August 27, 2021

As I sent my kids back to school last week, I felt a mix of emotions. I was excited that they were going back to in-person learning, with new teachers and new courses. I was nervous about the impact of the Delta variant, given that COVID-19 vaccines are not widely available for young children. However, I was hopeful that the new school year would be far more “normal” than the previous one.

As a mom and a researcher, I realize how difficult the 2020–2021 school year was for students, parents, and educators. As Renaissance’s new, full-year edition of the How Kids Are Performing report shows, fifth graders like my daughter ended the year 4–7 weeks behind where we would have expected in reading, and more than 12 weeks behind where we would have expected in math. On top of that, state summative assessment results from our home state of Texas showed that only 3 in 10 students met expectations in fifth grade science.

Moving forward and starting middle school is already a challenging endeavor, even without the cumulative impact of the pandemic. So, what can we learn from this past year, and what things should we keep in mind as the 2021–2022 school year gets underway? I’d like to share five key observations from both research and my own experience.

#1. This is not just a physical health crisis

Yes, COVID-19 has taken more American lives than the Civil War (which has the highest American death toll of any war in history). But the impacts are not limited to physical illness—the pandemic has also affected students’ mental health. A recent review of research found that quarantining for children and adolescents was associated with a higher likelihood of developing acute stress disorder, adjustment disorder, symptoms of grief, and even PTSD. Nearly 40 percent of students were estimated to have symptoms of psychological distress, with 35–44 percent experiencing depression and 19–37 percent experiencing anxiety. The pandemic has also worsened symptoms for students with ADHD.

The research suggests that media entertainment, reading, and physical activity—along with a better understanding of COVID-19—may protect children from negative mental health impacts.

#2. We can do a lot—but we can’t do everything

I’m a working mom, so this idea isn’t new to me. I’ve passed up chaperoning field trips, dropped off store-bought cookies for school bake sales, and driven my kids to sports practice while taking conference calls. But I have also left a conference early to be home for the first day of school, and I led a weekly elementary-school book club so my daughter could spend more time with her classmates after we moved to a new school. The question is often one of prioritization. The same was true during the pandemic.

With the introduction of virtual learning for many students, parents acquired additional roles as teachers, instrument and vocal coaches, mid-day chefs, and even tech support. While hopefully we are able to turn many of these roles back to the professionals this school year, students are still starting the year several months behind where they typically would, and we must again acknowledge that we can’t do everything. We need to prioritize learning objectives for students in the same ways that we have prioritized other aspects of our lives.

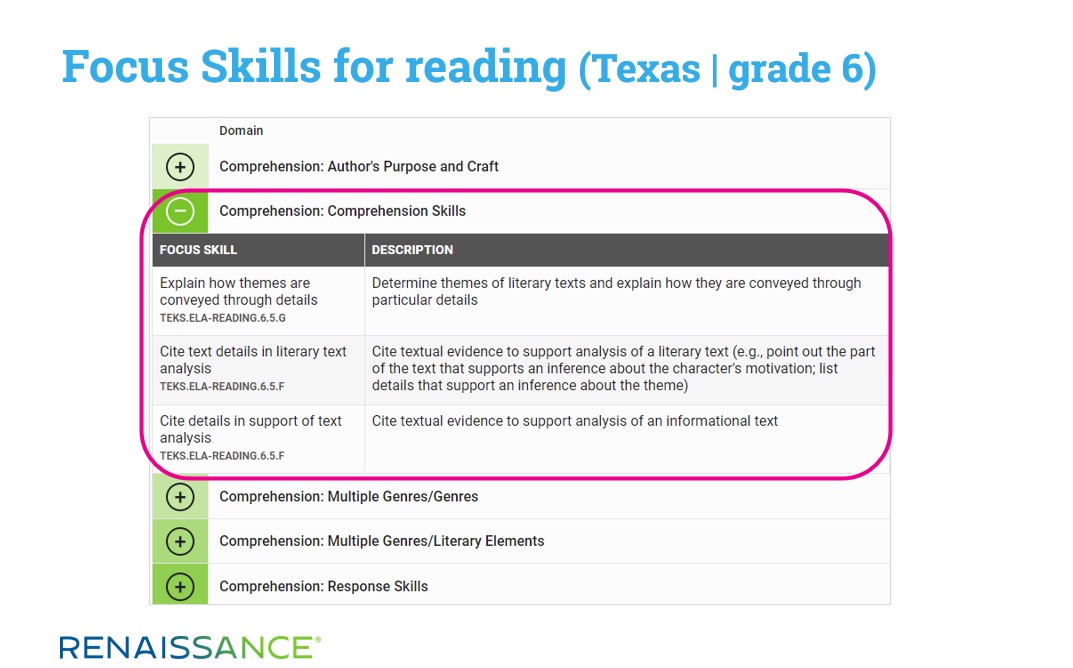

Clearly, some things are essential (e.g., food to eat), while others are nice to have (e.g., brand new clothes in the latest style). Renaissance has identified the essential reading and math skills for every state, which we call Focus Skills and which are freely available on our website. I see that for Texas sixth graders in English Language Arts, my daughter should focus on citing details from text to support and understand how text structure is linked to author’s purpose and is used to develop ideas.

Also in the Texas grade 6 ELA standards is for students to infer themes within and across texts. However, this is not identified as a Focus Skill, and I would expect it to be deprioritized given other needs this school year. Not every skill or standard can receive the same level of emphasis as we work to catch students up, and I hope that educators will have the flexibility to prioritize those standards that are most critical to students’ success at the current grade level and in preparation for the next one.

#3. A year’s growth may not be the right expectation

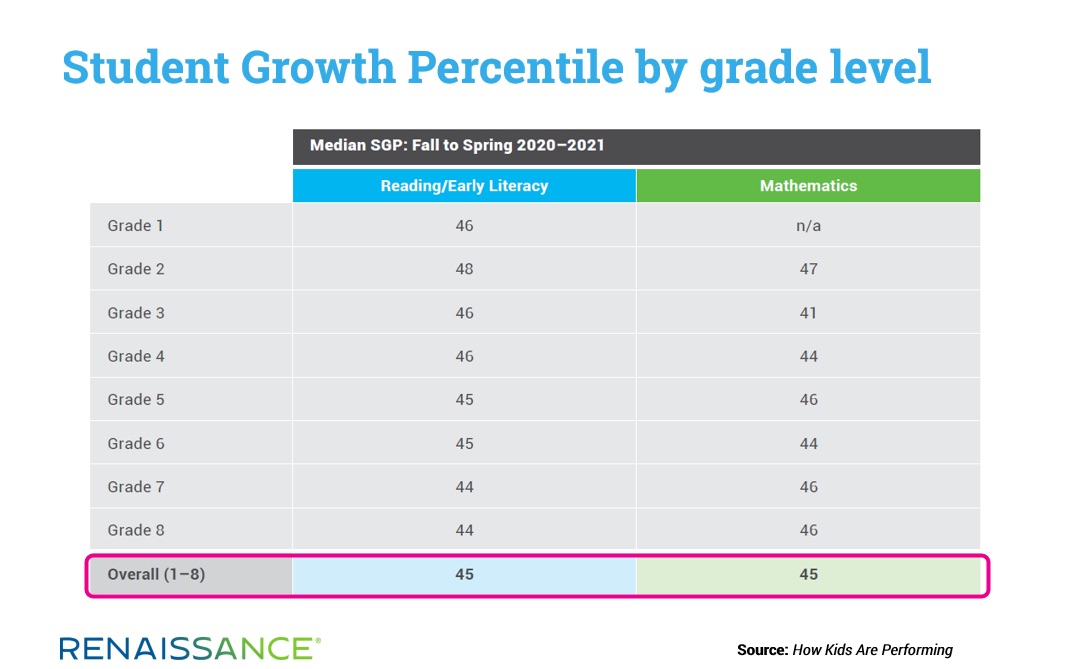

We frequently like to see that a student makes a year’s worth of growth in a year of time. However, during the pandemic, students did not grow at typical rates. In fact, compared to a typical year where students generally attain a Student Growth Percentile (SGP) of 50, students only achieved an SGP of 45 in both reading and math during the 2020–2021 school year.

With all of the disruptions and changes in learning environments, it’s not surprising that, on average, students grew more slowly than in typical years. Now that a new year has started, there are a few different types of expectations that could be set. First, given that we are still experiencing the pandemic, and students may be in changing learning environments once again, it might be reasonable to expect growth rates this year to be somewhat similar to last year—around the 45th percentile. Compound seasons of lower- than-average growth will result in students falling further behind pre-pandemic expectations, but the pandemic has clearly created extraordinary circumstances. As long as we are battling threats to both physical and mental health, perhaps having students achieve 45th percentile growth is something to applaud.

A second option might suggest that because we are now into our second full year of schooling during the pandemic, we may have implemented better strategies. More schools are opening for in-person learning, and we might be able to resume something like a typical school year, where 50th percentile growth could be expected. However, even in this scenario, students would not have caught up to pre-pandemic expectations. In fact, if students are to complete their unfinished learning from last school year in addition to the new learning expectations of this year, growth rates will need to be well above the 50th percentile. Could we reasonably expect 55th percentile growth this year, due to the influx of additional education funding and potential strategies such as increased instructional time and tutoring?

These are challenging questions, and parents and guardians should speak with their children’s teachers about determining the most appropriate goals for their children this school year.

#4. Access to educational materials is critical

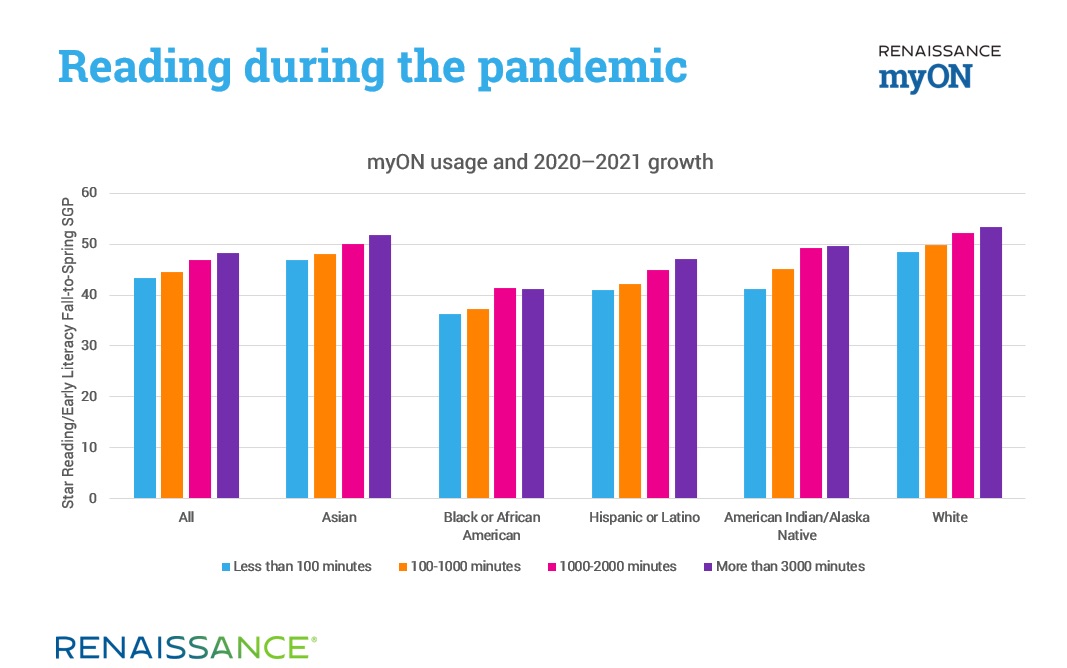

When school buildings and public libraries closed in March 2020 due to COVID-19, we had to get creative about how to get books for our children to read. Online library collections through applications such as Cloud Library and Renaissance’s myON platform were crucial for my children. Even though my youngest prefers hard copy books, she was able to adjust to online reading fairly quickly. (Incidentally, our data show that the more time students spent reading on myON last year, the greater their reading growth—a finding that holds across all racial and ethnic groups.)

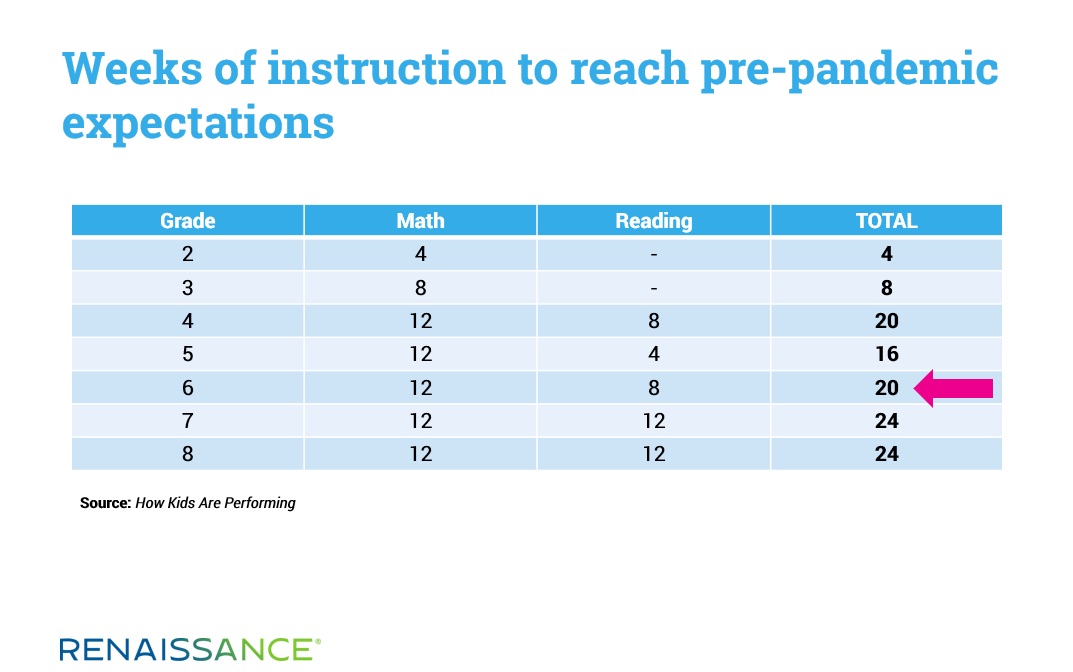

We also investigated several online math applications—including Renaissance’s Freckle program—where my kids could practice their math skills at an adaptive pace that was appropriate for each of them. It may not be realistic to think that the school will make up for the approximately 20 weeks of additional learning that incoming sixth grade students will need across both reading and math. Having my children read books and practice skills outside the classroom while we’re driving to activities or taking a road trip to see their grandparents can provide additional learning opportunities without requiring direct instructional time from their teacher (or me).

#5. Everyone’s situation is unique

It’s clear that the pandemic has not impacted everyone in the same way. Some of us were fortunate enough to have jobs where we could work remotely and choose a remote learning option for our children. Others spent little time with their children because they were working in hospitals treating the sick, while still trying to keep their families safe. We’ve seen higher COVID-19 fatality rates among Indigenous, Black, Pacific Islander, and Latino Americans—a rate almost twice as high as for whites or Asian Americans. Increased mental health risk has been associated with parental distress, financial strain, living in a high-risk COVID-19 area, and living in a rural area.

Our How Kids Are Performing report shows that the academic impacts of COVID are most significant for Black, Hispanic, American Indian, and Alaska Native students, English learners, students with disabilities, and students attending urban and Title I schools. There have been disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 in a variety of spheres, and we must have an equally disproportionate response. As students come back to school this fall—whether in-person or in remote or hybrid learning environments—administrators and teachers need to review their data and determine which schools, which content areas, and which students are most in need, and then develop plans accordingly.

Supporting teaching and learning this year

Just as I know that my daughters are unique—with different strengths and weaknesses, and in need of different supports to be successful both in school and out—our classrooms and schools are full of unique students with unique circumstances. It is our job as a community to come together around these students and schools and help support them in ways that are most conducive to students’ success— whether that be academic achievement or physical and mental health. I was really excited to be able to send my girls into a school building this year to make new friends, engage with a variety of caring teachers, and have the opportunity to participate in activities such as arts, sports, and music. However, I know this is going to be a challenging school year, and students and schools will continue to need our help and encouragement as they navigate both new and lingering COVID-19 impacts.

Learn more

Download the full-year edition of How Kids Are Performing for more insights on the most urgent needs this school year. Also, watch Dr. McClarty’s recent webinar for 3 helpful tips for accelerating learning this fall.