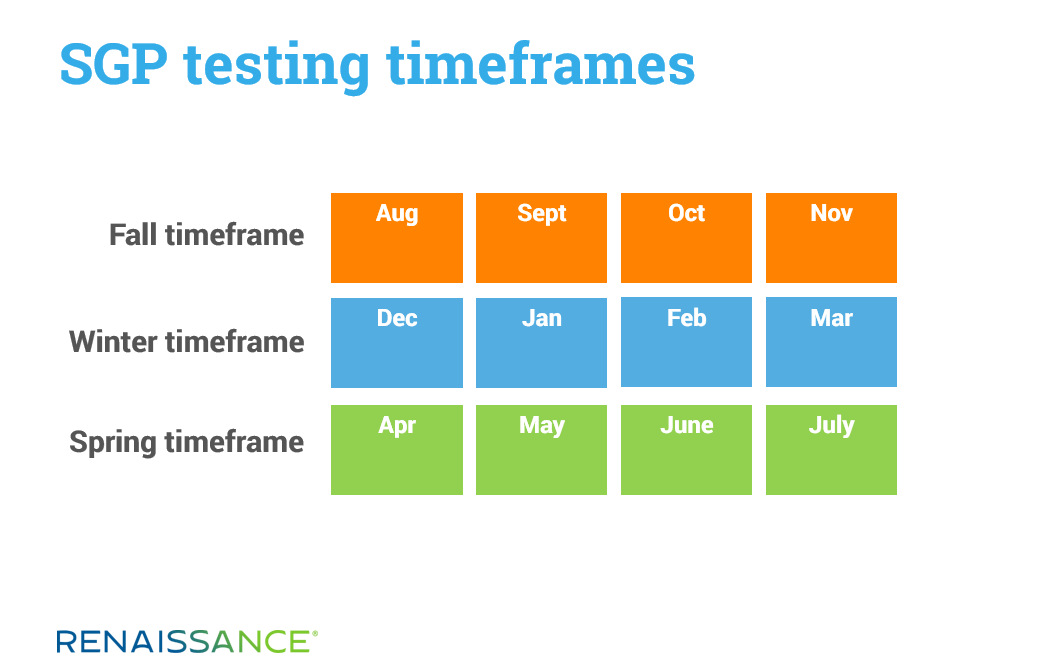

Also, because more specialized scores, like Student Growth Percentiles (SGPs), require testing within specific windows of time, going back online with them is a bit more complex. Calculating SGPs requires a student testing history. Many schools that had regularly been using Star for fall, winter, and spring screening did not administer the assessment last spring, due to COVID-19 building closures. Once they administered a Star test this fall, however, SGPs (Fall 2019 to Fall 2020) were generated, because the calculations can still be accomplished even with one testing window missing.

Schools that skipped testing last spring and consciously chose not to—or merely neglected to—administer Star this fall have temporarily lost access to SGPs, because the score’s calculation cannot be accomplished with two skipped testing windows (Spring 2020 and Fall 2020). They are adrift without an important growth metric for the first half of this school year. They do, however, still have the opportunity to “turn their navigational computers back on” for the second part of the year.

While the fall window for SGP scores, having run from August 1 through November 30, is now closed, the winter window is currently open. Any Star test taken from December 1 through March 31 is a step taken toward bringing the SGP “navigational system” back online for the second half of the year. With a test in both the winter window and the spring window (December 1 through July 31), a Winter 2021 to Spring 2021 SGP will be calculated, providing a key metric on students’ growth during the remainder of the school year.

To schools that have opted to cancel interim testing this year, I say: it’s time to bring your navigational systems back online.

Learn more

Renaissance offers a suite of universal screening tools to help you better understand students’ performance and growth. Connect with an expert to learn more.