July 22, 2022

For me, as for so many others, the last couple of years have brought a lot of unanticipated work. When I say that, I’m referring more to the nature of the work I’ve been doing than to the quantity—although I’ve had plenty to do. As the COVID-19 pandemic dragged on, we all found that some of our projects were far less relevant than we’d initially thought. Others, perhaps considered secondary at first, became essential.

My work has revolved around three major Renaissance projects—Focus Skills, Trip Steps, and How Kids Are Performing, our ongoing analysis of how students’ performance and growth have been impacted by the disruptions. Perhaps surprisingly, working on these projects has given me new insight into what sustained progress in literacy looks like for K–12 students. It’s like climbing a sheer rock face—and then climbing a mountain.

In this blog, I’ll explain how I reached this conclusion. I’ll also explain why an understanding of these two feats will be so important this school year, given the pandemic’s ongoing effects on many students’ learning journeys.

1. Foundational literacy skills: Climbing the rock face

In the summer of 2020, Renaissance made the decision to provide all educators with free access to our Focus Skills for reading and math. Focus Skills are the most essential skills at each grade level—the skills that students must master in order to progress. Focus Skills are tailored to the learning standards of each state, and they provide powerful guidance for prioritizing our work with students.

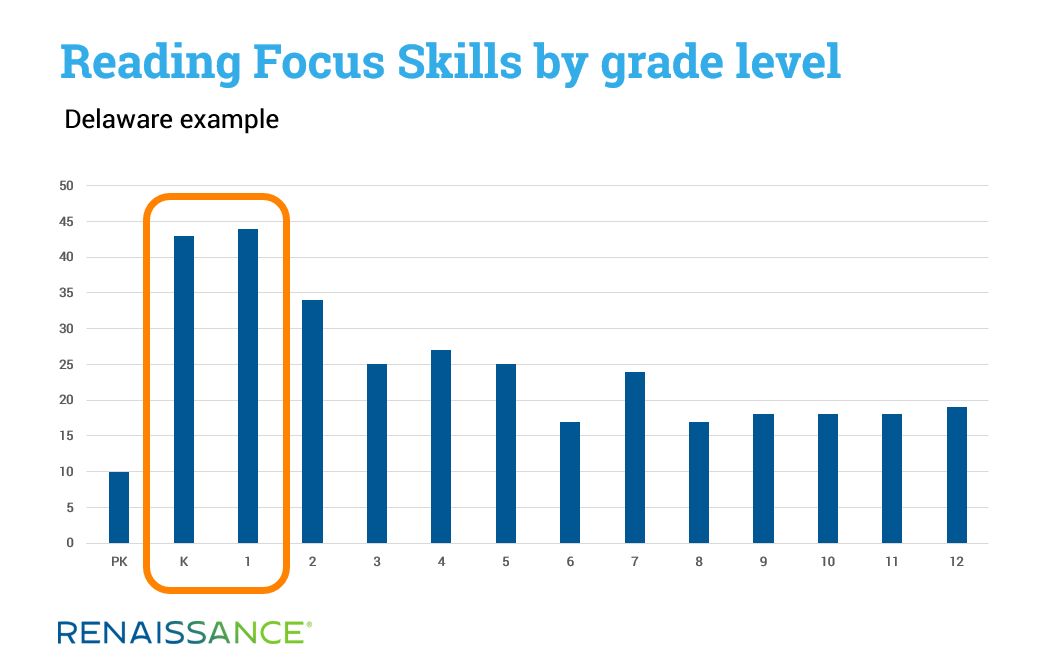

Despite some minor differences in standards across the states, Focus Skills tell a remarkably similar story, that of a sheer rock face that students must climb in relation to literacy right as their schooling begins. The following figure shows this rock face:

I’ve chosen to use Delaware as an example, but in every instance—across all 50 states and Washington DC—kindergarten and grade 1 have the highest number of reading Focus Skills. This makes sense because, at these grade levels, students are building the foundational skills that are critical for literacy development. These skills are, in other words, essential to students’ progress, which is the definition of a Focus Skill.

This rock face awaits students right as they begin their schooling. It’s as if the literacy content says to them, “Welcome to school. I hope you ate a hearty breakfast because we have a lot of work to do!” This also helps to contextualize the finding in How Kids Are Performing that students in the early grades have been disproportionately impacted by the disruptions. Missing out on even one essential skill in phonemic awareness, phonics, word recognition, and other foundational literacy domains can greatly impede students’ progress.

2. Ongoing literacy growth: Climbing the mountain

Focus Skills told us about the sheer rock face, but we learned about the second element—the mountain—from our work with Trip Steps for Reading.

Trips Steps are those Focus Skills that are also very challenging for students to learn. Our teams identified Trip Steps during the empirical validation process for our state-specific learning progressions. When we presented students with Star assessment items linked to the various skills represented in their state’s standards, we found that some skills are significantly more difficult than others. To put this another way: If learning is a staircase, then not all steps are of equal height. Some require a bit more of a climb—and these are the Trip Steps.

It may be easiest to illustrate this concept with an example from mathematics. The most challenging math Trip Step is in grade 3: Find the area of a rectangle by multiplying side lengths. If you’re familiar with the grade 3 math curriculum, you’ll understand why this is so challenging. Grade 3 students have just learned multiplication. And while they may have encountered the concept of area before, it would have been mostly through using tiles, not a formula of length times width. Then, the product of the calculation results in something else new, square units.

This is a lot of new content: a new operation (multiplication) coupled with an expanding concept (area computed via a formula) and resulting in a new unit (e.g., square inches/centimeters). To borrow a phrase from an earlier blog: new skill + new process = potential for some students to “trip.”

When we look at Trip Steps for Reading, we see that they add to the story of the sheer rock face while also telling us about “the mountain.” How so? The most challenging reading Trip Step is in kindergarten: Distinguish between similarly spelled words by identifying the sounds of the vowels that differ (e.g., pick the word that has the /a/ sound: cat, cot, cut). Phonemic awareness—which can be extraordinarily difficult for young children—is part of the rock face I mentioned earlier, meaning the large number of essential literacy skills that students encounter at the beginning of their schooling.

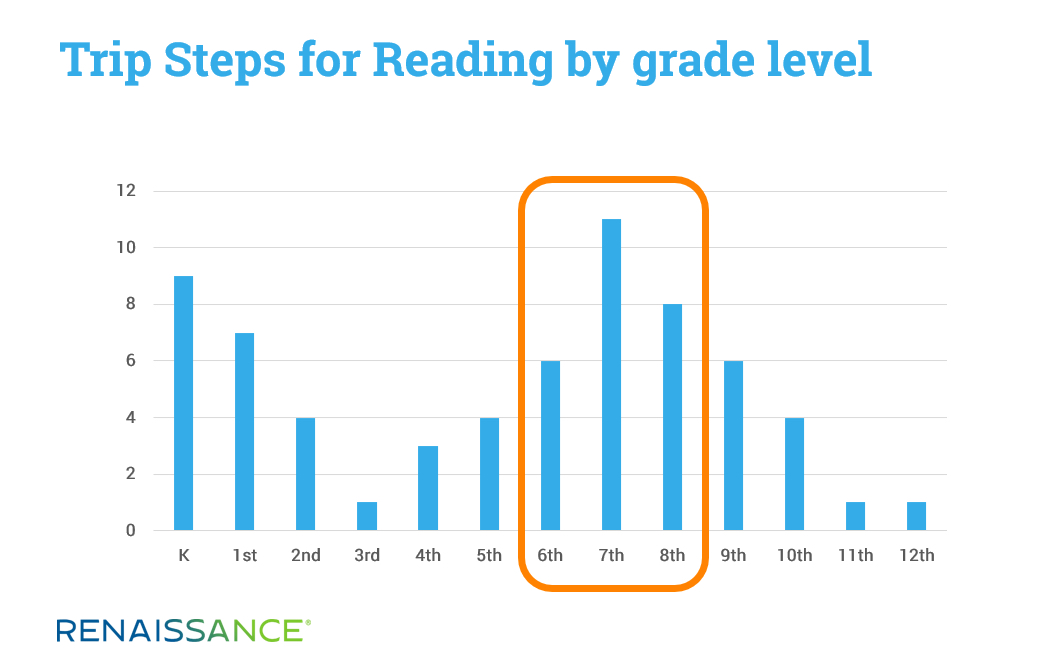

But when we look at the distribution of reading Trip Steps across the grades, the mountain emerges. In fact, students don’t reach the “peak” until grade 7, where the largest number of Trip Steps awaits them:

Armed with the knowledge of where the most disproportionately difficult content is found—in grade 7 and around it—we began to explore the Trip Steps in these grades looking for common elements. And we found two aspects of “the mountain.”

First, even a cursory review of the reading Trip Steps at this level reveals the rigor associated with them. They begin with verbs like “Analyze” or “Interpret” or “Explain.” As many of us will remember from our undergraduate days, these verbs are associated with the higher levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy or the deeper levels of Webb’s Depth of Knowledge (DOK).

The Trip Steps individually reveal this aspect of rigor, but when we look at reading Trip Steps collectively, another insight emerges with important instructional implications: They require extensive experience with text to be successful.

The most important reading standard of all

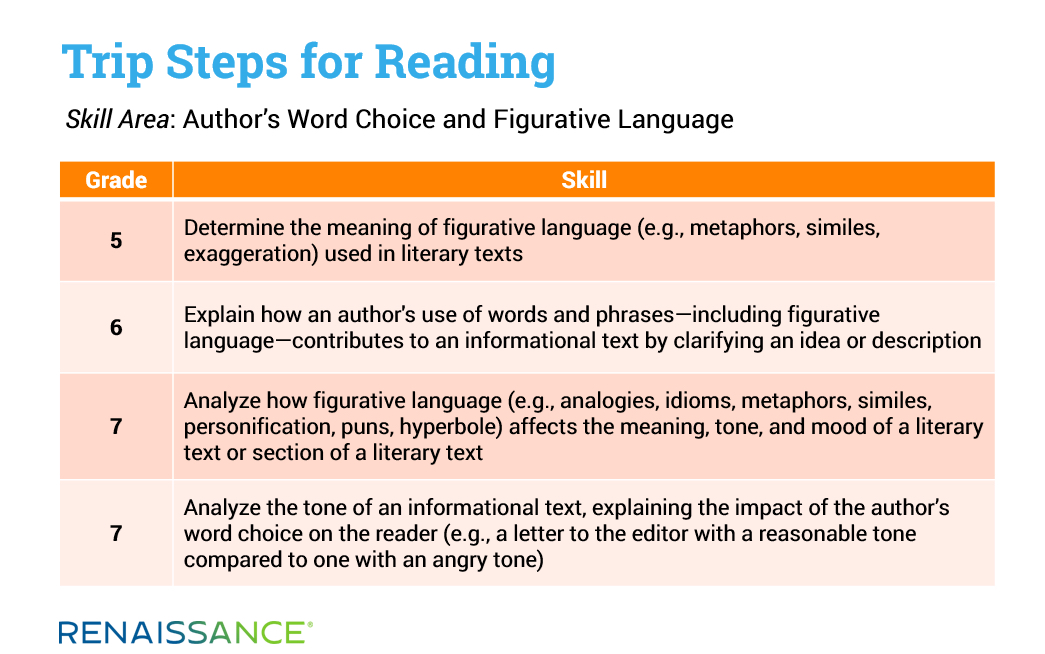

Why is this the case? Looking at the Trip Steps in and around grade 7, we see they’re generally found within the skill areas of Argumentation, Conventions and Range of Reading, and Author’s Word Choice and Figurative Language.

How can students ever be successful in the skills associated with Argumentation if they’ve read very few arguments? Similarly, being successful with the skills related to Conventions and Range of Reading requires that students have interacted with texts where they’ve seen manifestations of varying conventions, as well as applications of Author’s Word Choice and Figurative Language.

Students who have read widely are primed to learn the labels and terms for various genres (e.g., satire, parody) and those for Word Choice and Figurative Language (e.g., hyperbole, connotation, denotation). Without the text exposure and context provided through wide reading, our instruction targeting these concepts is difficult to follow. Students without wide print experience will find the ideas too abstract. They have no prior understanding or experience to which they can connect the new ideas we are presenting.

Consider a lesson where a teacher presents the concept of satire for the first time. Perhaps the teacher assigns Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal where, writing to chastise the English aristocracy, Swift satirically proposes that the famine in Ireland could be solved and poor children prevented from “being a Burthen to Their Parents or Country” if the English simply ate the poor Irish children, “making them Beneficial to the Publick.”

The astute reader quickly realizes that Swift is using a clever literary technique to shame the English for their inaction and indifference. A student who has read widely and encountered several satirical works finds both the concept and the new term easy to take in. “I’ve read things like this before. I just didn’t know what it was called.” A student with limited text experience, however, struggles to even take in the concept. “What’s this guy saying? That they should really eat the kids?”

This makes me think of Mike Schmoker’s comment that “symbolism, figurative language, setting, mood, or structure have their place but are absurdly overemphasized” in most standards sets. He adds that many of our standards “do very little to clarify the amount of reading and writing students must do to become truly literate—which may be the most important ‘standard’ of all.” In other words: We unquestionably need to teach about literary devices and techniques, but if our teaching of skills takes up so much time that students are not reading widely, then we’re creating learning dynamics that are far from optimal for progress in literacy.

How Renaissance can help—this school year and beyond

Within our literacy offerings, Renaissance has a collection of tools ideally suited for climbing both the rock face and the mountain.

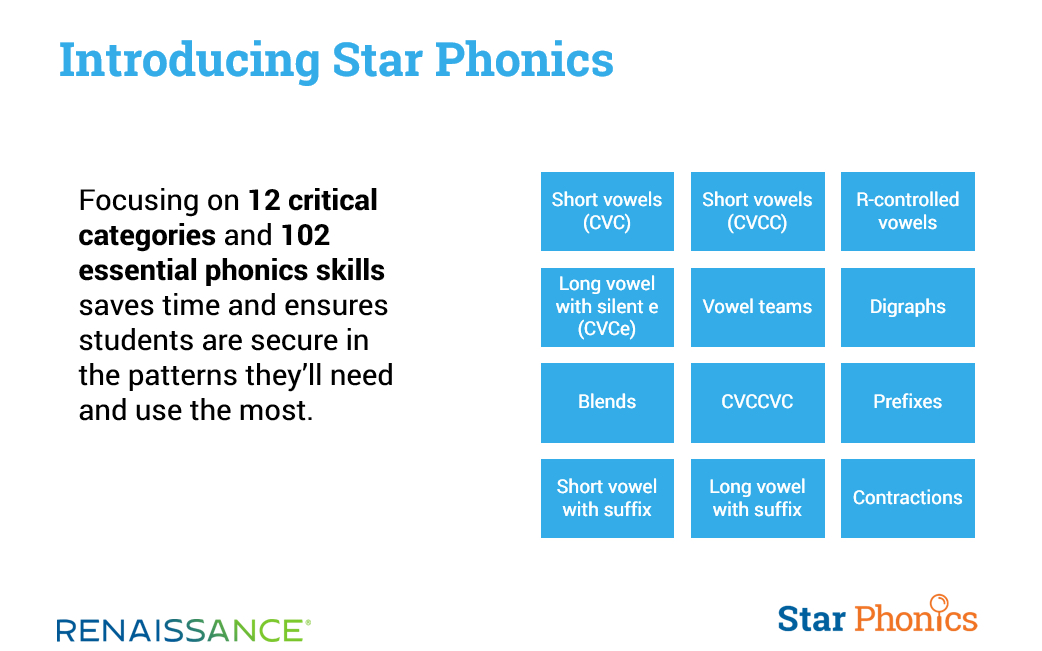

When helping students to ascend the rock face of foundational literacy skills, the critical consideration is that every student must master every essential skill to be successful. Our new Star Phonics assessment fits perfectly into this space by supporting teachers as they track students’ progress in acquiring 102 phonics skills clustered in 12 categories (shown below). Through the use of short screening and diagnostic measures, teachers are provided with detailed feedback as to which students are struggling with which specific phonics patterns. Then, our Lalilo and Freckle programs can be used to help provide the right foundational literacy practice.

Used together, Star Phonics, Lalilo, and Freckle provide powerful assistance in tracking and supporting students as they ascend the rock face. But once they’ve finished this ascent, they must then climb the mountain. This is where Accelerated Reader and the myON digital reading platform come in, to help ensure that students have easy access to text and that they’re reading with a high level of comprehension.

What we’ve learned about progress in literacy

You know the old adage: Hindsight is 20/20. If we’d known in early 2020 what we know now, we could have used Focus Skills and Trip Steps to predict where we’d see the most significant impacts on literacy development due to the pandemic. In fact, this analysis of Focus Skills and Trip Steps aligns nearly perfectly with our How Kid Are Performing studies, where we found that early grades readers and students in late middle school—the times when learners encounter either the rock face or the mountain—have been the most impacted in terms of literacy.

No mountain climber would ascend Mt. Everest without a skilled guide, and there are no better guides for that journey than the Sherpa, a Himalayan people who are renowned for their skill in mountaineering. If the journey to literacy involves ascending both a sheer rock face and a mountain, then teachers—if they fully understand the path and the possible pitfalls along it—can be students’ guides on this essential journey.

Learn more

Watch Dr. Kerns’s new webinar for more insights on the 2022–2023 school year—including why we need to rethink our assessment practices in order to best address the ongoing pandemic impacts.